Rising Donors in a Transitional World: Challenges and Opportunities for Brazilian Technical Cooperation

Download this article in PDF formatAbstract

How can a transitional multipolar world affect the rise of new actors in the area of International Development Cooperation? In this article, we analyze the evolution of Brazilian Technical Cooperation projects over the last 20 years. This period was characterized by a sharp increase in the amount of money spent on such policies, which in turn made Brazil an emerging donor and prompted research on the motives that drove this foreign policy strategy. However, the literature has still neglected to combine the changes that occurred in the international arena with changes that occurred in Brazilian domestic politics, to examine if Brazil chases international ambitions. To fill this gap, we gathered unpublished data on the expenditures of all bilateral and multilateral Brazilian Technical Cooperation projects from the last two decades. Our findings suggest that the increase in Technical Cooperation in this period was directed toward allied countries. We believe that this indicates that, despite the humanistic rhetoric, Brazilian Technical Cooperation projects played a major role in advancing Brazilian interests for gathering support in the international arena.

Keywords

“All these efforts at the multilateral level are complemented by my country’s solidarity actions towards poorer nations, especially in Africa”

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva,

United Nations General Assembly, 2008“Contrary to what has been spread among us, modern Africa does not ask for compassion, but expects an effective economic, technological and investment exchange”

Jose Serra

on his takeover as Minister of Foreign Affairs, 2016

Introduction

Few things have remained the same in the international arena since Francis Fukuyama announced the “End of History” (2006) a quarter of century ago. The distribution of power is nowadays quite different than it used to be and even if it is true that the United States will remain a major player in world, the 21st century has shown that it will not be the only such power. Therefore, while the world transitions to an order in which power is much more widely distributed, rising powers will be challenged with the possibility of assuming more leadership roles in areas where previously they had no voice.

In recent years, International Development Cooperation has undergone fundamental changes. The emergence of new actors that have progressively defied the traditional approach to development cooperation, historically pursued by members of the OECD, is particularly noteworthy (Quadir, 2013; Six, 2009). For instance, countries such as India, Turkey and Brazil have become important players in this arena1 (Souza, 2012; Renzio & Seifert, 2014). Among these new players, Brazil has taken an active role in both bilateral and multilateral initiatives. The country’s International Development Cooperation strategy since 2003 has drastically changed, with a significant increase in the number of agreements signed with developing countries under the umbrella of South-South cooperation (Puente, 2010; Oliveira & Onuki, 2012). There still remains the question, however, of whether this policy was designed to increase Brazilian soft power or if it was planned with only humanitarian purposes in mind. Moreover, will this policy be maintained due to the current economic and political crises and the foreign policy preferences of the current administration?

Taking this scenario into account, the objective of this article is to analyze the evolution of Brazilian International Technical Cooperation policies since the beginning of the 2000s up to today, and examine if this policy targeted like-minded countries to boost Brazilian soft power in international organizations. To achieve this, we will follow three different but complementary strategies. First, we examine how the institutional arrangements of Brazilian International Technical Cooperation have evolved since their inception in the 1950s until the creation of the Brazilian Agency for Cooperation (ABC), the main institution responsible for the management of Brazilian Technical Cooperation. Secondly, we then analyze how Brazil has justified its International Technical Cooperation actions, placing greater emphasis on the change of discourse that took place under different ruling parties in Brazil, and on the changes that occurred in the world order. Thirdly, we present unpublished data granted to us by the ABC that describes Brazilian technical expenditures, considering whether they were channeled to bilateral or multilateral projects.

In accordance with these strategies, in the next sections, we analyze the challenges and opportunities faced by Brazil in providing technical cooperation. Based on the official rhetoric of South-South solidarity regarding these policies, we operationalize the opportunities concept as the support of the recipient countries for Brazil in governance issues of International Organizations (IOs). More specifically, we will analyze Brazilian support in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), the Executive Boards of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, and in the coalitions formed in the World Trade Organization (WTO). We operationalize the challenges concept as the economic constraints experienced by Brazil, utilizing some economic indicators, such as Brazilian GNP.

Our results suggest that, particularly between 2008 and 2012, Brazil assumed an active role as a cooperative player; a moment in which politicians and scholars claimed that the country had became a global player in the area. In this context, we argue that the Brazilian government engaged in these activities, through the rhetoric of South-South alliances, in order to look for opportunities to raise Brazil’s international profile in the international arena. Accordingly, our results suggest that this increase in technical cooperation was directed toward allied countries in International Organizations, especially in IOs such as the United Nations and the International Monetary Fund. Nevertheless, despite increasing engagement in international cooperation initiatives, Brazilian foreign technical cooperation strategy, either bilateral or multilateral, has been strongly influenced by the local economic and political situation ever since. Specifically, we found that the worsening economic situation was followed by a decrease in the provision of technical cooperation. Therefore, we discuss how the combination of economic and political crises might change Brazilian foreign policy priorities, and discuss findings that are generalizable to other rising powers under the same conditions.

Brazilian International Technical Cooperation

Over the last fifteen years Brazil has become an important player in the field of International Development Cooperation. Although the country still receives technical and financial assistance, it has come to be an active donor, leading bilateral and multilateral initiatives in International Technical Cooperation.2 The background for this change was a moment of economic growth and political stability, which allowed the Brazilian government to carry out a reorientation of foreign policy. Since 2003, through the promotion of alliances and agreements with partners from the Global South, Brazil has made several efforts to reduce the asymmetries between developing and developed countries (Oliveira & Onuki, 2012; Pinheiro & Gaio, 2014). Although International Technical Cooperation gained greater emphasis and became, with increasing clarity, an instrument of Brazilian foreign policy strategy since Lula’s first administration, these strategies have a longstanding past, which deserves to be analyzed.

The first initiative that tried to establish a coherent “International Technical Cooperation System” took place in 1950, with the creation of the National Technical Assistance Commission (CNAT). This institution was composed of government representatives from the Secretariat of Planning, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and other ministries, while its main purpose was to establish the priorities for requesting technical assistance from abroad. Multilateral agencies were not common during this period, and so technical assistance was mainly provided by industrialized countries with which Brazil had specific technology transfer agreements in the form of cooperation (ABC, 2016).

