China vs. the West: An Analysis of the Current Geoeconomic Tug Of War

The Dragon is awakening, and the world is trembling

The Dragon woke up making the whole world tremble. Nothing shakes China, not even the 2008 financial crisis during which its model was seen as an alternative model savior. China continues to display insolent growth and impudent arrogance. China’s success challenges and fuels many curiosities. Indeed, here is a Confucian state, which is not formally a Western liberal democracy, officially communist, that has become the second largest economic power in the world in just three decades! The country has experienced a surging leap with China’s accession to the WTO and thanks to the government’s “Go Out Policy” strategy, a real catalyst to Chinese companies.

However, it is not easy to describe precisely what China’s opening up to the rest of the world in 1979 is really about. It took almost 30 years of internationalization for researchers to explain a little bit more accurately the outline of the nation-state of China. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has shown its capacity for adaptation and modernization through a series of reforms accompanying the progress of its industrialization. China was both cautious and rational following in this Confucius teachings, empiricist and opportunist like the West and, finally, secretive as taught by Sun Tzu.

During the 2008 crisis, China was not shaken by the debacle of the Anglo-Saxon financial system, thus revealing the strength of its management system, all the more reinforced when it was solicited by the G20 (of which it is a member) to play a decisive role in the global economic recovery. But nearly a decade later, Trump happened and rien ne va plus! The global geopolitical landscape experienced and is still undergoing a cosmic seism at all levels. Its latest effect is the trade war between the U.S. and China. Why is Trump the businessman first and foremost so adamant about attacking China? What is he afraid of?

To answer these questions, a look back into history and a shift from geopolitics to geoeconomics and geostrategy are mandatory to understand what is happening and what is at stake.

China’s transformation from a nation-civilization state to a holding state

A relationship between China’s economic success and the strategies adopted since its opening up to the world exists. Hence, it is essential to focus on the internationalization strategies of Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOE), the first Chinese companies that got into the global market. And since trade is the sinews of war, it is crucial to understand how they got there.

I assume that the strategies developed by Chinese companies are related to the stages of internationalization of enterprises in general. The Chinese company, like any business, has a date of birth, must grow and develop and, if necessary, reproduce itself. Growth, development, and reproduction have required and still require a strategy or a series of strategies set by the PRC’s plans. It is certain that a well-developed company with a potential projection to go abroad is the ideal candidate for internationalization.

The development plan holds on to all companies considered by the PRC as necessary to meet its socio-economic objectives as new battle horses. Since they are state-owned enterprises, their particular strategy is part of another higher-level strategy, that of the state. What is striking is that research that focuses on Chinese SOE strategies most of the time conceals the PRC’s parent strategy! SOEs have strategies derived from a parent strategy, and that must never be forgotten! SOEs are therefore instruments of economic and social policy whose primary function is to achieve strategic goals set in advance within the framework of the plan. In doing so, SOEs appear as companies of a vast holding enterprise called the PRC and whose management is the responsibility of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), a huge holding company operating in all sectors of activity.

The state here is considered as a company obeying the Weberian definition1:

- A modern state is a system of administration and law that is modified by state and law and which guides the collective actions of the executive staff.

- The executive is regulated by statute likewise and claims authority over members of the association (those who necessarily belong to the association by birth) but within a broader scope overall actively taking place in the territory over which it exercises domination.

- Its characteristics are territoriality, state monopoly on violence, and legitimacy.

On the difficulty of studying emerging markets in general and China in particular

Analyzing emerging markets is venturing into unchartered territories whose only reference is the knowledge available in mature Western markets. Current Western theories are unable to fully explain what is happening in emerging economies whose contexts are dynamic and where adaptation is not easy. And when these theories are applied to China, the results are even more uncertain.

Indeed, researchers, experts, and analysts need to continually adapt their knowledge and be ready to let go of a good deal (if not all) of the Western theories or tactics/strategies that have been successful in mature markets since the theories studied today at universities and think tanks are theories that have been established in mature markets a posteriori (with hindsight and after long periods of observation and reflection) in Western capitalist organizations.

That said, China is an emerging, dynamic market that is continuously evolving. Its organizations are not capitalist (a mixture of communism, socialism and controlled capitalism). Moreover, China is a country in the Far East, far from the West and its ways. Some researchers tend to forget to be aware of these differences. They mostly analyze and comment on China and its geopolitics/geostrategy/geoeconomics with a Western point of view. This often shows a lack of knowledge of the Middle Kingdom, and it is sometimes laughable.

China’s two-faced strategy: Sun Tzu and Confucius in action

According to the spirit of Sun Tzu, the strategy of the Chinese state includes two aspects, one visible and one hidden, like yin and yang. The visible aspect is not the strategies, secretive in their nature (Sun Tzu), but the results of a series of strategies implemented cautiously by the CCP (the fear of not succeeding, small steps and trial-and-error methods according to Confucius) and applied by Chinese companies.

These results must be spectacularly positive (e.g., changes in GDP and exports) or negative (e.g., the accident of the Chinese high-speed train in 2011 which questioned the safety of the railways of which China is a great manufacturer) to attract the attention of the foreign observer. From success or failure, strategies and their implementation steps can be reconstructed to understand and learn from them. It is an ex-post reconstruction process that requires adequate conceptual tools to understand China’s internationalization through its SOEs, a phenomenon (part of globalization) that is induced or that occurred in imitation of what is happening in mature Western markets.

