Turkey’s Great Transformation: An Influence-Multiplier for the Future of Europe and Beyond

Download this article in PDF formatAbstract

In the 21st century along with the BRICS countries including Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, Turkey has acquired a stronger global position as a rising power. In terms of its economic capabilities, unique geographic position and political significance, Turkey has become one of the most dominant actors in its periphery and beyond. Turkey’s power is on the rise and there are a number of reasons for that. There are two main components behind Turkey’s rise: activism in foreign policy and strong economy. These components together with Turkey’s domestic political transformation have also reflections on Turkey’s relations with the European Union (EU). This article aims to analyze the roots of Turkey’s rising power and reflection of Turkey’s rising power on Turkey-EU relations. In this context first activism in foreign policy and strong economy will be discussed to understand Turkey’s increasing role in global politics. Then changing dynamics of Turkey-EU relations will be assessed.

Keywords

Introduction

“The world is bigger than five”, as President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan addressed several times at the United Nations (UN) General Assembly to remark five permanent members of the Security Council’s decision-making system. This clear and unambiguous statement simply underlines the fact that the global order is changing and international system should adopt itself to present-day realities which are different than 70 years ago.

The global order is being reshaped in the 21st century by the erosion of principles of sovereignty, territoriality, non-intervention, the increasing importance of democracy and human rights and more than ever the new actors such as non-governmental organizations, transnational companies, civil society organizations are shaping international politics (Parlar Dal & Oğuz Gök 2014, p. 3). Already, multiple and competing sources of power emerged around the world. The bipolar and unipolar structure of world affairs has altered by a much more complex tapestry of forces, alliances and issues (Stanley Foundation 2009).

Moreover, dynamics of globalization and end of the Cold War era have brought the systemic changes shifting the centers of power. Western world is gradually losing its attractiveness to be replaced by a new international system. As Hurrell puts it, power is shifting in global politics from the old G7 countries to new emerging powers (Hurrell 2013, p. 224). Moreover, this power shift has brought not only a change in the characteristic of economic and political power relations, but more importantly challenging the existing order of global justice on behalf of the “rest” of the world. Indeed, newly emerging actors position themselves as active players demanding the global transformation of center-periphery relations in order to create a more democratic and fair international system (Kalın 2011, p. 5).

In the 21st century along with the BRICS countries including Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, Turkey has acquired a stronger global position as a rising power (Müftüler-Baç 2014). In terms of its economic capabilities, unique geographic position and political significance, Turkey has become one of the most dominant actors in its periphery and beyond.

Turkey’s power is on the rise and there are a number of reasons for that. There are two main components behind Turkey’s rise: activism in foreign policy and strong economy. These components together with Turkey’s domestic political transformation have also reflections on Turkey’s relations with the European Union (EU).

Once on the periphery of the West, Turkey has gradually emerged as the center of its own world, which also encompasses the Middle East, the Caucasus and the Balkans and even areas further afield such as the Gulf and North Africa. After the Cold War period, in the absence of a bipolar world confrontation, Turkey has showed a great determination to work towards the emergence of a new international order thanks to Turkey’s re-awakening of its assets rooted in its history, culture and geography (Yeşiltaş 2014).

The Justice and Development Party’s (AK Party) fourteen years in power have played a big part in Turkey’s rising power. Turkey has experienced a spectacular transformation process through further democratization, improvements in freedoms, an economic restoration in tune with the global economy and an active foreign policy since 2002. AK Party brought path-breaking changes in Turkish domestic politics, such as the normalization of civil-military relations and democratization in the political sphere, as well as Turkey’s foreign policy and national security doctrine (Kanat 2013, p. 1). Within governing institutions, political parties, civil society and the private sector, Turkey mobilized a powerful coalition of actors from different walks of life who united in propelling the country towards a distinctly higher level of democracy and economic development (Independent Commission 2014, p. 6).

The great political, social and economic transformation affected the process and prospect of EU membership. In fact, as argued by many observers, the decision by the AK Party to make accession to the EU one of its major objectives, the increasing global and regional role of Turkey and the increasing importance of civil society are together making Turkish modernity more societal, liberal, plural and multi-cultural (Derviş, Emerson, Gros & Ülgen 2004, p. 16). This transformation has put an end to former asymmetric relations between Turkey and the EU and placed the relations on a more equal footing.

This article aims to analyze the roots of Turkey’s rising power and reflection of Turkey’s rising power on Turkey-EU relations. In this context first activism in foreign policy and strong economy will be discussed to understand Turkey’s increasing role in global politics. Then changing dynamics of Turkey-EU relations will be assessed.

Activism in Foreign Policy: Hard and Soft Power Clout

Leaving behind the single-dimensional and reductionist perspectives of the Cold War era, Turkey has reconsidered its strategic priorities and overcome the binary oppositions of the Cold War era. In fact, new multi-dimensional and active foreign policy doctrine is the most important asset of Turkey as a rising power. Today in every parts of the world, Turkey is fully determined to contribute to a new international order, which would be more representative of the current distribution of power capabilities across the globe (Oğuzlu 2013, p. 774). Turkey would like to put an end to global injustice, economic and social inequality, undemocratic representation and decision-making in major international institutions, and the geopolitical, geo-economic and geo-cultural marginalization of the Muslim world (Parlar Dal & Oğuz Gök 2014, p. 5).

