The Russian Approach to Public Diplomacy and Humanitarian Cooperation

Download this article in PDF formatAbstract

In Russia, Public Diplomacy [PD] is viewed as engaging foreign target audiences by fostering cooperation in political, economic, and cultural spheres. This is done with the purpose of promoting the national interests of the home country.1 A hallmark feature of Russian public diplomacy is not using “countering” component against foreign propaganda/violent extremism, that is seen as the part of the strategic communications, not PD narrative. Unlike public diplomacy of Western countries Russian PD is not focused on exporting democracy but is aimed at promoting international dialogue and strategic stability among various international players. Russian PD is used mainly for attracting allies and buiding dialogue with the difficult partners. Through its public diplomacy and humanitarian cooperation Russia promotes the message that the nation state is the only reliable guarantor of international peace and stable world order.

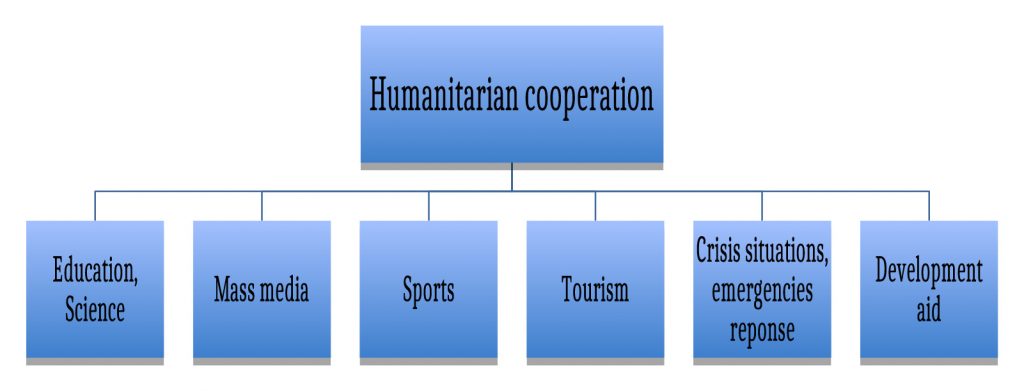

This paper will also give an insight into humanitarian cooperation, which is widely used by the Post-Soviet states and although being to some exent synonymous to PD, it has some unique features while being even broader than PD. Besides including such traditional PD components as cooperation in the sphere of education, science, arts, sports, tourism and mass media, humanitarian cooperation also includes humanitarian assistance in crisis situations and development aid. Yet it has nothing in common with the humanitarian interventionism.

Keywords

Introduction

In the paper, the author searches for a framework to analyse Russian PD and humanitarian cooperation: what are its goals, actors and instruments. Although Russian public diplomacy is attracting a growing research interest, it is still a much understudied field, even in Russia. Western perspectives usually analyze Russian PD though the lens of strategic communication and hybrid warfare, while in Russia PD is seen as an instrument of dialogue, not containment.

Since the end of the Cold War until early 2000s Russian programmes on involving foreign audience were substantially cut. It was a unilateral disarmament in this sphere. The necessity for using PD and humanitarian cooperation more actively was realized in Russia during the early 2000s (after the failure of messaging its position on NATO airstrikes of Serbia to the international community and after acquiring substantial financial opportunities due to the oil boom that had happened then). That is the reason why all mechanisms of its participation in the engagement with foreign audiences and international development assistance have only been recently re-established. This research will give an analysis of these initiatives and institutions, as well as include an overview of the main regional priorities of Russian PD and its humanitarian cooperation.

Public Diplomacy in the Russian Context

In different countries public diplomacy has various forms, methods, and aspects. In Russia, as well as throughout the majority of Post-Soviet countries, it is viewed as engaging foreign audiences through fostering of cooperation in political, economic, and cultural spheres with the purpose of promoting country’s national interests Whereas in Western countries (especially the U.S.) PD combines two components – engaging allies (mainly through educational and cultural activities) and confronting enemies (such as violent extremism and foreign propaganda through the use of strategic communications) [Tsvetkova 2016]2 in Russia, PD is perceived as aiming to create an objective and favorable image of country [Borishpoletz 2016]3, without undermining the efforts of other actors [Zonova 2012]4. The point of this is that it is seen in Russia that public diplomacy can hardly be combined with strategic communications, seen as having influential channels to work with foreign audiences, the necessity of which was realized in Russia after 1999. This occurred as a result of “CNN effect,” in which Russia could not effectively present its position on the NATO airstrikes on Serbia to the international public. As a result of a number of failures in shaping global public opinion in respect to its policy agendas Russia developed its own international broadcasting tools such as Russia Today, Sputnik news agency, TASS news agency and Russia Direct. However, an analysis of Russia’s international broadcasting tools which are frequently criticized by Western outlets as propaganda is beyond the scope of this paper due to the fact that in Russia, it is seen as more a part of the strategic communications narrative, rather than PD.

It is necessary to note that the term “public diplomacy” is not widely used in official Russian discourse. The most recent foreign policy concept states – “developing, including through public diplomacy, international, cultural, and humanitarian cooperation as a means to build up dialogue among civilisations, to achieve consensus, and to ensure understanding among peoples with a particular emphasis on inter-religious dialogue” and “greater participation of Russia’s academics and experts in the dialogue with foreign specialists on global politics and international security as one of the areas of public diplomacy development”5. The Russian original of this text uses the terms “obshchestvennaya,” “people to people (P2P),” and “citizen” rather than that of public diplomacy. Due to this, priority is given to the practice adopted by the Soviets, known as “people-to-people” (P2P) and “citizen diplomacy,” which is more familiar to the current generation of decision-makers. Nevertheless, the specific foundation established by Ministry of Foreign Affairs [MFA] is called the “Public diplomacy Foundation.”