Years later, broad institutional reform was carried out in 1969, centralizing by decree the basic skills of international technical cooperation (external negotiation, planning, coordination, promotion and follow-up) in the Secretariat of Planning (SEPLAN) and in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MRE). However, the need for a new reform of the international aid management mechanisms was again outlined during 1984. At that moment, the Technical Cooperation System was under double command: the Technical Cooperation Division of Itamaraty and the Sub-Secretariat for International Economic and Technical Cooperation (SUBIN). In practical terms, while the former oversaw the political aspects of technical cooperation, the latter performed technical functions such as the proposal, analysis, approval and monitoring of projects (ABC, 2016).

In order to resolve the tensions created by this dual command structure, the Brazilian Cooperation Agency (ABC) was created on September 1987 from the merger of the two former units of the Alexandre de Gusmão Foundation (FUNAG), linked to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MRE). The creation of ABC took place at a time of great changes in the flow of international development cooperation, which materialized in Brazil in two ways.

Initially, in the context of Brazil’s technical cooperation relations with the multilateral system, a new management model of multilateral cooperation was introduced by the end of the 1980s. This put focus on a novel way of organization, which called for the control by developing countries of technical cooperation programs implemented by international organizations. It is important to emphasize that, until this point, the so-called ‘Direct Execution’ management model held sway. Under Direct Execution, international organizations were responsible for both the administrative and financial management and the technical conduction of the projects in the beneficiary countries3 (ABC, 2016).

A second strand of Brazilian foreign policy, known as South-South technical cooperation, allowed for the expansion of ABC. Having been originally created to act as the axis of Brazilian South-South cooperation, the operational structure of the agency and the composition of its human resources and management systems framework was progressively structured along the lines of the dramatic growth of Brazil’s horizontal cooperation programs, which were expanded in terms of partner countries served, projects implemented and resources effectively disbursed (ABC, 2016).

Thus, nowadays the institutional arrangements for the provision of technical cooperation are centered on ABC, which acts as an official body under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Since its creation, ABC has assumed several roles, including planning, coordinating, negotiating, approving, executing, monitoring and evaluating cooperative initiatives at the national level, as well as being in charge of projects between Brazil and developing countries, including related actions in the field of training for the management of technical cooperation and dissemination of information (ABC, 2016). In other words, ABC has the role of negotiating, promoting and monitoring Brazilian cooperative projects and programs as a whole, although this does not impede the other 170 federal government agencies that participate in this process, including ministries, municipalities, foundations and public enterprises over a wide range of areas (Ipea, 2013). Technical Cooperation is delineated by strong fragmentation and institutional dispersion, justified in part by the lack of specific legislation in Brazil that clearly defines the objectives, scope, mechanisms, competencies and processes of development cooperation (Costa Leite et al., 2014).

To conclude, changes in Brazilian technical cooperation strategy have been influenced by three major trends: (a) how cooperation was conceptualized and implemented by multilateral agencies; (b) institutional changes at the domestic level; and (c) the interaction among the international and domestic level which lead to a change of discourse, to which we pay more attention in the following section.

Why Does Brazil Engage in International Technical Cooperation? A Discursive Approach

More than a simple exchange of expertise or financial support, international cooperation can be used as a rhetorical asset. In this regard, between 2003 and 2016 Brazil sought to distance itself from the concept of foreign aid used by the Development Assistance Committee of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD/DAC), and named its foreign aid policy as Brazilian Cooperation for International Development (COBRADI).

In addition to this rebranding, Brazil started to reject terminologies such as “donor”, “aid” and “assistance”, in its public announcements.4 Instead of these terms, the country started to adopt the definition given by the United Nations Confederation on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) for cooperation as processes, institutions and agreements designed to promote political, economic and technical cooperation among developing countries that seek common development in a horizontal relationship (Milani & Carvalho, 2013). This movement was embedded in the idea that the South-to-South relationship is a more equal collaboration, as both countries are trying to develop themselves, and as such they are not interested in taking advantages of the other.

Moreover, Brazilian International Development Cooperation programs have several dimensions, such as Technical Cooperation, Humanitarian Cooperation, Educational Cooperation, Financial Cooperation, Scientific and Technological Cooperation and Peacekeeping Operations. Notable among these modalities is Technical Cooperation, which promotes training and transfer of knowledge in areas that Brazil has been successful, such as tropical agriculture and the fight against HIV/AIDS for example.

According to the Brazilian Cooperation Agency, the Technical Cooperation actions constitute an instrument of foreign policy, which Brazil has used to ensure its presence in countries and regions of interest. Nonetheless, more than one instrument was used to achieve such an end, namely: consultancies, training, and the eventual donation of equipment.

In this aspect, some authors claim that technical cooperation is beneficial to Brazil’s image in different ways. It helps Brazil to build on its soft power (Puente 2010); and strengthens its identity as the champion of developing nations (Dauvergne & Farias 2012). In addition to these symbolic aims, some Brazilian diplomats and policymakers argue that technical cooperation can foster relations in other domains with developing countries, creating favorable conditions for the achievement of economic goals abroad (Cervo 1994; Milani & Carvalho, 2013; Pino & Leite 2009; Puente 2010; Filho 2007) and the gathering of international support for raising Brazil’s international profile in international institutions (Apolinário Júnior, 2016; Hirst, Lima & Pinheiro, 2010).

Costa Leite et al. (2014) point out that Brazilian identity as a technical cooperation actor is also a product of the interplay between Brazil’s foreign policy agenda and domestic politics. In this regard, the re-emergence of South-South cooperation for development in the 2000s has to be understood within the realm of state activism in the post-neoliberal setting, especially after the 2008 financial crisis (Hirst 2011; Leite 2012). Such shifts, which coincided with the Workers’ Party (PT) coming to power in Brazil, contributed to these narratives of global distributive social justice and “solidarity diplomacy” (Faria & Paradis, 2013; Pino 2012).

In this sense, Faria and Paradis (2013) argue that the explanation for the ‘solidarity’ character of Brazil’s international integration strategy, adopted after President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s inauguration, can be explained by domestic, regional and systemic factors. The domestic motives lie in the guidelines of the Workers’ Party (PT), in the economic growth experienced during that period and in the success of domestic social policies that could be exported to other countries. The regional factors lie in the need to pay the costs of regional leadership, a long-standing goal of Brazilian foreign policy. Finally, the systemic motives are the opportunities arising from the US policy of War on Terror, the emergence of the BRICS as a political coalition, and the 2008 financial crisis.