Turkey’s foreign policy agenda is shaped in a more confident and autonomous policy stance that has upgraded Turkey’s regional economic and geopolitical position (Serbos 2013, p. 144). Turkey has been investing in its geopolitical and geocultural positions by taking a leading role in the establishment of regional organizations, making attempts to economically integrate the region, opening consulates in many countries, trying to become a hub for energy pipelines, culturally presenting itself as a role model in the region, making attempts to promote democracy in the Arab world and improving ties with the rest of the world (Yuvacı & Doğan 2012, p. 10).

Indeed, Turkey has always pursued effective multilateral cooperation, as exemplified by its membership to various international and regional organizations (Parlar Dal 2016). Turkey has been a founding member of the United Nations (UN), Council of Europe (CoE), Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) as well as Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) in 1945, 1949, 1960, 1969 and 1975 respectively. In addition, Turkey has been contributing to global peace and security as a NATO member since 1952. But particularly for the last fifteen years Turkey’s global activism has increased tremendously thanks to its growing economy and multidimensional foreign policy based on Turkey’s hard power but also especially on its rising soft power. As Falk (2013, p. 353) emphasized, “More than any country in this century, Turkey has raised its profile as a regional and global political actor”.

The UN is a significant platform where Turkey’s global activism can be clearly observed (Sever & Oğuz Gök 2016). Previously, Turkey had served as non-permanent member of the UN Security Council in 1951-52, 1954-55 and 1961. After 48 years, Turkey once again became non-permanent member of the Security Council for 2009-2011 term. It is no coincidence that this membership came at a time when Turkey was following a more active foreign policy than ever. What is more, though not elected, Turkey ran as candidate for non-permanent membership for 2015-2016 term. This is a clear proof of the fact that avoiding responsibilities is not a preference for Turkey. On the contrary, Turkey is ready and quite self-confident to take on responsibilities in order to contribute to global order, peace and security. In this framework, Turkey became one of the co-founders of Alliance of Civilizations initiative under the UN, aiming to break down prejudices between West and Muslim societies. Recently, on 3 November 2016, the election of a Turkish academic as a member of the UN International Law Commission after more than 20 years by obtaining 75 % of the votes cast is another indicator of Turkey’s increasing visibility under the UN umbrella.

Turkey, with the help of its multidimensional foreign policy drawing on its hard and soft power, has been making remarkable contributions to global peace and security especially through various operations under NATO framework. Turkey has the second largest army of NATO. In addition, according to Global Firepower Index (2016), Turkey has the 8th largest army among the 126 countries included. Turkey ranks 9th both in terms of total aircraft strength and tank strength. Among the EU candidate countries, Turkey is the only country that is also an active member of NATO. Indeed, Turkey is also actively engaged in the EU’s Security and Defense Policy through its participation in the EU’s civil and military missions held in Bosnia Herzegovina, Macedonia,

Congo, Kosovo and Palestinian Territories.

It is obvious that military might alone is not sufficient for an effective multidimensional foreign policy that would make an impact on global governance. It should be complemented with “soft power”, which was firstly defined by Joseph Nye (2004) as “the ability to shape the preferences of others.” Thanks to its geographical position, historical linkages, growing economy and proactive and multidimensional foreign policy, Turkey has been enjoying a considerable degree of soft power in its region comprising of the Balkans, Central Asia, Caucasus and Middle East. Turkey highlights the concept of “regional responsibility” in her efforts to contribute to the peace and stability of its region.

The Balkans bears a special significance for Turkey. Still being the most fragile part of Europe, it is the test case for lasting peace and stability. Turkey is a founding member of the Southeast European Cooperation Process (SEECP), which aims to deepen regional cooperation and integrate into the European and Euro-Atlantic structures. Turkey is also contributing to regional peace via trilateral consultation mechanisms, including Turkey-Bosnia Herzegovina-Serbia and Turkey-Bosnia Herzegovina-Croatia.

On the other hand, Central Asia is a significant region for Turkey as common ethnic, cultural, historical and linguistic ties are shared. These commonalities played a role in the establishment of the Cooperation Council of Turkic Speaking States (the Turkic Council) in 2009 by Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Being aware of the fact that a secure, democratic and market-economy oriented Central Asia will better serve the interests of the region and the world (Koru 2013), Turkey also intensifies cooperation with the countries in the region through a number of tools including, but not limited to, high-level strategic council mechanisms, joint economic commissions and cooperation councils.

Turkey has deep-rooted historical and cultural ties with the Caucasus region as well. Turkey is actively cooperating with the countries in the region through major energy and transport projects, such as TANAP, Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan Crude Oil Pipeline, Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum Natural Gas Pipeline and Baku-Tbilisi-Kars Railway. Trilateral meetings are held regularly between Turkey, Azerbaijan and Georgia to promote regional cooperation.