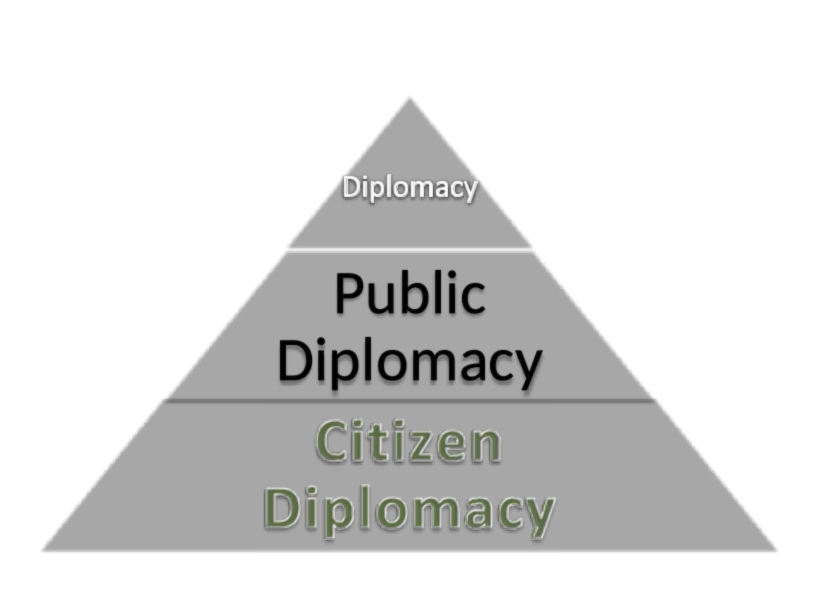

However, Russian experts and specialists working in the field distinguish all of these terms separately. We can then suggest the following scheme.

Graphic 1: Diplomacy/Public Diplomacy/Citizen Diplomacy Scheme

According to this scheme, Citizen or P2P diplomacy deals with grassroots initiatives: twin cities, cultural exchanges between neighboring countries (e.g. festival of the young composers of Russia and Kazakhstan), etc.

Public diplomacy, on the other hand, is closer to the goals of official diplomacy often intersecting with Track II diplomacy (e.g. Russian – US expert meetings, such as the most recent Russian-U.S. Conference on Arms Control hosted by the US-Canada Studies Institute, RAS, and the Gorchakov Foundation).

So, the practice and terminology of PD is different in Russia and it is not the same as its Western alternatives, as it includes the elements of engagement, but it does not include the elements of countering (foreign propaganda/terrorist threats6), which are supposed to be the part of the strategic communications narrative. Besides, the term is interpreted in a much narrow sense in Russia in comparison to other countries [Velikaya 2018]7, as far as in Russia there are separate spheres for public and citizen diplomacy. Moreover, a lot of PD initiatiatives are part of the humanitarian cooperation (that will be analysed below). So, if in Western terminology public diplomacy includes citizen diplomacy and humanitarian cooperation (as well as the strategic communication component on confronting enemies), in Russian tradition these terms are separated, although the recent trends demonstrate that maybe in the nearest time there will be some merger of the terms (mainly due to the digital diplomacy, which unites public diplomacy and strategic communications and due to the hawkish aspirations of some politicians, willing to show “Kuzka’s mother” to foreign rivals through various means, including through PD).

Humanitarian Cooperation

Both Russia and Post-Soviet countries have a unique approach towards humanitarian cooperation: it is seen as being more broader than international development cooperation and international aid or even broader than public diplomacy. Meanwhile it is necessary to empathise that humanitarian cooperation has nothing in common with the Western doctrines of humanitarian interventionism and the responsibility-to-protect (R2P) used as the pretext for the regyme changes, seen by Russia and its allies as one of the practices undermining stable world order. Humanitarian cooperation covers cooperation in the sphere of education, science, arts, sports, tourism, and mass media. These are the areas that are traditionally seen as part of PD in other countries [Simons 2018]8.

So, although humanitarian cooperation is a foreign policy instrument, because of the diversity of its actions it attracts a great variety of activities and actors involved.

As far as it is hardly possible to cover all the Russian humanitarian cooperation activities in frames of one article here we would like to highlight its international humanitarian aid dimension. From 1954 through 1989, the Soviet Union had spent on it $144.3 billion. This consisted of the constructions of 3575 objects (schools, hospitals, infrastructural objects). To illustrate, the Soviet Union funded the Tehri dam in India, the Aswan dam in Egypt, the Salung tunnel in Afghanistan, and the Gelora Bung Karno Stadium in Indonesia. It was the price they paid in order to have the other countries to choose a socialist orientation. After the collapse of the Soviet Union at the beginning of 1990s and up through 2005, Russia itself was a recipient of humanitarian aid, and only since 2006 has it again become an international donor9. This is why all of the mechanisms of its participation in the process of international development aid are currently under construction.