Since 2004, the technical cooperation agreements signed by Brazil, in the context of the General Coordination of Technical Cooperation among Developing Countries (CGPD)5, have been directed by the following guidelines. First, prioritize technical cooperation programs that favor the intensification of relations between Brazil and its developing partners, especially with countries that Brazilian foreign policy considers as having priority interest. Second, support projects that improve national development programs and the priorities of recipient countries. Third, channel CGPD efforts to projects of greater impact and influence, with a more intense multiplier effect. Fourth, favor projects with a greater range of results. Fifth, support projects with national counterparts and/or with the effective participation of partner institutions. And, finally, establish partnerships, preferably with genuinely national institutions.

Moreover, according to ABC, the CGPD concentrates its actions on prioritizing the commitments made on the official travels of the President of the Republic and the Chancellor. With regard to the regional distribution of the cooperation projects, the priorities are the South American and Central American continents, especially Haiti; Africa, the Portuguese-speaking African countries (PALOPS), and the Community of Portuguese Speaking Countries (CPLP), including East Timor in Asia. Special attention is also given to the triangular cooperation initiatives with developed countries and international organizations.

Figure 1: World Map with the Total Technical Expenditure in Bilateral Cooperation Projects

Figure elaborated by the authors. Source: ABC data.

These priorities can be visualized in Figure 1, which was created taking into account the amount of money received by Brazilian international cooperation beneficiaries between 2000 and 2016. The data corroborates the CGPD’s priorities aforementioned, as most of the budget was spent in Haiti, East Timor, African and Latin American countries. It is worth highlighting the discrepancy of the distribution of cooperative money given to different countries. Haiti received just under US$57 million, representing around 40% of the total budget spent in development cooperation during the given period.

Now that we have analyzed how Brazil has changed its foreign policy aims, as well as the modification in the official discourse and terminologies, the next section deals with the way in which technical cooperation has been implemented during the last decades.

Bilateral and Multilateral Cooperation

Depending on the partners involved, cooperation can be carried out in three different ways (Puente, 2010). First, it can happen between developed and developing countries, namely North-South Cooperation or Vertical Cooperation. Second, between two developing countries, termed Horizontal Cooperation. Finally, from a triangular process between developed and developing countries for the provision of assistance to underdeveloped countries, the so-called North-South-South or triangular cooperation.

With respect to Brazilian bilateral technical cooperation, Table 1 shows that it has been highly concentrated. The data on the top 20 recipients of bilateral projects indicate that Haiti and Mozambique have received about 50% of the total spent by Brazil on bilateral cooperation between 2000 and 2016. Moreover, after the top three recipients, all the other countries have received less than 10 million dollars, displaying a more fragmented pattern.

Table 1: Top Bilateral Recipients of Brazilian International Technical Cooperation

| Rank | Receiving Country | Total Expenditure (US $ Millions) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Haiti | 56.96 | 39.49 |

| 2 | Mozambique | 15.34 | 10.643 |

| 3 | East Timor | 10477 | 7.264 |

| 4 | Guinea-Bisau | 7.80 | 5.415 |

| 5 | Cape Verde | 4.75 | 3.296 |

| 6 | Paraguay | 4.30 | 2.987 |

| 7 | Angola | 3.63 | 2.78 |

| 8 | Guatemala | 3.48 | 2.419 |

| 9 | Peru | 3.26 | 2.2610 |

| 10 | Jamaica | 2.68 | 1.8611 |

| 11 | Uruguay | 2.47 | 1.7112 |

| 12 | El Salvador | 2.41 | 1.6713 |

| 13 | Cuba | 2.00 | 1.3914 |

| 14 | Ecuador | 1.94 | 1.3515 |

| 15 | Benin | 1.86 | 1.2916 |

| 16 | Bolivia | 1.66 | 1.1517 |

| 17 | Senegal | 1.61 | 1.1218 |

| 18 | Dominican Republic | 1.41 | 0.9819 |

| 19 | Algeria | 1.36 | 0.9420 |

| 20 | Suriname | 1.05 | 0.73 |

Table elaborated by the authors. Source: ABC data.

Even though Puente (2010) has made a clear typology of international cooperation, Brazil’s South-South cooperation (SSC) does not neatly fit into its categories. Brazilian SSC is present on all continents, either through bilateral programs and projects, or through triangular partnerships with foreign governments and international organizations. In the case of Brazilian SSC, triangular cooperation is understood as an alternative and complementary arrangement to bilateral efforts. Moreover, it can be carried out with the help of two different entities: international organizations or a third country. On the one hand, the objective of a trilateral partnership involving international organizations is to join the typical elements of Brazilian SSC with efforts to promote multilateral development agendas. On the other hand, the distinctiveness of a trilateral partnership involving third countries is the development of initiatives mainly with the additional support of developed countries that were traditional partners in bilateral cooperation with Brazil, for example Japan and Germany (ABC, 2016).

Over the past decade and in particular since 2008, there has been increasing participation of Northern partners in SSC, and they engage in several different ways (Abdenur & Fonseca, 2013). Although these configurations are not entirely a novelty, this type of arrangement seems to have expanded significantly in number and size over the past decade, with more countries (donors, pivots and recipients) taking part in trilateral configurations, with varying functions and degrees of involvement (Chaturvedi, 2012).

Despite the increasing prominence of such arrangements, there are competing definitions of what constitutes triangular cooperation. There is no international consensus on the definition of “triangular cooperation”, which may also be referred to as “trilateral cooperation”, “trilateral assistance”, “tripartite cooperation” or “tripartite agreement”. In relation to the first two concepts, trilateral and triangular cooperation, even though they are often used synonymously and interchangeably, some authors highlight an important distinction between them. Rhee (2011), for instance, suggests that triangular cooperation refers to South-South cooperation supported by a Northern country or a multilateral organization. On the other hand, trilateral cooperation refers to a North-South-South cooperation project that is carried out and financed by both sides.

According to McEwan and Mawdsley (2012), although the distinction is analytically useful, in practice these terms are used interchangeably and are related to a spectrum of institutional arrangements. More broadly, Langendorff (2012) uses the terms triangular and trilateral cooperation interchangeably to define a partnership between developed donors and emerging donors to implement development cooperation projects in beneficiary countries.