For the Middle Eastern countries, Turkey is a source of inspiration owing to its unique position as a democratic and secular state with a predominantly Muslim population (Parlar Dal & Erşen 2014, p. 262). It should be remembered that the launch of Turkey’s accession negotiations in 2005 had been celebrated in the Arab countries as if they would join the EU. Turkey is also playing an active role within the Organization of Islamıc Cooperation (OIC). The fact that a Turkish academic was elected Secretary General of OIC in 2004 through an election for the first time unlike his predecessors bears a symbolic importance, underlying Turkey’s rising self-confidence as a projector of democratic practices onto the Islamic world (Warning and Kardaş, 2011). Just as Spain became a bridge between EU and Latin America and Denmark became a bridge between EU and Scandinavia, Turkey’s EU accession could connect bridges between Europe and the Middle East by breaking down the prejudices and increasing mutual understanding. The stability of Mediterranean is dependent on the stability of the Middle East. In this sense, Turkey’s EU membership might help to decrease the lure of fundamentalism in the region (Müftüler-Baç, 2008).

Turkey’s soft power is well extended beyond its region. The dynamic and multi-faceted foreign policy of Turkey makes it seek to create positive synergies on a much wider scale than her immediate neighborhood. In this framework, various trilateral cooperation mechanisms established by Turkey mainly with the countries in the Balkans and the Caucasus extended to South Asia as in the case of Turkey-Afghanistan-Pakistan Trilateral Summits. Turkey’s opening-up strategies to Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean and the Asia-Pacific geographies and the existence of 235 Turkish diplomatic missions worldwide is the most visible outcome of Turkey’s multi-regional activism. The number of Turkish embassies in Africa increased from 12 in 2005 to 34 in 2013 as a result of Turkey’s opening to Africa which gained a momentum since 2005 (Kubicek et al., 2015). Turkey was granted observer status within the African Union in 2005. Turkey also intensifies cooperation with Asian partners. The fact that Turkey became dialogue partner with Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) in 2013 and recently, Turkey’s chairing of the 2017 SCO’s Energy Club as the first non-SCO country to do is illustrative of this fact.

Turkey rightfully takes pride in its policies that prioritize humanitarian concerns. In recent years, Turkey has become a leading actor in the field of humanitarian diplomacy. Ranking the second largest donor country in 2015 after the US, Turkey is also the world’s “most generous” humanitarian actor, in terms of the ratio of its GDP allocated for humanitarian aid (Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2016). Turkey’s contributions in the field of humanitarian assistance worldwide have gained international recognition as well. The first ever World Humanitarian Summit was hosted in İstanbul last May. The Summit provided a unique platform for the international community to discuss current challenges in the humanitarian system and initiate a set of concrete actions in order to enable countries and communities to better prepare for and respond to the needs of people who are affected by disasters and conflicts around the World.

Strong Economy

Another good reason of Turkey’s rising power would be economics. Economic strength was always crucial but has become even more important in an age of globalization (Arda 2015). Turkey has a large and growing domestic market, dynamic private sector, liberal and secure investment environment, high quality and cost-effective labor force, as well as developed infrastructure and an institutionalized economy. Thus economic cooperation and integration has been in tandem with Turkey’s policy of generating and sharing wealth.

Turkish economy has evolved through a transformation process to restore the macroeconomic stability and tackle with structural problems following the turbulent decade of 1990s. Post-2000 period has witnessed a social and economic transformation of Turkey with the vision to converge to economies of the developed world. In effect, the GDP growth not only resumed at a high level, comparable only to the growth rates of BRICS countries, but it was also accompanied by relatively low inflation rates, fiscal austerity and unforeseen levels of privatization and foreign direct investment. Bank and Karadağ (2012) refer to this new model of transformation as “Ankara Moment” since Turkey has promoted a model with elements of pluralism and democracy, growing economy, religious and cultural authenticity, and an independent foreign policy. Boosted by the inclusion of “Anatolian tigers”, Turkey had sizeable increases in production, exports and employment spreading all around the country.