Until 2014, Russian aid was given through the international UN-affiliated structures, World Economic Forum and World Bank. However, after 2014, Moscow had realized that the huge sums of money being spent by Russia on International aid had to be labeled “from Russia with love”. Ukrainian events have revealed then that regardless of all Russian efforts, the great part of the civil society of the neighboring country is strictly opposed not only to Russian policy but towards Russia’s vision of the world order. The reasons for this trend should be scrupulously analysed. When considering representative Ukrainian example, it should first be mentioned that Russia’s approach was based on special relationships with Ukrainian elites while neglecting work with civil society and the academic community. In the last two decades, Russia has invested more than two hundred billion dollars in the Ukrainian economy10, while the United States has invested five billion dollars “in the development of democratic institutions and skills in promoting civil society and a good form of government”11. Therefore, Russian donation policy towards Ukraine has proved to be inefficient. Besides, Russian NGOs were working only with the so-called “young leaders,” neglecting the work with the professional or academic society. Maybe Western experience was also taken in mind: economic aid to different countries that could be seen as a positive story does not guarantee loyalty – for example, Pakistan receives annually $500 billion of humanitarian aid, while 74% of the population perceive the US as the rival (in 2012, compare to 64 % in 2009)12. This realization is what led to the adoption of the concept of the Russian State Policy in the Area of International Development Assistance. It has moved its priorities from international institutions towards a more regional direction (like it was in Soviet times while constructing infrastructural objects abroad). Russia has started pursusing an active and targeted policy in the field of international development assistance which served “the national interests of the country, contributed to the stabilization of the socio-economic and political situation in partner states and the formation of good-neighbourly relations with neighbouring states, facilitated the elimination of existing, and the potential hotbeds of tension and conflict, especially in the neighbouring regions, as well as helped strengthen the country’s positions in the world community and, eventually, create favourable external conditions for the development of the Russian Federation”13. In this regard a landmark Partnership Framework Agreement was signed between the Russian Federation and United Nations Development Programme [UNDP]14 creating a foundation for a long-term strategic partnership with Russia which has marked a transition to its role as a donor to UNDP. Russian humanitarian cooperation has become more region-oriented and target-focused.

After analysing theoretic framework of Russian PD and humanitarian cooperation it would be necessary to highlight several key points of its realization, namely – message, actors involved and regional priorities.

Message

Russia promotes a message of support for multilateralism, the central role of the United Nations in international affairs with the role of safeguarding nation state’s sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity15, and the non-interference in internal affairs. With this message, Russia looks for partners to help promote this message – be it EAEU (Eurasian Economic Union), SCO (Shanghai Cooperation Organisation), BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa), or other integration formats.

Russia’s public diplomacy and humanitarian cooperation are and will countiue to work to counter what G.F Kennan called “the legalistic-moralistic approach” to international problems. Russia insists that coercive democratization can bring nothing but harm to states with a specific way of development and that the nation-state is the only reliable guarantor of world order. This is the difference of Russian PD, unlike American and other Western efforts it is not focused on exporting democracy (liberal democracy). PD events usually attract representatives of official institutions ana academia, not those who can be seen as opposition. Russia has learnt its lessons from the mistakes and miscalculations of Western PD. When its message sent abroad – that values prevail over national interests – on the one hand created loyal followers in different countries, but on the other – caused the growth of anti-Americanism and anti-Westernism worldwide. E.g. the current migration crisis (that according to EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini16 and the ex-U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry17 encompasses a total of 12 million people) is seen by some Europeans as caused by the U.S. nation-builiding experiments in the Middle East and Northern Africa, coercive democratization. So, humanitarian interventionism effects badly Western public diplomacy initiatives. As it was said by ex-President Obama, “When we deploy troops, there’s always a sense on the part of other countries that, even where necessary, sovereignty is being violated”18.

And therefore Russia’s position on Syria, Iraq, and Libya translated through PD and strategic communications mechanisms was warmly welcomed by millions of ordinary people all over the world. However, Russia still has much-untapped potential in offering its own framework on international engagement through PD methods. Besides protecting the “free world” by countering coersive democratization another Russian message is protecting traditional values. According to Professor Nicholas J. Cull19, when analyzing these Russian PD efforts we should admit that they find understanding in many corners of the world. Russian image as protector of traditional values is promoted by Russian authorities: according to President Putin, today, when traditional values are already being eroded in many countries more and more people are looking at Russia as a bearer of immutable traditional values and a healthy human lifestyle20. Russian PD machine raises these questions on various international platforms: from the young leaders forums to the side events of the UN-affiliated meetings.

Actors

In Russia, PD and humanitarian cooperation are closely correlated with national interests, national security, and foreign policy goals – making them instruments of Russian foreign policy that are usually implemented by government-affiliated institutions.

In the last decade, Russia has made serious efforts in the sphere of advancing its public diplomacy practice. Significant status was given to the Rossotrudnichestvo Federal agency.21 Structures such as the Alexander Gorchakov Public Diplomacy Foundation22, the Russian Council23, the Russkiy mir Foundation24, and the Fund to Support and Protect the Rights of Compatriots Living Abroad were created. New media projects like Russia direct25 and Russia beyond the headlines26 were launched

Still, the key actors within the sphere of PD and humanitarian cooperation are the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Rossotrudnichestvo Federal Agency (part of the MFA body), the Gorchakov Foundation, the Russian International Affairs Council and, the Ministry for Emergency Situations. Also, Russian NGOs (e.g. the Russian Humanitarian Mission, Creative Diplomacy and The Institute for Literary Translation) and think tanks (the Valdai Club27, PIR-Center28, the Russian Committee for BRICS research29, and the Council on Foreign and Defence Policy30, Network of Eurasian studies31, Berlek-Center32) are active participants of Russian PD. Russian academic, cultural and sports diplomacy are also part of this process. But generally we can assume that Russian public diplomacy is state-centric and consists of the following state-based PD initiatives.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs coordinates a substantial part of Russian PD and humanitarian cooperation. Russia spends around $120 million annually via its mechanisms in order to sustain more than 45 humanitarian operations around the globe. “The annual volume of Russian aid within the WFP exceeds $30 million. Apart from that, humanitarian assistance is sent through the International Civil Defence Organisation (ICDO)”33. Through the MFA, Russian humanitarian aid is distributed mainly to international organizations specializing in this sphere. Besides, the MFA coordinates the work of other structures that will be analysed below. Russsian MFA also promotes new PD formats, for example, a network of Eurasian, BRICS, European, and the Young Diplomats Forum. The First Global Forum of Young Diplomats was held in Sochi in 2017 as part of the World Festival of Youth and Students. The event was the culmination of over four years of work by the Russian Foreign Ministry’s Council of Young Diplomats, who held similar regional forums in which only young diplomats took part34. In total, the final document of the Global Forum on the establishment of the International Association of Young Diplomats was supported by more than sixty states. Besides, somen women diplomats are said to be working on the concept of the International women diplomacts league. Such projects are rather effective in promoting country’s PD among foreign audience.