All these different definitions highlight the need for further work on building consensus on the main characteristics of triangular cooperation and to clarify how to make the most out of them and deal with its challenges (OECD, 2017). For instance, the OECD defines trilateral development cooperation as arrangements between an OECD – Development Assistance Committee (DAC) country or a multilateral institution, partnering with a “pivotal” country (or emerging power), to implement development cooperation programs in a third beneficiary country (Fordelone, 2009). In contrast, the Brazilian Cooperation Agency (ABC), in its guidelines for the Development of Bilateral and Multilateral Technical Cooperation, defines trilateral cooperation as a “modality of international technical cooperation projects in which coordination and follow-up of projects and activities are shared between the Brazilian Cooperation Agency of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the international cooperation agency or cooperating international body” (ABC 2014, p.18).

Although there is no agreed definition, the literature on triangular cooperation suggests that is widely understood that triangular or trilateral cooperation involves at least one provider of development cooperation, or an international organization, and one or more providers of South-South cooperation; the goal is to promote the sharing of knowledge and experience or to implement development co-operation projects in one or more recipient countries (OECD, 2013). In addition to these common objectives, the Northern donors have some set of interrelated reasons for engaging in triangular cooperation. First, they claim that it allows them to combine forces with the often-complementary knowhow and experience of Southern cooperation providers.

Second, Northern donors point out that triangular cooperation often generates benefits in terms of cost-effectiveness because it allows for the pooling of resources, even though it often requires more complex negotiations and bureaucratic arrangements. Third, the Northern countries frequently note that triangular cooperation gives them a chance to engage with Southern cooperation providers on issues of norms and practices of aid and cooperation in a concrete manner. Abdenur and Fonseca (2013) argue that within a context of decline in Northern aid, this engagement is a way to harness South-South cooperation in order to preserve and expand Northern influence, both within and outside the field of development cooperation.

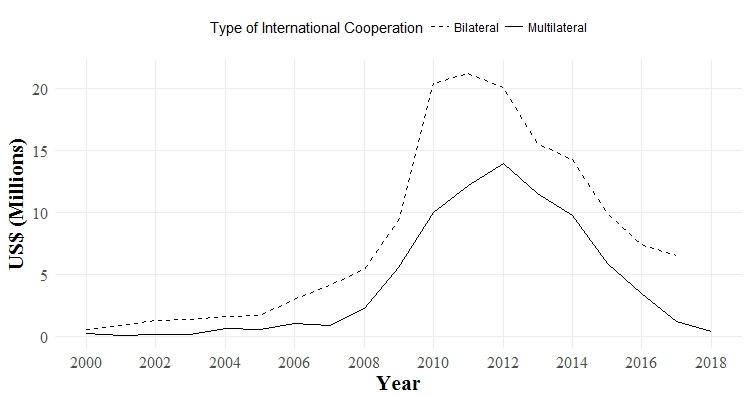

Figure 2 illustrates the difference in amount of money spent on technical international cooperation between 2000 and 2016. The units are in millions of dollars and there are two categories: bilateral cooperation and multilateral cooperation. The data on multilateral cooperation include all types of triangular cooperation and any other arrangement that is different to bilateral cooperation. It can be seen that after 2006, the total amount of money spent on technical international cooperation increased, and between 2009 and 2012, the figures jumped from about 7.5 million to an average of around 17 million. After 2012, the trend of bilateral and multilateral international cooperation follows a similar negative path.

Figure 2: Trends in International Technical Cooperation. Brazil´s Expenditure Per Year

Figure elaborated by the authors. Source: ABC data.

Accordingly, if both bilateral and multilateral cooperation seem to follow the same pattern, we should examine the causes of such a trend. We devote the next section to such an endeavor.

Looking for opportunities in the international scene

To discuss opportunities for Brazil in the international arena with regard to the provision of technical cooperation, we analyze whether this policy was guided by political-diplomatic interests. The use of foreign aid for diplomatic purposes is well documented in the literature (Lancaster, 2007). Based on McKinley & Little (1979) donor’s interest model, scholars have analyzed whether the foreign aid provided by the traditional donors was related to political support in international institutions such as the United Nations (Alesina & Dollar, 2000; Dreher, Nunnunkamp & Thiele, 2008; Kuzienko & Werker, 2006), and International Financial Institutions such as the IMF and World Bank (Vreeland, 2011). However, this relation is less clear regarding the South-South Cooperation for Development, as provided by the southern donors. Some authors suggest that these initiatives are not so different from the traditional foreign aid provided by developed countries and their Realpolitik objectives (Carmody, 2011; Souza, 2012; Prashad, 2013; Quadir, 2013; Six, 2009). Therefore, one objective of this article is to inquire as to whether Brazil, one of the major southern donors, is looking for political support to raise its profile in International Organizations.

Hypothesis 1: Brazilian technical cooperation is positively correlated with host country convergence with the Brazilian position in International Organizations.

For this hypothesis to be proven true, we would expect a positive relationship between expenditures on technical cooperation projects and the convergence of host countries with Brazil in the main IOs of the contemporary global governance structure. Specifically, we expect a positive relation between the provisions of Brazilian technical cooperation and voting convergence in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) and a positive relationship between Brazil’s technical cooperation and the political support of the recipient countries for the Brazilian Executive Director in the Bretton Woods financial institutions, namely the World Bank and the IMF. Finally, we expect that the provision of Brazilian technical cooperation was directed towards the country’s main allies in the WTO.

To test this opportunities hypothesis, we used a variable referring to the position of recipients in relation to Brazil in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) voting (Strezhnev & Voeten, 2012). We used dichotomous variables concerning the positions of these countries in relation to Brazil in international financial institutions such as the IMF and World Bank, operationalized as the (non) participation in the coalitions led by Brazil in the Executive Boards of both organizations (Apolinário Júnior 2016). Furthermore, a variable was used regarding the positions of the recipients with regard to Brazil in the coalitions within the World Trade Organization (WTO). We operationalized this variable as the ratio of participation in each of the joint coalitions with Brazil in the WTO by the total of coalitions that Brazil integrated in a year.6 Meanwhile, we expect that Brazilian technical cooperation is not correlated with economic characteristics of a country, such as the size of the population or the GDP per capita7.