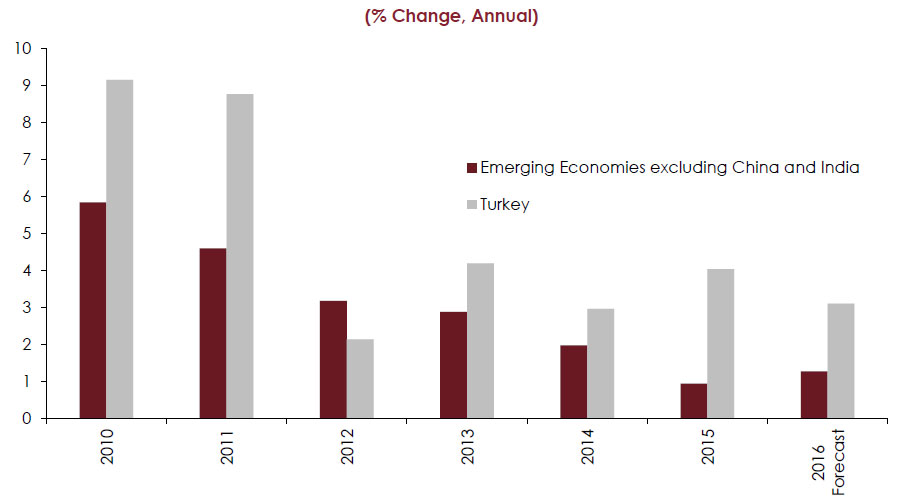

Turkey’s geopolitical position that combines the trade channels amongst the Mediterranean, the Middle East, the Asia, the Black Sea and the Caucasus regions remains the same. However, Turkey’s role as a rising economic power and a major trade actor has grown in recent years owing mostly to the structural adjustment and stability. Being the 6th largest economy in Europe and the 18th largest economy in the world, Turkey is no longer referred as a big unstable economy in the economic failures of the Middle East, but is rather positioned at the heart of the global economic powerhouse (Figure I).

Figure 1: Turkey: an emerging power?

Source: Author’s calculations, based on the data from the World Bank, World Economic Outlook Database

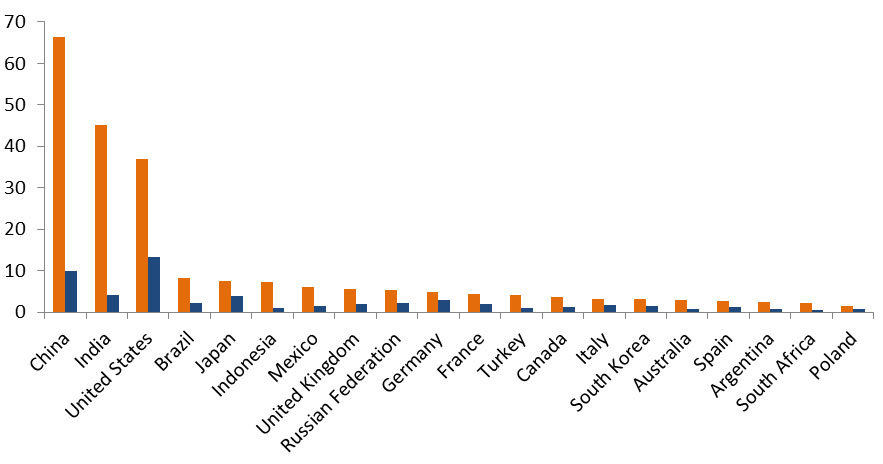

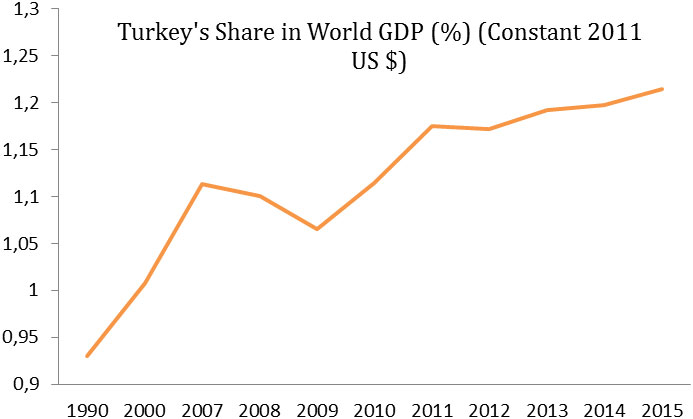

The growth rate in Turkey has outperformed emerging economies in recent years (Figure II) and Turkey became the Europe’s fastest-growing sizeable economy. Turkey’s GDP has increased from 230 billion USD in 2002 to 721 billion USD in 2015, with an average rate of 4.8 % per annum. The economic success is particularly striking at a time when EU members are muddling through financial crises.

Figure 2: Growth Rates in Turkey and Emerging Economies

(% Change, Annual)

However, macroeconomic stability and size are necessary but not sufficient conditions for an economic power with persistent prosperity. To this end, development strategies for the improvement of the physical infrastructure and research and development are being launched to boost the productivity. These strategies refer also to the priorities like environment, energy, transport, innovation, education, health and SMEs. As an economy neither endowed with rich natural resources like oil, nor having aggressive export-led strategies like the Asian tigers, the development story of Turkey may well be attributed to the “EU Convergence machine” (Gill et al., 2012). Thus, Turkey moves towards middle income to high income by applying the European economic model. Trade and direct investments being the mainstay, this economic model had paved the way for Turkey to foster innovation, productivity growth and job creation and reform finance and trade. Therefore, the restructuring goes hand in hand with the EU accession process.

With the Turkey-EU Customs Union, Turkey’s trade boomed both in quantity and quality. It is visible from the product composition of exports that the EU has made Turkish trade more sophisticated. Atiyas and Bakis (2013) and Taymaz et al. (2011) show that Turkey’s export sophistication and competitiveness have increased significantly over the last 20 years. Moreover, large and growing domestic market, mature and dynamic private sector, leading role in the region, liberal and secure investment environment, labor force, developed infrastructure, institutionalized economy and competitive tax system have become the main advantages of Turkey in attracting foreign investors. It is clear that to sustain growth, Turkey needs to deepen integration since via integration Turkey imports technology, knowledge and attracts more direct investments from the European Core.