Federal Agency for the Commonwealth of Independent States Affairs, Compatriots Living Abroad, and International Humanitarian Cooperation (Rossotrudnichestvo) operates under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation.

It is aimed towards the implementation of the state policy of international humanitarian cooperation and the promotion of an “objective” (that’s the word preferred by Sergey Lavrov to “positive”35) image of contemporary Russia. It is represented in eighty different states across the world by ninety-five representative offices: seventy-two Russian centers of science and culture in sixty-two states, twenty-three representatives of the Agency serving in Russian Embassies in twenty-one states. Rossotrudnichestvo Representative Offices abroad provide “technical assistance to recipient states, including the exchange of knowledge, skills, scientific and technical expertise in order to develop institutional and human capacities of the partner states”36.

The agency promotes Russian education services and extends cooperation between educational institutions of partner states. Rossotrudnichestvo launched the RUSSIA.STUDY project, which operates in eleven different languages, with the aim of attracting potential students to its universities. Russia provides annually fifteen thousand places for foreigners to study for free (this number is not so great, as far as only Romania annually gives Moldavia 5000 fully covered scholarships). The agency also pays great attention to working with alumni of Russian (Soviet) higher education institutions, the number of which exceeds five-hundred thousand37.

One of the principal guidelines of action of Rossotrudnichestvo is international development assistance (IDA). To implement this task, it coordinates Russian work with the Russian – UNDP Trust Fund for Development. It promotes Russian assistance towards neighboring states shifting from the non-specified aid under the aegis of different international organizations towards targeted aid.

Unfortunately, Rossotrudnichestvo has offices abroad but some representatives demonstrate disrespect for local culture and languages. This seen with their lack of knowledge of local culture and language after years of staying within the country (especially in Post-Soviet space) or instead of organizing conferences they are annually hosting craft doll exhibitions, calling it the most bright event of the year38.

The Gorchakov Public Diplomacy Foundation (with Executive director Leonid Drachevsky, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, 1998 – 1999, Minister for CIS affairs, 1999 – 2000) was established by the MFA in 2010 to promote Russian public diplomacy initiatives. Its activities have had two dimensions: giving grants to Russian and foreign NGOs and hosting academic events in Russia and abroad. The head of the board of trustees is the Minister of Foreign Affairs. As it was mentioned by Sergey Lavrov recently, the priority of the foundation’s activities is currently the consolidation of ties in the post-Soviet space, the development of ties between Russia and Euro-Atlantic countries, and the promotion of international cooperation in countering new challenges and threats39. It is worth mentioning the Track II diplomacy initiatives conducted by the Foundation – e.g. the international conference “Russian-American Relations: 210 Years” organized jointly with the Russian Academy of Sciences Institute of US and Canadian Studies and the Kennan Institute.

The Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC) (with President Igor Ivanov, the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1998 to 2004) is a diplomatic think tank that is aimed at “strengthening peace, friendship, and solidarity between peoples, preventing international conflicts, promoting conflict resolution and crisis settlement, and operating as a link between the state, scholarly community, business, and civil society in an effort to find foreign policy solutions to complex conflict issues”. Its mission is to facilitate Russia’s peaceful integration into the global community, partly by organizing greater cooperation between Russian scientific institutions and foreign analytical centers/scholars on the major issues of international agenda40.

The Ministry of the Russian Federation for Civil Defence, Emergencies, and the Elimination of Consequences of Natural Disasters (the Emergencies Ministry)

Russian humanitarian assistance within the frame of crisis response is conducted by the Emergencies Ministry, within which is established the Agency for Support and Coordination of Russian Participation in International Humanitarian Operations (EMERCOM)41. Its tasks are to support and coordinate participation in international humanitarian operations, which are carried out under the aegis of the UN and other international organizations. Since 2014, this Agency is a technical partner of the UN World Food Programme. It coordinates the National Russian Corps of emergency humanitarian response that has given help to sixty different countries and participated in the implementation of dozents of International humanitarian rescue operations abroad (in Afghanistan, Rwanda, Ethiopia, Uganda, Transdniestria, Bolivia, Myanmar, and many other countries)42. The Emergencies Ministry specialists also train foreign representatives in the educational centers of the Ministry (e.g. the professional development of Kirghiz specialists43).

We can outline that within the frame of the Russian Emergencies ministry, Russian humanitarian assistance is given towards conflict-affected societies or towards states facing emergency situations. An example can be seen in the recently established Russian-Serbian Humanitarian Center – a joint project of Russian and Serbian government – where rescuers from all Balkan countries are educated on the correct actions to be taken in emergency situations. The center is described as “Being an active participant in the social life of Serbia. It cooperates with the non-governmental, religious and veterans’ organizations, schools, and media. In the future, the Center is seen as a fully functional international structure that provides help in the field of emergency humanitarian response to Balkan countries that are interested in it”44. This Center is a vivid example of the Russian humanitarian assistance to the Balkan region, which is of huge historical importance to the country.