Hypothesis 2: Brazilian technical cooperation is not correlated with economic characteristics of the host countries.

If Brazilian technical cooperation were correlated in such a manner, this would mean that Brazil interests are more economic than political. Moreover, if these two variables are positively correlated with the total amount spent in technical support, we would not be able to disentangle the economic interests of Brazilian technical support from the political interests.

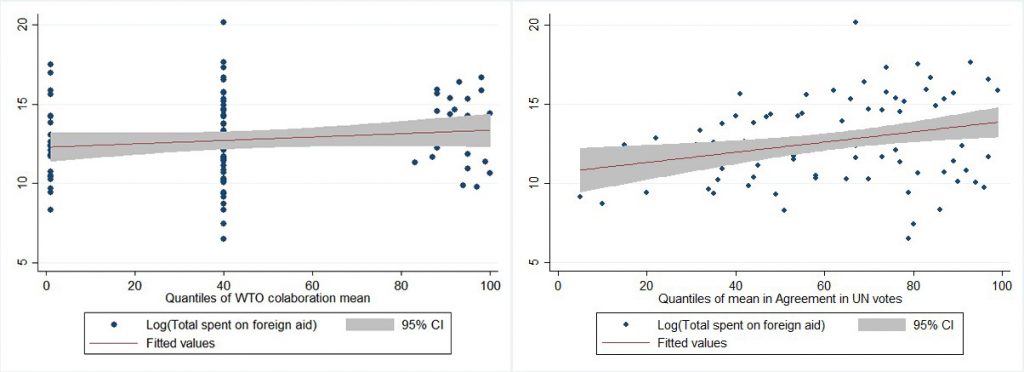

Before moving on to the statistical model, we analyze the individual relationship between these variables and the total amount spent by Brazil on technical cooperation per country. Figure 3 shows this comparison and in both cases the relationship is positive, even more for the Agreement in UN votes.8 In this regard, the greater the convergence between Brazilian and host country positions in International Organizations, the higher the amount spent by Brazil on technical cooperation projects.

Figure 3: Quantile distribution of WTO collaboration and Agreement in the UN votes on the log of total spent on Foreign Aid

The results of these preliminary tests remain statistically significant after we control for all the independents variables, as Table 2 shows. Furthermore, the model chosen to understand the determinants that influence the chance a country receives foreign aid from Brazil was a panel logistic regression. This model enables us to account for the variance across time and country, as our database has information on Brazilian foreign aid for 96 countries between 2000 and 2018.9The only drawback of the logistic model is the difficulty in interpreting its coefficients – Table 2 (1). Nonetheless, we can calculate the odds ratio of each coefficient to have a more straightforward analysis – Table 2 (2), since the interpretation can be done in odds (increase or decrease) of receiving foreign aid.[/footote]

The size of the population, a common measure of economic size, is not statistically significant for understanding if a country receives foreign aid. On the other hand, GDP per capita is significant, although its substantial impact is virtually nil – the odds of receiving foreign aid is multiplied by 1.00 for each additional dollar in GDP per capita.

In relation to the political variables Agree in UN, WTO cooperation and IMF & WB cooperation, these are all statistically significant and have a positive relation with receiving foreign aid. More specifically, for each additional point in convergence in UN votes, the country odds of receiving foreign aid are multiplied by 1327. Meanwhile, for each additional point in the ratio of participation in joint coalitions with Brazil in the WTO, the country odds of receiving foreign aid are multiplied by 96.59. Finally, the results for IMF & WB cooperation indicates that if a country switches from not participating in the coalitions led by Brazil in both IMF and WB to participating, the country odds of receiving foreign aid are multiplied by 108.27.

Table 2: Logistic Regressions on Foreign Aid

| (1) Logit Coeffs |

(2) Odds Ratio Coeffs |

|

|---|---|---|

| Population | -0.00 (-0.99) |

1.00 (-0.99) |

| GDP Per Capita | -0.00*** (-3.31) |

1.00*** (-3.31) |

| Agree in UN | 7.19*** -3.12 |

1327.22*** -3.12 |

| Participation WTO | 4.57*** (-2.71) |

96.59*** (-2.71) |

| 1. Participation IMG & WP | 4.68*** (-3.29) |

108.27*** (-3.29) |

| Years Ommited from Output | ||

| N | 2710 | 2710 |

t statistics in parentheses

* p<.10, ** p<.05, *** p<.01

In sum, the results indicate that during the last 17 years Brazilian Foreign Aid has targeted countries that hold similar political attitudes to Brazil in International Organizations. In contrast, economic characteristics appear to not have influenced the Brazilian decision to give foreign aid. Consequently, our findings confirm the hypothesis that Brazil is actively seeking political support to raise its profile in International Organizations.

International Cooperation during Economic and Political Turmoil

By the beginning of the current decade, Brazil had entered into a spiral of economic and political instability. Between 2010 and 2015 the country’s GDP dropped considerably, a clear negative trend with only 2013 as an exception. Moreover, the former president Dilma Rousseff was impeached, leaving room for institutional discredit and lack of vertical accountability (Luna & Vergara, 2016).

We can analyze the current crisis in Brazil from two perspectives. Firstly, as a consequence of the turmoil in the world economy that started with the American subprime mortgage collapse in 2008. It is worth mentioning that at first Brazil was not affected directly, as the country’s economy was powered by domestic demand, fueled by easy credit and growth rates of 7.5%. Nonetheless, after the first glimpse of domestic crisis, the Brazilian economy was hit hard, and presently the recovery still looks to be far away.

According to several sources, even if the Brazilian economy grows at 2% for the next four years, unemployment rates will only climb down to 2014 levels in 2021. This four-year growth would create 2.9 million jobs, the same amount that was lost between 2015 and 2016. In its annual report, the International Labor Organization (ILO) said that, across the world, one in every three people that lost their job in 2016 was Brazilian.