On the other hand, one of the major strengths of Turkey lies in its young, dynamic, well-educated and multi-cultural population. There are over 25 million young, well-educated and motivated professionals in Turkey. Turkey’s future prospects are wide open in terms of demographics but better use of this asset could only be made through increasing the skilled work force, i.e. quality of human capital.

Despite the recent economic crisis in Europe, a deteriorating geopolitical environment in its neighborhood and the influx of Syrian refugees, Turkish economy seems to have proven its persistence. On the domestic front, Turkey managed to weather the storm over the challenges caused by the failed coup attempt in July 2016, making it clear that Turkey’s position as a rising power is becoming robust in the Eurasia and Middle East region (Öniş & Kutlay 2013).

As a member of G-20, Turkey possesses some differences with respect to the economies in its region. Functioning market economy rules and institutions operate reasonably well in Turkey. The most developed private sector in the region is in Turkey. Turkey is the biggest exporter in its region compared to some of the new members to the EU (like Czech Republic, Hungary, Bulgaria and Romania). Within three hours of flight, Turkey may reach a market of 1.5 billion consumers. Turkey’s close and deep economic ties with the EU and other important actors of the region provide opportunities for all.

Prospects are far from blurry. According to OECD (2012), Turkey will be the second-largest economy in Europe by 2060.

Figure 3: A comparison of 2011 GDP with OECD Forecasts for 2060

Turkey-EU Relations: Changing Dynamics

Turkey is a very different country today from what it was when it signed the Association Treaty with the European Community in 1963. Considering the fact that the world has changed, Europe has changed and Turkey has changed since 2002, the dynamics of Turkey-EU relations have also transformed. Before going through the changing dynamics in Turkey-EU relations, historical background should be overviewed.

Turkey-EU relations have deep roots emanating from a common history. European history is intertwined with the history of the Ottoman Empire, predecessor of the Republic of Turkey, through war, diplomacy, commerce or art (Tocci 2014). Sultan Mehmet II the Conqueror had Gentile Bellini, famous Italian Renaissance painter, made his portrait in 1480. A Franco-Ottoman alliance had been established in 1536 under the rule of Suleiman I the Magnificent. An alliance treaty had been signed between Ottoman Empire and Prussia in 1790. The first Ottoman Order of Crescent had been awarded to a British admiral in 1799, to Horatio Nelson, owing to his victories in the naval wars against Napoleon. It was in the Treaty of Paris in 1856 that the Europeanness of the Ottoman Empire had been confirmed.

Following the proclamation of the Republic in 1923, Turkey chose Western Europe as the model for its new secular structure. It was indeed a continuation of a trend which gained a momentum in the 19th century’s Ottoman Empire, where modernization and westernization movements had accelerated as a response to the decline of the state. In line with this policy, Turkey became member of various Western organizations. Thus Turkey’s EU membership quest is an integral part of its historical efforts for further modernization and transformation.

In 1963, Turkey signed an association agreement (Ankara Agreement) with the European Economic Community (EEC). In 1970, an additional protocol to the Ankara Agreement was signed which established the framework and conditions of the transitional stage of the association. In April 1987, Turkey submitted its formal application for full membership in the EU. With the completion of the Customs Union, the association between Turkey and the EU, in accordance with the Ankara Agreement, entered its final stage and at the European Council held in Helsinki in December 1999, Turkey was granted candidate status.

When AK Party Governments came to power in 2002, Turkey’s EU accession process has been addressed within a systematic framework for the first time and become integral to Turkey’s political vision. As Öniş puts it rightly, AK Party pursued the EU related reform agenda with a far greater degree of consistency and commitment than previous coalition government (Öniş 2006, p. 9).

The EU membership objective has been a significant motivation in accelerating the political reforms, which served to further improve the living standards of the citizens and deepened the rule of law as well as democratization. Constitutional arrangements, judicial reforms and legal amendments introduced to align with the EU acquis have helped to strengthen the Turkish democracy. The Turkish Grand National Assembly adopted eight EU Harmonization Packages between 2002 and 2004. Significant steps taken in the areas of human rights, democratization, freedom of expression and civilian oversight of the military ensured the opening of negotiations for EU membership on 3 October 2005. Since then, in Turkey’s EU accession negotiations, 16 chapters are opened whereas one chapter is temporarily closed.

Political, economic and social reforms carried out in the framework of the EU accession process have transformed Turkey, ensuring it to be a stronger actor in its region as well as in the global system. Socioeconomic transformation has gone hand in hand with democratization resulted with a growing, vibrant civil society in Turkey. People with different issues openly claim their rights as a consequence of this enormous socioeconomic change. In this sense, failed coup attempt of 15 July 2016 was a clear demonstration of the resilience of Turkish democracy.