Non-governmental Organizations [NGOs]

Unfortunately, Russian civil society is not widely involved in public diplomacy. There are various reasons for this – from the administrative barriers to the misunderstanding of businesses on the importance of nation branding. We are also witnessing the lack of actors, especially of independent ones. Russian civil society involved in international cooperation is legally cut from Western finances, while local resources may be received mainly from administrative institutions45. In the result, as it is mentioned by Professor Tatiana Zonova, “currently, there are 51 Russian NGOs that enjoy consultative status with the ECOSOC – this amounts to only 1.5% of the total number of NGOs worldwide with such a status”46. Enthusiasts coming into this field can hardly survive in this atmosphere. Unfortunately, Russia does not give broad chances for self-realization for the people involved in its humanitarian and public diplomacy programmes. Russia does not have a lot of international companies or foreign-oriented NGOs where these alumni could be working However, there is growing support and understanding for the necessity of attracting active people into this field. The Minister of Foreign Affairs annually meets with the representatives of the foreign-oriented NGOs47.

Academic Diplomacy

Since around the Cold War, Russian academic society was actively involved in fostering public diplomacy dialogue, not only with the Warsaw Pact but also with NATO member countries. Moscow was hosting various academic conferences; Soviet scholars were goodwill ambassadors of their country. Here, we can remember the example of the physicist Kapitza who was staying in Cambridge – he was one of Lord Rutherford’s brightest students. Regardless of the difficult relationships between Britain and the USSR, the cutting-edge Mond laboratory was sold to the USSR in 1935. And Lord Rutherford’s favorite student and dearest friend became a Nobel-Prize winner.

Russian scholars and academic diplomacy held a serious role during the détente movement. Expert communities had a positive experience when it came to drafting the Non-Proliferation Treaty (1968), negotiating its’ permanent extension (1995), minimizing the outcomes of military nuclear programs in Democratic People’s Republic of North Korea, India, Iraq, Pakistan, South Africa. The Dartmouth conference, the Aspen security forum, the Russian-US working group on the non-proliferation (NPT) and strategic stability, the Elba group, IMEMO – Carnegie 2012-Euro-Atlantic Security Initiative, and the Fletcher-MGIMO Conference on U.S.-Russia Relations – are important parts of the Russian-US public diplomacy dialogue48.

Regardless administrative difficulties, Russian science is rapidly developing: Russia is one of seven leading countries in terms of its number of Nobel Prize winners. In addition, it is thirteenth of two-hundred and thirty-nine in the SCImago Journal & Country Rank global science rating49. Russia has and continues to play a leading role in space exploration and has some of the safest nuclear technology. These achievements contribute significantly to promoting Russia as one of the major scientific powers in the world, but these resources are quite underused in the PD sphere (some of its reasons will be covered below). A vivid positive example of academic diplomacy is the Primakov readings50 held annually by The Primakov Institute of World Economy and International Relations of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IMEMO) which are aimed at promoting cooperation between the leading international relations scholars and decision-makers. It is ranked by the Pennsylvania University Global think tank index51 as among top ten world discussion platforms. Such initiatives contribute greatly towards Russia’s public diplomacy.

As for the cultural dimension of Russian public diplomacy, Russian literature, ballet, and art are internationally recognized. Names such as Feodor Dostoevsky, Anton Chekhov, Petr Tchaikovsky, Sergey Rachmaninoff, Dmitry Shostakovich, Georgiy Sviridov, and Sergey Prokofiev are among the best advocates for Russia. When Valeriy Gergiev and Denis Matsuev performed at Carnegie Hall during the current deterioration of the Russian-American relationship, they were warmly welcomed by the New York crème de la crème. In this case, artists acted as goodwill ambassadors of their country. According to Simon Anholt, he first heard of Russia’s capital through the phrase “Oh, to go to Moscow, to Moscow!” from Anton Chekhov’s The Three Sisters52. Moscow for him was a place one had to strive to get to, regardless of anti-Soviet propaganda efforts. Russian culture is a powerful resource for PD and humanitarian cooperation, but it also has much-untapped potential53.

If we look at the sports dimension of Russian public diplomacy we can say that Russia is using it rather efficiently54: be it Universiade-2013, Olympic games-2014, or FIFA World Cup-2018. As President of the International Olympic Committee, Thomas Bach told in his interview, “We arrived with great respect for the rich and varied history of Russia. We leave as friends of the Russian people”55. Unfortunately, regardless of the active work in this sphere, the partial disqualification of the Russian Olympic team and the whole Paralympic team during Rio Olympic games – 2016 had to some extent undermined their positive achievements.

When analysing Russian public diplomacy actors, it is necessary to summarize that the main problem of Russian public diplomacy is a lack of strategic planning. Russian PD needs to undergo a thorough audit. It is necessary to attract well-informed, as well as critical scholars and practitioners, who are capable of making their assessments and suggestions heard by the decision-makers. Although currently Russian PD and humanitarian cooperation is coordinated mainly by government-affiliated institutions and NGOs, it could involve a wide array of external business and cultural agents.

Regional Priorities

Regional priorities of Russian PD and humanitarian cooperation may be divided into two groups: the first one is Russia’s top priority which entails a number of countries under former Soviet Union. The second one is other countries that need foreign aid, are considered difficult partners and those that are interested in dialogue. There is a notable ideological alliance with the former while the latter group represents nations that Russia is seeking to build better relations outside of the Soviet sphere of influence.

The Eurasian region is the region of top priority for Russian foreign policy goals56.

A great amount of Russian PD attempts is realized through the Commonwealth of independent states (CIS, member states – Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan).