The other side of an economic crisis is its political consequences. In 2010, mainly due to Lula’s charisma and the inheritance of his popularity, Dilma Rousseff won the presidential election with 56% of the valid votes. Four years later, even though she managed to win re-election, her political credibility was at the limit. Economic problems, combined with her lack of support in Congress and the spillovers of judicial investigations, quickly eroded her good image. Ultimately, this scenario favored the appearance of an alternative political coalition, which destroyed the Workers’ Party majority in both Legislative houses. This political crisis, combined with the recession in the economy, set the stage for the impeachment process, which culminated with the departure of Rousseff from the presidency in 2016.

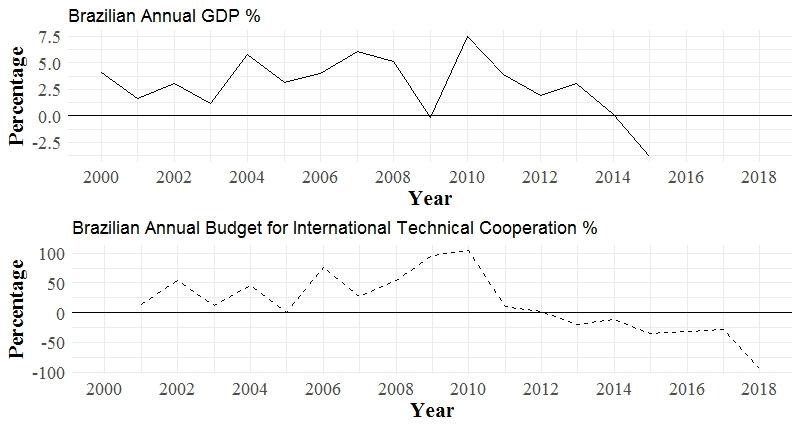

Given this context, what are the consequences of Brazil’s economic and political crisis for its international cooperation strategy? In economic terms, as can be seen in Figure 4, recession has a direct impact on the amount of money destined for international cooperation, either bilateral or multilateral. The units of both line charts are percentages, although they have different scales. Nonetheless, it is possible to observe that after 2010, when the Brazilian economy started to contract seriously, the funds made available for international cooperation has followed a similar path to the drop in GDP, with a more negative slope. In sum, the amount of money destined for cooperation has only diminished, with the exception of 2014, which can be explained as a result of the temporary recovery in 2013.

Figure 4: Brazilian Annual GDP % vs Brazilian Annual Budget

Graphs elaborated by the authors. Sources: World Bank and ABC data.

With respect to political effects, changes can be traced to before the 2016 impeachment. Rousseff was different in many aspects from her predecessor Lula, but the biggest difference was her attitude toward foreign policy. Since the beginning of her first term, it became clear that president Rousseff was more concerned with domestic issues than trying to have an active role in the country’s foreign policy formulation. This lack of importance inevitably had an impact on the country’s international profile (Cervo & Lessa, 2014; Saraiva, 2014). By way of an example, if at the end of Lula’s administration the budget of the ABC reached US$100 million, under Dilma’s government the amount plummeted to US$6 million, following a steady decrease that continued in 2016.

In this regard, with the change of administration, one of the most significant alterations was the appointment of José Serra as Minister of Foreign Affairs. In his first week in office, Serra ordered the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to conduct an evaluation of the cost and benefits of each Brazilian embassy. His argument was that the costs of maintaining several embassies, mainly those opened in Africa under Lula’s administration, were far greater than the economic gains from trade between Brazil and those African countries. After several discussions and the negative feelings generated by this initiative, José Serra backed off and decided to keep all the embassies open. Nevertheless, what has remained since then is the tendency to design policies within this cost-benefits framework, which contrasts with the Workers’ Party guidelines, according to which investing in soft power initiatives was considered to be a worthy policy even if it was unprofitable in the short term.

Having arrived at this point, we can say that, due to the lack of resources, the minor importance given to the country’s foreign policy and a change in the way of thinking about Brazil’s international integration, the once high-profile international cooperation strategy has weakened to a level whereby it only survives in intensive care. Thus, in the last section of our article we discuss the consequences of this switch, as well as the lessons we can apply to other rising powers.

Conclusions

During this century, changes in the distribution of power created a window of opportunity for rising powers to assume a more prominent position in the international arena. Regarding international cooperation, countries such as India, Turkey and Brazil have displayed more active roles, increasing the amount of funding for bilateral and multilateral international cooperation projects. In this sense, Brazil sought to increase its international profile by seeking international support in the current global order main International Organizations. We suggest that one of the tools used by Brazil to this end was the provision of technical cooperation. Our results suggest that the bulk of the technical cooperation provided in this period was directed to its main allies these IOs. Nevertheless, recent international and domestic changes have raised some concerns about the ability of rising powers to maintain a consistent policy on this issue.

From the international side, nowadays there is an increasing distrust in multilateral agencies, which can affect the international cooperation system as a whole. For instance, the United States has elected a president with negative views on international organizations, the United Kingdom has decided to leave the European Union, and right-wing parties with nationalistic views are gaining strength all around Europe. If this tendency keeps growing, and as a consequence multilateral initiatives are underfunded, the ability for rising powers to sustain an active role in international cooperation projects will be necessarily affected. The latter have benefited from a network of international organizations that, if weakened, will leave room for only bilateral initiatives, which require higher investments and do not benefit from the knowledge and expertise of developed countries.

From a domestic perspective, the main challenge rising powers face is their relative lack of material and human resources. On the one hand, emerging powers suffer from a duality: in absolute terms, they are big economies, but at the same time they still suffer from structural deficiencies. On the other hand, given the European crisis and the Chinese economic slowdown, most developing countries are now going through economic trouble, which will necessarily impact upon their ability to pursue an active international cooperation policy. In the end, both structural and short-term economic hurdles will make it harder for the governments of rising powers to convince their populations that investing in international cooperation should be a priority, principally when domestic needs are more pressing.

Moreover, and as we have seen for the Brazilian case, economic crises can give impetus to political ones. These domestic changes might not only affect a country’s reputation, but can lead to changes in their foreign policy. Consequently, the latter can raise doubts about the ability of a State to maintain its international commitments, which might also affect international cooperation projects that need time to mature.

Finally, away from this less optimistic opinion, we might highlight that rising powers still have something to say with respect to international cooperation. Their rise or fall will depend on their ability to sustain growth, to translate political will into domestic legitimacy and on their capacity to maintain policies through changes in government.