As a result of Turkey’s grand economic and political transformation, today, the EU is facing a more and more self-confident Turkey which gives Turkey greater maneuvering room vis-a-vis Europe (Szigetvári 2014, p. 39). As Duran (2014) puts it rightly, “Turkey’s relations with the EU reflect the notion of critical integration that represents a third way between complete rejection and unquestioning obedience”. Turkey regards EU accession as a process of dialogue between equals not as parental control.

Major turning points of recent times have proved time and again the strategic importance of Turkey-EU relationship. Economic, political, security and identity related matters attest to the fact that Turkey is a key country for the EU in terms of stability and prosperity in the neighborhood. In recent years, Europe has experienced multiple and inter-related crises: The Euro crisis, the migration crisis, threat of terrorism and the Brexit. These are intimately linked to the three fundamental goals of the EU: peace, prosperity and security. Moreover, they together produced a crisis of confidence, undermining the trust of markets, citizens and global partners in the future of the EU. The scale of the challenges and the pace of events demonstrated that Turkey and the EU have to work together, to address the issues in true partnership for our common future.

Especially, the refugee crisis once more demonstrated the vitality of Turkey for the EU. The refugee crisis has severely tested the EU to its limits. In periods of crisis, most of the member states showed a tendency to go back to the basics of nationalism and protectionism and could not take a common European stance since member states were deeply divided. While EU’s response to the refugee crisis is divided and ineffective, the only point that both member states and the EU institutions agreed on is the critical role of Turkey in managing this crisis.

In this regard, following the President Erdoğan’s meetings with Donald Tusk, President of the European Council; Martin Schulz, President of the European Parliament and Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission in Brussels in October 2015; Turkey and the EU agreed to further strengthen existing ties and solidarity and adopt result-oriented action to prepare their common future. In this regard, the Turkey-EU Summit of 29 November marked a new beginning in Turkey-EU relations yielding concrete conclusions such as re-energizing accession process, fight against terrorism, accelerating of visa liberalization dialogue, burden sharing in migration management, updating customs union and high level dialogue in the areas of common interest such as economy, energy as well as international issues.

First and foremost, Turkey and the EU re-energized the accession process which constitutes the backbone of Turkey-EU relations. In this context, Chapter 17- Economic and Monetary Policy and Chapter 33- Financial and Budgetary Provisions were opened to accession negotiations. Besides, the preparatory work for the opening of the Chapters namely Chapter 15- Energy, Chapter 23- Judiciary and Fundamental Rights, Chapter 24- Justice, Freedom and Security, Chapter 26- Education and Culture and Chapter 31- Foreign, Security and Defense Policy started and has almost completed.

As another important development, Turkey and the EU decided to accelerate the visa liberalization process to lift the Schengen visa requirement for Turkish citizens. Once the visas for Turkish citizens are lifted, through increasing contacts between societies, there would be an immense positive effect in the public opinion towards Turkey’s EU membership.

Turkey has made considerable progress in a short time especially in terms of legislative alignments and operational measures stated in the Visa Liberalization Roadmap. Now the ball is at the EU’s yard to complete the process. Turkey rightfully expects the process to be completed as soon as possible and considers it as “litmus test” for the EU’s credibility.

Besides, Turkey and the EU stepped up cooperation for support of Syrians under temporary protection and for migration management to address the crisis created by the situation in Syria. Turkey’s game changer proposal of “one for one scheme” has been “a silver bullet” for managing the crisis which was agreed on Turkey-EU Summit of 18 March 2016.

According to the scheme, all new irregular migrants crossing from Turkey into Greek islands will be returned to Turkey and for every Syrian being returned to Turkey from Greek islands, another Syrian will be resettled from Turkey to the EU. This scheme is designed to break the business model of the smugglers and to end irregular migration. The scheme took effect on 20 March 2016 and the implementation has started on 4 April 2016. The figure dropped from 7000 in October 2015 to 104 in September 2016. The numbers demonstrate the success of the “one for one scheme”.

Moreover, Turkey and the EU improved their dialogue channels both in terms of quality and quantity. In a short period of time, three Turkey-EU Summits were held, where all Member States took place. Besides, High Level Political Dialogue, High Level Economic Dialogue, High Level Energy Dialogue and Turkey-EU Counter Terrorism Dialogue meetings were held to explore the vast potential of Turkey-EU relations in the fields of common interest.

Last year’s momentum in the relations is welcomed by Turkey but EU should not wait for crises to erupt in order to accelerate Turkey’s accession process. Crises bring new opportunities with themselves that should be exploited but giving momentum to the accession process only in times of crises is indeed damaging the existing effective cooperation and diminishes mutual trust.

Turkey’s European friends should understand that the futures of Turkey and the EU cannot be separated from each other. Referring to anachronistic clichés with respect to Turkey should not be an option. Instead, the EU should accommodate itself with the new reality that Turkey is a rising power of the 21st century and that it is not anymore what it was fifteen years ago.