The key multilateral mechanism for conducting the humanitarian cooperation of the CIS is the Intergovernmental Foundation for Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Cooperation (IFESCCO) created in 2006. Its mission is to contribute to the further development of humanitarian cooperation and intercultural communication in the Commonwealth of Independent States in the area of education, science, culture, mass communications, information, archives, sports, tourism, and youth matters.

IFESCCO operates in close cooperation with the Council for Humanitarian Cooperation of the Member States of the CIS (the “Council for Humanitarian Cooperation”). Since its establishment, it has supported over one-hundred international projects in the area of humanitarian cooperation, the main of which are: the annual forum of Creative and Scientific youth, Intellectuals of the CIS Member States, prizes awarded by the Council for Humanitarian Cooperation and IFESCCO, the Youth Symphony Orchestra of the CIS, higher education courses of the CIS for young scientists, international summer school for young historians from the CIS counties, trainings for CIS countries in museum management, theater fairs and film festivals57. The humanitarian agenda of the CIS states is quite rich and is one of the key spheres of cooperation in this integration body. Multilateral and bilateral projects are rather diverse, but making them known to the general public is very important. For example, fifty percent of the budget of the Union state of Russia and Belarus is spent on humanitarian projects58.

The Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) member states such as Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan also comprise of the top priority in Russian public diplomacy. The integration process of EAEU has been actively developing since its creation on January 1, 2015. In 2018, Russia assumed the chairmanship of the EAEU bodies and has offered an ambitious humanitarian agenda. It proposes new humanitarian initiatives and projects: the formation of a common digital space for the Union and the increase in links among the five countries in the field of nuclear energy, renewable energy sources, the environment, medicine, space exploration, tourism, and sports. It pursues a more spot-on use of the financial resources of the Eurasian Development Bank and the Eurasian Stabilization and Development Fund in order to finance intergovernmental projects. These were not originally part of the integration agenda, but, in the modern world, it is hard to imagine sustained economic development without cooperation in these areas59. While this Moscow initiative of a high integrative effect finds understanding in Minsk, it does not meet such a warm welcome in Astana, which views the EAEU as mainly for economic integration structure. Still, according to Sergei Shukhno, Director of the Department for the Development of Integration, the Eurasian Economic Commission’s humanitarian agenda is supported more and more by the scientific and expert community of the member states of the Union. For example, in April 2016, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed between the leading universities of the member states of the Union for the establishment of the “Eurasian Network University”60. As it is mentioned by Kazakhstan scholar Chokan Laumullin, the key task of EAEU countries is creating joint scientific centers for advanced studies61. Thus, the prospects of including a humanitarian component into the integration process are on the agenda, but are under question in the discussion of the expert communities and the decision-makers of the five member countries. Still, a serious problem for the PD and humanitarian cooperation of Eurasian states is that administrative structures have enough resources for international cooperation, while academic institutions are facing a lack of finances.

Another priority PD area is The Greater Eurasia – a flexible integration platform with the involvement of the members of the Eurasian Economic Union [EAEU], the Shanghai Cooperation Organization [SCO], and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations [ASEAN62]. Russian foreign policy doctrine also says about the prospects of the commin humanitarian space with EU: from the Atlantic to the Pacific63.

But regardless of the great amount of these integration projects we can assume that given its foreign policy priority, the Eurasian region is crucially important for Russian PD and humanitarian cooperation initiatives. These are realized through various programmes and institutions. Additionally, a substantial part of Russian foreign aid goes to this region through the Russia-UNDP Partnership.

Table 1: Examples of Programmes and Projects Financed by the Russian Federation in the Eurasian Region

| Comprehensive development of Naryn Oblast in Kyrgyzstan | US$3.5 million | 2014-2016 |

| Livelihood Improvement of Rural Population in Nine Districts of Tajikistan | US$6.7 million | 2014-2017 |

| Assisting the Government of the Republic of Belarus in accession to WTO (the fourth phase) | US$589,680 | 2014-2017 |

| Socio-economic development of uranium tailing communities in Kyrgyzstan | US$ 1.476 million | 2015-2016 |

| Integrated support to rural development: building resilient communities in Tavush region, Armenia | US$5 million | 2015-2020 |

| Building national capacities for establishing animal’s identification and tracking in Kyrgyzstan | US$450,000 | 2016 |

| Technical Support to Improve Sanitary, Phytosanitary, and Veterinary Safety, Including the Work towards Kyrgyzstan’s Accession to the Customs Union | $175,000 | 2014-2015 |

| Sanitary and Phyto-sanitary measures of the Republic of Tajikistan | $50,000 | 2015 |

| Capacity building of professionals of the Kyrgyz Republic for the organization of the system of cattle identification and tracing in Kyrgyzstan in the framework of participation in the Eurasian Economic Union | $449,850 | 2016 |

Source: Russia – UNDP Partnership. http://www.eurasia.undp.org/content/rbec/en/home/about_us/partners/russia-undp-partnership.html

Still, we should highlight several problems that Russian PD is dealing in the region. First of all, we are witnessing insufficient strategic advising and capacity building in crucial areas. Russia focuses on the general public or politicians, demonstrating disrespect for the young elites, while it is actively engaged by Western and Chineses public diplomacy institutions. Years later to-be political and business leaders not involved in Russian PD programmes can be not interested in political and economic cooperation of Russia and their states.

Secondly, some Russian initiatives in the region are very disputable. Russia is seen to be fond of establishing monuments rather than going to the universities of its partner states.

Thirdly, Russian strategic asset in the region – Russian language – suffers because of some bureaucratic mistakes. The title of the key foundation promoting Russian language ‘Russkiy Mir’ (Russian World/Russia Peace) holds a negative connotation in its neighboring countries (we can imagine how the American English-language promoting structure ‘Pax Americana’ would be perceived in Mexico). It was created in addition to the world recognized Pushkin State Russian Language Institute (Pushkin Institute) founded by the USSR in 1966 and has 300,000 alumni only in Cuba.