From the international side, nowadays there is an increasing distrust in multilateral agencies, which can affect the international cooperation system as a whole. For instance, the United States has elected a president with negative views on international organizations, the United Kingdom has decided to leave the European Union, and right-wing parties with nationalistic views are gaining strength all around Europe. If this tendency keeps growing, and as a consequence multilateral initiatives are underfunded, the ability for rising powers to sustain an active role in international cooperation projects will be necessarily affected. The latter have benefited from a network of international organizations that, if weakened, will leave room for only bilateral initiatives, which require higher investments and do not benefit from the knowledge and expertise of developed countries.

From a domestic perspective, the main challenge rising powers face is their relative lack of material and human resources. On the one hand, emerging powers suffer from a duality: in absolute terms, they are big economies, but at the same time they still suffer from structural deficiencies. On the other hand, given the European crisis and the Chinese economic slowdown, most developing countries are now going through economic trouble, which will necessarily impact upon their ability to pursue an active international cooperation policy. In the end, both structural and short-term economic hurdles will make it harder for the governments of rising powers to convince their populations that investing in international cooperation should be a priority, principally when domestic needs are more pressing.

Moreover, and as we have seen for the Brazilian case, economic crises can give impetus to political ones. These domestic changes might not only affect a country’s reputation, but can lead to changes in their foreign policy. Consequently, the latter can raise doubts about the ability of a State to maintain its international commitments, which might also affect international cooperation projects that need time to mature.

Finally, away from this less optimistic opinion, we might highlight that rising powers still have something to say with respect to international cooperation. Their rise or fall will depend on their ability to sustain growth, to translate political will into domestic legitimacy and on their capacity to maintain policies through changes in government.

Notes

Funding

This research was supported by Grant 2013/23251-9 and Grant 2015/12860-0, Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP).

References

Abdenur, AE & Fonseca, JMEMD 2013, ‘The North’s Growing Role in South–South Cooperation: keeping the foothold’, Third World Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 8, pp. 1475–1491.

‘Africanos temem perda de espaço no novo governo brasileiro – Mundo – iG’ Último Segundo, retrieved February 25, 2017, from <http://ultimosegundo.ig.com.br/mundo/2016-06-05/africanos-temem-perda-de-espaco-no-novo-governo-brasileiro.html>.

‘Agência Brasileira de Cooperação’, retrieved February 25, 2017, from <http://www.abc.gov.br/>.

‘Agência Brasileira de Cooperação’, retrieved February 25, 2017, from <http://www.abc.gov.br/Content/ABC/docs/ManualDiretrizesCooperacaoRecebida.pdf>.

Alesina, A & Dollar, D 2000, ‘Who Gives Foreign Aid to Whom and Why?’, Journal of Economic Growth, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 33–63.

Apolinário Junior, L 2016, ‘Foreign aid and the governance of international financial organizations: the Brazilian-bloc case in the IMF and the World Bank’, Brazilian Political Science Review, vol. 10, no. 3, retrieved February 25, 2017, from <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1981-38212016000300206&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en>.

Carmody, P 2017, The New Scramble for Africa, John Wiley & Sons.

Cervo, AL 1994, ‘Socializando o desenvolvimento: uma história da cooperação técnica internacional do Brasil’, Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 37–63.

Cervo, AL & Lessa, AC 2014, ‘The fall: the international insertion of Brazil (2011-2014)/O declinio: insercao internacional do Brasil (2011-2014)’, Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, vol. 57, no. 2.

Chaturvedi, S 2012, ‘Characteristics and Potential of Triangular Development Cooperation (TDC): Emerging Trends, Impact and Future Prospects’, New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available online at <http://www.un.org/en/ecosoc/newfunct/pdf/tdc_study.pdf>(accessed on December 20, 2015).

Costa Leite, I, Suyama, B, Trajber Waisbich, L, Pomeroy, M, Constantine, J, Navas-Alemán, L, Shankland, A & Younis, M 2014, Brazil’s engagement in international development cooperation: the state of the debate, ids.

Dauvergne, P & Farias, DB 2012, ‘The Rise of Brazil as a Global Development Power’, Third World Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 903–917.

‘Discurso do ministro José Serra por ocasião da cerimônia de transmissão do cargo de ministro de estado das Relações Exteriores – Brasília, 18 de maio de 2016’, retrieved February 25, 2017, from <http://www.itamaraty.gov.br/pt-BR/discursos-artigos-e-entrevistas/ministro-das-relacoes-exteriores-discursos/14038-discurso-do-ministro-jose-serra-por-ocasiao-da-cerimonia-de-transmissao-do-cargo-de-ministro-de-estado-das-relacoes-exteriores-brasilia-18-de-maio-de-2016>.

Dreher, A, Nunnenkamp, P & Thiele, R 2008, ‘Does US aid buy UN general assembly votes? A disaggregated analysis’, Public Choice, vol. 136, no. 1–2, pp. 139–164.

Faria, CAP de & Paradis, CG 2013, ‘Humanism and solidarity in brazilian foreign policy under Lula (2003-2010): theory and practice’, Brazilian Political Science Review, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 8–36.

Filho, WV 2007, O Brasil e a crise haitiana: a cooperação técnica como instrumento de solidariedade e de ação diplomática, Thesaurus Editora.

Fordelone, TY 2009, ‘Triangular Co-operation and Aid Effectiveness1’, Paper presented at the OECD/DAC Policy Dialogue on Development Co-operation (Mexico City, vol. 28, p. 29.

Fukuyama, F 2006, The End of History and the Last Man, Simon and Schuster.

G1, DA & Paulo, em S 2016, ‘Brasil só deve recuperar estoque de empregos perdidos a partir de 2021’, Concursos e Emprego, retrieved February 25, 2017, from <http://g1.globo.com/economia/concursos-e-emprego/noticia/2016/08/brasil-so-deve-recuperar-estoque-de-empregos-perdidos-partir-de-2021.html>.

Hirst, M 2012, Aspectos conceituais e práticos da atuação do Brasil em cooperação Sul-Sul: Os casos de Haiti, Bolívia e Guiné Bissau, Texto para Discussão, Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (IPEA), retrieved February 25, 2017, from <https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/91086>.

‘IMF — International Monetary Fund Home Page’, retrieved June 24, 2017, from <http://www.imf.org/external/index.htm>.