Sharing a common future, with the same interests and the same desire for peace, democracy, stability and adherence to common values, full membership of Turkey in the EU is a win-win case. As Demiralp (2003, p. 7) argues, “Turkey’s position at the hub of vital political, economic and infrastructural networks for the EU and its uniqueness as a country embodying the values of western and eastern civilizations not only by passively bridging but belonging to two worlds, would be in full harmony with the mission that the EU should define for itself for the next decades, that is, becoming a global actor and a center of attraction via openness and reconciliation”.

Conclusion

The global landscape has changed tremendously in the recent years with the emergence of new powers, including Turkey. Turkey’s geostrategic position at a critical juncture, considerable military might, growing economic power, increasing aid flows to developing countries as well as rising commercial links coupled with a determined government resulted in a more active and respected Turkey in the multilateral fora. Therefore, Turkey’s visibility increased to a considerable extent. With the accession of Turkey to the EU, the Union’s hard power and soft power will also be strengthened, which will consequently contribute to the Union’s standing on the global arena.

Nevertheless, Turkey’s accession process is delayed due to “outdated Turkey” perceptions, which does not reflect the realities of today. Turkey is no more a poor country knocking the door of the EU. Unlike its isolationist stance in the past, Turkey now strives to reach everywhere with its assets providing the necessary credentials, including its growing economy, robust democracy as well as geographical or historical linkages (Oğuzlu & Parlar Dal 2013).

Thanks to the fact that Turkey does not have a colonial past, it receives a warm welcome in Africa. Thanks to its unique structure blending secular democracy with a Muslim tradition, Turkey is a source of inspiration in the Middle East. Thanks to its historical affinities and responsible policies, Turkey’s visibility has increased in the Balkans, Caucasus and Central Asia in a number of areas ranging from energy to culture. Turkey’s robust relations with other emerging powers including its strategic relationship with Russia are other indications of Turkey’s quest for a bigger say in an increasingly multipolar world.

Turkey’s global activism attests to the fact that Turkey has emerged as a new actor in the international politics. It does not mean that Turkey is drifting away from West as some commentators argue. Turkey has always been a part of the European family, drawing from a common history with Europe. There is a comprehensive level of cooperation ongoing between Turkey and the EU in many areas ranging from counter terrorism to energy, from commercial relations to tourism.

Indeed, today, the potential benefits of Turkish accession have become large and significant more than ever. Since the very early days of the Syrian crisis and more obviously from March 2016, Turkey has been the “life-saver” of the EU when stability, security and prosperity of the EU have been shaken by the migrant crisis. Thus it is only Turkey and the EU together that have the weight to influence the big picture. Contributions that Turkey and the EU could make to one another on a wide scale ranging from economics to politics, from culture to foreign policy are significant not only for the two, but also for regional and global peace, stability and prosperity.

Europe’s founding fathers were convinced that their countries had first to define their common interests and shared perspectives if they were to overcome their culture of conflicts and mistrust. They made no reference in those days to religious beliefs or cultural notions, not least because the European project’s motto, and its genuine ideal, was to make “unity in diversity” a reality. Today, it is looking more like a challenge. The first step towards meeting that challenge is arguably that the EU should reassess its handling of the accession talks with Turkey and adopt a firm but fair approach that demonstrates the Union is still capable of constructing a wider vision for Europe and for the world.

References

Arda, M. E. (2015), “Turkey – the evolving interface of international relations and domestic politics”, South African Journal of International Affairs, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 203-226

Atiyas, İ. and Bakis, O. (2013), Structural Change and Industrial Policy in Turkey, REF Working Paper No 2013-3.

Bakır, C. and Öniş, Z. (2010), The Regulatory State and Turkish Banking Reforms in the Age of Post-Washington Consensus, Development and Change, 41(1): 77–106.

Bank, A. and Karadag, R. (2012), The Political Economy of Regional Power: Turkey under the AKP, GIGA Working Papers WP 204/2012.

Demiralp, O. (2003), The Added Value of Turkish Membership to European Foreign Policy, Turkish Policy Quarterly, Vol. 2 No. 4, pp. 1-7.

Derviş K., Emerson M., Gros D. and Ülgen S. (2004), The European Transformation of Modern Turkey, Centre for European Policy Studies.

Duran, B. (2014), Critical Integration into the EU, SETA, http://setav.org/en/critical-integration-into-the-eu/opinion/18014, Last Visited: 2 November 2016.

Falk, R. (2013), Turkey’s New Multilateralism: A Positive Diplomacy for the Twenty-First Century, Global Governance, Vol. 19, pp. 353-376.

Gill, I. et al (2012), Golden growth: Restoring the lustre of European economic model, World Bank.

Global Firepower (2014), Tank Strength by Country, http://www.globalfirepower.com/armor-tanks-total.asp.

Global Firepower (2015), Total Aircraft Inventory Strength by Country, http://www.globalfirepower.com/aircraft-total.asp.

Global Firepower (2016), Countries Ranked by Military Strength, http://www.globalfirepower.com/countries-listing.asp.

Global Humanitarian Assistance Report (2016), http://www.globalhumanitarianassistance.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/GHA-report-2016-full-report.pdf.