And finally, we are often witnessing an “inside-out” not “outside-in” approach: the actions in this sphere are taken according to the way Russians think foreign “movers and shakers” see them, not the way they really perceive it. Russian economic weakness endangers its attractiveness and PD efforts. Its brands are not as successful as the Western or Chinese ones. An example of this is seen with the Russian brand Sberbank (with the state participation) which costs about nine billion dollars, while the strongest US brand, Google (the private one), is evaluated about $109 billion64. So, the “Kitchen debate” (1950-s Rusisa-US industrial competition during joint cultural exchanges) for hearts and minds of citizens of Eurasian countries possibly would not be in favor of Russia and that endangers seriously PD efforts in the crucial area.

Despite the fact that the priority region for the implementation of PD programs is Eurasia, the Russian activities in this field are global and include assistance to the Sub-Saharan countries of Africa, the poorest countries in the framework of the Asia-Pacific integration structures, and the development of cooperation with the Middle East, North Africa, and Latin America. The main recipients of Russian aid are Iraq, Jordan, Kenya, Namibia, North Korea, Palestinian Autonomy. Also, there are nations that are currently affected by armed conflicts, including Yemen, Somalia, South Sudan, and parts of Nigeria facing a problem with famine. Over the past four years, Russia has allocated about eight million dollars in aid to these countries and helped to deliver one-hundred and ten tons of humanitarian cargo to Yemen. Besides, Russia is currently actively involved with humanitarian assistance to Syria65.

Table 2: Examples of Russian-UNDP Projects in Various Geographic Regions

| UNDP part of Syria SHARP Appeal | $2 million | 2013 |

| UNDP part of the Philippines appeal | $1 million | 2013 |

| Post-hurricane recovery in Cuba | $1 million | 2014 |

| Vanuatu Debris Clearance Initiative | $0.5 million | 2015 |

| Emergency support to strengthen the resilience of the Syrian people and foster the recovery of disrupted livelihoods | $2 million | 2015 |

Source: Russia – UNDP Partnership. http://www.eurasia.undp.org/content/rbec/en/home/about_us/partners/russia-undp-partnership.html

PD and humanitarian cooperation are critical in times of growing confrontation as far as it promotes dialogue. Even when it seems that it’s impossible to make it worser Russian-Western relationships deteriorate from date to date. In the beginning of the 1990s it seemed that history had ended and the world was going to dive into an era of global prosperity. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the end of the Cold War, the Russian-Western relationship took on a new dimension with Russia trying to integrate into Western structures.’The deterioration of Russian-Western relations escalated with the 1994 Chechen War, NATO intervention in Serbia following the civil war in the Balkans. It reached a critical level with Russia’s relations with Georgia/South Ossetia, expansion of NATO to Eastern European states, relinquishment of Crimea to Russia, So, the new Cold War thinking has prevailed and now it would be too difficult to chart a new roadmap, as it will take decades to erode mistrust on both sides. PD could be one of the main instruments in it. Our countries are dealing with international crises either as participants or peace-makers, and since we are facing the growth of conflicts worldwide it can be an essential tool of the public diplomacy to handle it and deascalate the situation, solve conlicts instead of managing it. As it was told by Doctor Henry Kissinger while his Primakov lection at the Gorchakov Fund “Today threats more frequently arise from the disintegration of state power and the growing number of ungoverned territories. This spreading power vacuum cannot be dealt with by any state, no matter how powerful on an exclusively national basis. It requires sustained cooperation between the United States and Russia, and other major powers ”66.

So, what could be done to improve our relations? Although there is no remedy, it seems like public diplomacy (and even P2P) initiatives would be very timely to deescalate global disarray. History proves that détente talks had started in the period of most serious confrontation in the 1970s. Similar public diplomacy and humanitarian cooperation tools should be implemented.

Russia positioning itself as the great power is interested in having partners “Interested in dialogue” all over the world. To foster its international dialogue, it widely uses PD and humanitarian cooperation instruments. Therefore Rossotrudnichestvo Agency is represented in eighty countries. More focus is shifted towards PD dialogue with the emerging Asian countries, as well as with BRICS and MINT countries. Russia actively participates in interesting formats, has strong allies, namely in frames of BRICS, it is the initiator or member of the Think-Tank Council, the Academic Forum, the Civil BRICS Forum, the Young Diplomats Forum, the Youth Summit and the Young Scientists Forum, the BRICS Women’s Forum, and the BRICS Women’s Business Alliance67. A personalized approach and interaction with all those willing to listen is quite necessary, as is the “two-way” communication with the target audience that is interested in having a conversation, rather than just receiving messages.

So, we can assume that Russian PD and humanitarian cooperation are aimed to support sustained social and economic growth within its partner states and to find a solution for global and regional problems contributing to stability and security in the system of international relations.

Conclusions

Nowadays, a lot of countries are dealing with international crises either as participants or peace-makers, and since we are facing the growth of conflicts worldwide, PD is becoming a more and more needed instrument capable of laying the ground for international cooperation and promoting international agenda. Public diplomacy initiatives, interconnected with the Track II diplomacy, can be very timely to prevent global confrontation that we are witnessing nowadays.

Russian public diplomacy and humanitarian cooperation are focused on the Eurasian region, as well as on the countries disillusioned with the West, searching for a new joint international agenda, countering Western hegemony on setting universal values (mainly liberal one). Also it is used as the Track II instrument to prevent escalation of the situation with the strategic partners.