IPEA, A 2010, ‘Cooperação Brasileira para o Desenvolvimento Internacional: 2005-2009’, Brasilia: Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (IPEA), Agência Brasileira de Cooperação (ABC).

IPEA, A 2013, ‘Cooperação Brasileira para o Desenvolvimento Internacional: 2010’, Brasilia: Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (IPEA), Agência Brasileira de Cooperação (ABC).

IPEA, A 2016, ‘Cooperação Brasileira para o Desenvolvimento Internacional: 2011-2013’, Brasilia: Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (IPEA), Agência Brasileira de Cooperação (ABC).

Kuziemko, I & Werker, E 2006, ‘How Much Is a Seat on the Security Council Worth? Foreign Aid and Bribery at the United Nations’, Journal of Political Economy, vol. 114, no. 5, pp. 905–930.

Lancaster, C 2008, Foreign Aid: Diplomacy, Development, Domestic Politics, University of Chicago Press.

Langendorf, J 2012, ‘Chapter 3 – Initiation of Triangular Cooperation’, in Triangular Cooperation, Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG, pp. 59–76.

Leite, IC 2012, ‘Cooperação Sul-Sul: conceito, história e marcos interpretativos’, Observatório Político Sul-Americano, vol. 7, no. 3.

Luna, JP & Vergara, A 2016, ‘Latin America’s Problems of Success’, Journal of Democracy, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 158–165.

McKinley, RD & Little, R 1979, ‘The US Aid Relationship: A Test of the Recipient Need and the Donor Interest Models’, Political Studies, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 236–250.

McEwan, C & Mawdsley, E 2012, ‘Trilateral Development Cooperation: Power and Politics in Emerging Aid Relationships’, Development and Change, vol. 43, no. 6, pp. 1185–1209.

Milani, CRS & Carvalho, TCO 2013, ‘Cooperação Sul-Sul e Política Externa: Brasil e China no continente africano’, Estudos internacionais: revista de relações internacionais da PUC Minas, vol. 1, no. 1, retrieved February 25, 2017, from <http://200.229.32.55/index.php/estudosinternacionais/article/view/5158>.

Ministério das Relações Exteriores, 2008, ”Discursos Selecionados do Presidente Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva”. Fundação Alexandre Gusmão, retrieved February 25, 2017, from <http://www.funag.gov.br/loja/download/505-discursos_selecionados_lula.pdf>.

OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms – Official development assistance (ODA) Definition’, retrieved February 25, 2017, from <http://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=6043>.

OECD 2013, Triangular Co-operation: What’s the Literature Telling Us? Literature review prepared by the OECD Development Co-operation Directorate, retrieved February 25, 2017, from <https://www.oecd.org/dac/dac-global-relations/OECD%20Triangluar%20Co-operation%20Literature%20Review%20June%202013.pdf>.

Oliveira, AJ & Onuki, J 2012, ‘South-South cooperation and Brazilian foreign policy’, Foreign Policy Research Center Journal. Vol. 3, pp. 80-99.

Pinheiro, L, Gaio, G, Pinheiro, L & Gaio, G 2014, ‘Cooperation for Development, Brazilian Regional Leadership and Global Protagonism’, Brazilian Political Science Review, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 8–30.

Pinheiro, L, Lima, M & Hirst, M 2010, ‘A política externa brasileira em tempos de novos horizontes e desafios’, Nueva Sociedad Especial em Português, December.

Pino, BA 2012, ‘Contribuciones de Brasil al desarrollo internacional: coaliciones emergentes y cooperación Sur-Sur / Brazil’s contributions to international development: emerging coalitions and South-South cooperation’, Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals, no. 97/98, pp. 189–204.

Pino, BA & Leite, IC 2009, ‘O Brasil e a Cooperação Sul-Sul: Contribuições e Desafios’, Meridiano 47, vol. 10, no. 113, p. 19.

Prashad, V 2013. ‘Neoliberalism with Southern characteristics. The rise of the BRICS’. Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, New York Office. retrieved June 22, 2017, from: <http://www. rosalux-nyc. org/wp-content/files_mf/prashad_brics. pdf>.

Puente, CAI 2010, A cooperação técnica horizontal brasileira como instrumento da política externa: a evolução da cooperação técnica com países em desenvolvimento-CTPD-no período 1995-2005, Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão.

Quadir, F 2013, ‘Rising Donors and the New Narrative of “South–South” Cooperation: what prospects for changing the landscape of development assistance programmes?’, Third World Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 321–338.

Renzio, P de & Seifert, J 2014, ‘South–South cooperation and the future of development assistance: mapping actors and options’, Third World Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 10, pp. 1860–1875.

Rhee, H 2011, ‘Promoting South-South cooperation through knowledge exchange’, Catalyzing Development. A New Vision for Aid (Washington, DC, Brookings Institute), pp. 260–280.

Rossi, A 2011, ‘Brasil, um país doador’, Le Monde Diplomatique Brasil, vol. 1.

Saraiva, MG 2014, ‘Balanço da política externa de Dilma Rousseff: perspectivas futuras?’, Relações Internacionais (R:I), no. 44, pp. 25–35.

‘Serra pede estudo de custo de embaixadas na África e no Caribe – 17/05/2016 – Mundo – Folha de S.Paulo’, retrieved February 25, 2017, from <http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mundo/2016/05/1771982-serra-pede-estudo-de-custo-de-embaixadas-na-africa-e-no-caribe.shtml>.

Six, C 2009, ‘The Rise of Postcolonial States as Donors: a challenge to the development paradigm?’, Third World Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 1103–1121.

Souza, A M 2012, ‘A cooperação para o desenvolvimento sul-sul: os casos do Brasil, da Índia e da China’ Boletim de Economia e Política Internacional (BEPI), Brasília, n. 9.

Strezhnev, A & Voeten, E 2012, ‘United Nations General Assembly voting data: August 2012’,.

Vreeland, JR 2011, ‘Foreign aid and global governance: Buying Bretton Woods – the Swiss-bloc case’, The Review of International Organizations, vol. 6, no. 3–4, pp. 369–391.

‘World Bank Group – International Development, Poverty, & Sustainability’ World Bank, retrieved June 24, 2017, from <http://www.worldbank.org/>.

‘World Trade Organization – Home page’, retrieved June 24, 2017, from <https://www.wto.org/>.