Hurrell, A. (2013), Power Transitions, Emerging Powers, and the Shifting Terrain of the Middle Ground ,in Ethical Reasoning in International Affairs edited by Cornelia Navari, Palgrave Macmillan, pp 222-245.

Independent Commission (2014), Turkey in Europe the Imperative for Change.

Kalın, İ. (2011) Soft Power and Public Diplomacy in Turkey, Perceptions, Autumn 2011 pp.5-23

Kanat, K. (2013), Drivers of Foreign Policy Change in the AK Party Decade, SETAV Perspective, May 2013, pp. 1-5.

Koru, N. (2013), A General Look at Asia and Turkey’s Priorities, Türkmeneli İşbirliği ve Kültür Vakfı Avrasya İncelemeleri Merkezi.

Kubicek, P., Dal, E. P. And Oğuzlu, H. T. (eds) (2015), Turkey’s Rise as an Emerging Power, Routledge.

Müftüler-Baç, M. (2008), The European Union’s Accession Negotiations with Turkey from a Foreign Policy Perspective, Journal Of European Integration Vol. 30, Iss. 1.

Müftüler-Baç, M. (2014), Turkey as an Emerging Power: An analysis of its Role in Global and Regional Security Governance Constellations, EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2014/52.

Nye, J. (1990), Soft Power, Foreign Policy, No. 80.

OECD (2012), Looking to 2060: Long-term global growth prospect, The OECD Economic Policy Paper Series, No. 3.

Oğuzlu, T. (2013), “Making Sense of Turkey’s Rising Power Status: What Does Turkey’s Approach Within NATO Tell Us?”, Turkish Studies, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 774–796.

Oğuzlu, T. and Parlar Dal, E. (2013), “Decoding Turkey’s Rise: An Introduction”, Turkish Studies, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 617-636

Öniş, Z. (2006), Globalization and Party Transformation: Turkey’s Justice and Development Party in Perspective, in P.Burnell (ed.) Globalising Democracy: Party Politics in emerging Democracies , Warwick Studies on Globalization.

Öniş, Z. and F. Şenses (2009), Chapter 1: The New Phase of Neo-liberal Restructuring in Turkey: an Overview, and Chapter 15: Towards a Synthesis and the Challenges Ahead in Öniş and Şenses (eds.), Turkey and the Global Economy.

Öniş Z, and İ. E. Bayram (2008), Temporary Star or Emerging Tiger? The Recent Economic Performance of Turkey in a Global Setting, in New Perspectives on Turkey, No. 39 (Fall 2008), p. 47-84.

Öniş, Z. and Kutlay, M., (2013), “Rising Powers in a Changing Global Order: the political economy of Turkey in the age of BRICS”, Third World Quarterly, Vol. 34, No. 8, pp. 1409-1426

Parlar Dal, E. and Oğuz Gök, G., (2014), Locating Turkey as a ‘Rising Power’ in the Changing International Order: An Introduction, Perceptions Journal of International Affairs, Winter 2014, Vol. 109, No. 4, pp. 1-19.

Parlar Dal, E., (2016), “Conceptualising and testing the ‘emerging regional power’ of Turkey in the shifting international order”, Third World Quarterly, Vol. 37, No. 8, pp. 1425-1453

Parlar Dal, E. and Erşen, E. (2014), “Reassessing the “Turkish Model” in the Post-Cold War Era: A Role Theory Perspective”, Turkish Studies, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 258-282

Serbos, S. (2013), A More “Virtual” Turkey? Globalization, Europe, and The Quest For a Multi-Track Foreign Policy, Turkish Policy Quarterly, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 137-147.

Sever, A. and Oğuz Gök, G. (2016), “The UN factor in the “regional power role” and the Turkish case in the 2000s”, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, [online], pp. 1-36

Stanley Foundation, Rising Powers, (2009), http://risingpowers.stanleyfoundation.org/crosscuttingthemes.cfm?crosscuttingthemeid=5.

Szigetvári, T. (2014), EU-Turkey Relations: Changing Approaches, Romanian Journal of European Affairs, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 34-48.

Taymaz, E., Voyvoda, E. and Yılmaz, K. (2011), Uluslararası Üretim Zincirlerinde Dönüşüm ve Türkiye’nin Konumu, Ekonomik Araştırma Forumu Çalışma Raporları Serisi Yayın No: EAF-RP/11–01.

Tocci, N. (2014), Turkey and the European Union: A Journey in the Unknown, Center on the United States and Europe at Brookings, Policy Paper No. 5.

Warning, M. and Kardaş, T. (2011), The Impact of Changing Islamic Identity on Turkey’s New Foreign Policy, Alternatives Turkish Journal of International Relations, Vol. 10, No. 2-3.

Yeşiltaş, M. (2014), “Turkey’s Quest for a “New International Order”: The Discourse of Civilization and the Politics of Restoration”, Perceptions, Vol. 19, No. 4, pp. 43-76

Yuvacı, A. And Doğan, S. (2012), Geopolitics, Geo-culture and Turkish Foreign Policy, Geopolitics in the 21st Century, December 2012, pp. 9-23.