Russian approach towards public diplomacy differs from the Western one appealing to the human rights agenda, democratization, transparency and the rule of law. Undoubdtedly, a set of rights like free speech, the freedom of peaceful assembly, of religion, equality for men and women under the rule of law is universal. But Russia would not agree that values prevail over national interests. Destabilisation of the vast regions through regyme change practice prove this message. It is seen in Russia that while non-Western countries are supposed to be focused on these factors, Western public diplomacy promotes own the national interests and foreign policy goals. Russian PD has found its own approach towards foreign audience disillusioned with Western practices of coercive democratiosation, regyme change and humanitarian interventionism. Russia is seen by this audience as a protector of the free world and traditional family values.

In the digital age, Russia is trying to find the right solution for making Edmund Gullion’s “the last three feet” approach towards the foreign audience (seen as people who are or will be close to the decision-making and agenda-setting process) while branding itself as attractive, credible, open-minded, and conducting dialogue rather than monologue. It uses PD and humanitarian cooperation tools for succeeding in it. Still, it should strive to be leader in technology, the economy and knowledge.

The Russian experience is unique to some extent. The country was a PD superpower since the 1917 Revolution (here we can remember the first woman ambassador Alexandra Kollontai), attracting the minds of the rest of the world until the beginning of the 1990s. Nowadays the main treasure of Russia is its people and its geography – that is why using PD while branding various Russian regions, launching new tourism programs and substate diplomacy initiatives could contribute a lot towards Russia being associated not only with “balalaika” and “vodka”, but with Tomsk University, Karelian resort or Baikal omul. Nowadays Russian PD and humanitarian cooperation are becoming increasingly important to effectively promote a positive, balanced, and unifying international agenda. This experience, somewhere successful, somewhere hard, undoubtedly deserves to be studied and analysed by Russian as well as foreign scholars and practitioners.

Notes

References

Borishpoletz, K.P., 2016, ‘Public diplomacy in EEU region: understanding the phenomenon and its development’. MGIMO Journal, 5 (44), 2015, 42-55.

Lukin, A.V., ‘Rossijskaya publichnaya diplomatiya’. International Affairs Journal, 3, 2013, 27 – 35.

Kozyrev, V., ‘Soviet Policy Toward the United States and China, 1969–1979’, in Kirby, W.C. (Ed.), Normalizing U.S.-China relations. An International history, Harvard East Asian monographs, pp. 180-195.

Lebedeva, O.V. ‘Istoriya vozniknoveniya instituta publichnoj diplomatii v Rossii’. International Affairs Journal, 2, 2016, pp. 126-146.

Lebedeva, O.V. ‘Kul’turnaya diplomatiya kak instrument vneshnej politiki Rossii na sovremennom ehtape’. International Affairs Journal, 9, 2016, pp. 76-97.

Osipova,Y., October 2015, ‘US-Russia Relations in the Context of Cold War 2.0: Attitudes, Approaches, and the Potential of PublicDiplomary’, in Albright, A., Bachiyska, K., Martin, L. & Osipova, Y., eds., Beyond Cold-War Thinking:Young Perspectives on US-Russia Relations,Washington, DC: Centre on Global Interests, pp.41-5

Ponomareva, E.G., ‘Russian Public diplomacy in the Balkans: problems and prospects’. Vneshnepoliticheskie interesy Rossii: istoriya i soveremennost’.Cbornik materialov IV Povolzhskogo nauchnogo kongressa. Samarskaya gumanitarnaya akademiya. 2017. pp. 172-181.

Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MID), 2016, 1 December, Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation, Approved by President of the Russian Federation V.Putin on 30 November 2016, Document no.2232- 01-12-2016. www.mid.ru/en/foreignpolicy/official_documents/-/asset publisher/CptICkB6BZ29/ content/id/2542248.

Samoilenko, S.A., ‘Crisis communication research in Russia. Case studies’. http://www.academia.edu/19568540/CRISIS_COMMUNICATION_RESEARCH_IN_RUSSIA._CASE_STUDIES.

Semedov, S.A. (Ed.), ‘Mezhdunarodnoe sotrudnichestvo v usloviyah globalizacii’ /pod red. S. A. Semedova. Izdatel’skii dom «Delo» RANHiGS, 2018. – 390 p.

Simons, G., ‘Media and Public Diplomacy’, in Tsygankov, A. (Ed.) Routledge handbook of Russian Foreign Policy, Routledge, pp. 199 – 217.

Tsvetkova, N.A, 2016, ‘New Forms and Elements of US Public Diplomacy’. International Trends, 13(3), pp. 121-133.

Tsvetkova, N., 2017, ‘Soft Power and Public Diplomacy’, in Tsvetkova, N. (Ed.), Russia and the World: Understanding International Relations. Lanham, Boulder, New York, London: Roman & Littlefield, 2017, pp. 231–251.

Velikaya, A.A. ‘Public diplomacy and Humanitarian cooperation in the context of modern international trends’, in Panov A., Lebedeva O. Public diplomacy of foreign states, Aspekt-Press, 2018. [Publichnaya diplomatiya zarubezhnyh stran. Pod red. A. Panova, O.Lebedevoj. Aspekt-press, 2018].

Velikaya, A.A., ‘Russian–U.S. public diplomacy dialogue: a view from Moscow’, Place Branding and Public Diplomacy (2018), pp. 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-018-0102-1.

Zonova, T.V.,‘Public diplomacy and its actors‘. http://russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-and-comments/analytics/public-diplomacy-and-its-actors, 22 August 2012.

Zonova, T.V., ‘Will NGOs survive in the Future?’, 16 November 2013, Russia in Global Affairs, http://eng.globalaffairs.ru/book/Will-NGOs-Survive-In-the-Future-16202.