Since Chinese multinationals are recent and have only emerged after China’s cautious opening to the rest of the world and after a series of reforms leading to its WTO membership, it is then essential to recall the history of the waves of internationalization to understand better the general context, including geographic, historical and economic aspects.

China’s internationalization stages interlocking with the West’s waves of internationalization

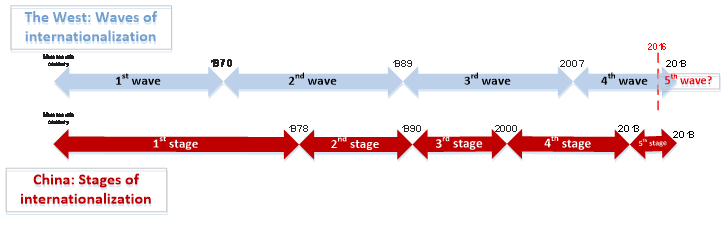

Based on my research, there are four waves of internationalization instead of the commonly found three2 because the global geopolitical landscape has changed since the 2008 financial crisis.

The first wave (nineteenth century – 1970) encompasses the Western world whose market is mature; characterized, among other things, by the non-intervention of the State. The world has seen the rise and the fall of the colonial empires, the 1929 economic crisis as well as the Bretton Woods system, and the two world wars followed by the Thirty Glorious Years (the long post-war boom). During this wave, the first Western multinationals appeared in North America and Western Europe.

The second wave (1971 – 1989) was born with the emergence of two alternative capitalist models to the dominant West: that of Japan first and that of South Korea later. These countries, following the logic of the Western-style market economy with a Far-Eastern touch, resort to state intervention/dirigisme since they follow the social-democratic movement. During this wave, the European Economic Community emerged while the U.S. model began to show signs of running out of steam in the early 1980s. At the same time, Western multinationals started penetrating the East Asian market.

The third wave (1990 – 2007) was marked by the collapse of the Soviet bloc and the opening to the market economy of formerly communist countries with planned economies, which made them turbulent, risky and uncertain. This wave has known two flows. On the one hand, internationalization is no longer the sole privilege of Western multinationals, but also of SMEs that have established themselves in the shadow of multinational corporations. This flow to emerging markets has shown the shift of competition in mature Western markets to emerging markets. Western multinationals started settling in China, India, Central and Eastern Europe and Russia. On the other hand, there is a flow from emerging markets to mature markets, and this is what started fueling the West’s fears, since the latter felt that it was no longer dominating the global landscape. The West was and is fearful of an Asian tidal wave surging on its market, in particular the “yellow peril” of Chinese SMEs waiting to invade the European market.

The fourth wave (2008 – the present day) began with the global financial crisis that has seen companies and even countries being bankrupt at a large scale, a crisis that showed the limits of the American liberal system while alternative models from the emerging economies arose. The European Union has been dragged from one crisis to another, the latest being Brexit and the Catalan issue. Meanwhile, other countries’ associations such as the BRICS emerged. The final straw was the election of Donald J. Trump as the 45th president of the U.S. This wave has and is currently knowing an erosion of all the gains of the twentieth century with regards to democracy, freedom of the press, human rights… Global organizations such as NATO and the UN are bogged down in an internal crisis which is not boding well for their future. Wars and conflicts are now being shifted to cyberspace, which both amplifies and complicates them. The globalization acceleration in this wave has created fears of all types that have manifested themselves in the rise of protectionism, rise of authoritarianism, and rise of nationalism.

The main characteristic of this wave can be summarized in two words: crisis and disruption in the global political and economic landscape at all levels. If Trump is reelected, this wave may be stopped at 2016, and a fifth wave will emerge starting in 2017 since his election has created a schism in the global landscape and is a turning point in global history. Time will tell.

What about China’s case? From the nineteenth century to the present day, China’s economy is still experiencing a transitional phase due to the pace of growth accompanied by ever-changing institutional reforms. The internationalization of Chinese companies includes steps that go along with the waves above. Based on my research, there are five stages of internationalization instead of the commonly found three3: I have added an embryonic stage that is a premodern stage and the last stage related to the advent of Xi Jinping as the 7th President of the PRC.

The premodern embryonic stage (nineteenth century – 1978): generally the first wave of internationalization. During this stage, China experienced several milestone events, from exchanges with foreigners settled in the coastal zone (e.g., Hong Kong, Macao…) with France, Great Britain, Germany, the Netherlands and Russia to humiliations during the opium wars to the defeat in the hands of the Japanese and the loss of Taiwan to Japan. The abolition of the Empire followed, and the Republic was established. Inner wars between communists and nationalists followed until the victory of the Communists in 1949.

Under Mao Zedong’s rule, China shut itself up in socialist utopia with the communist bloc and made a more or less successful first attempt of massive industrialization. The first joint venture took place with the transposition of the Russian communist model in China via the CCP, a creation of the former USSR.

China experienced the transition from a premodern economy based, among other things, on the sale of tea, silk, and ceramics, to a planned economy based, among others, on barter. Launched with the slogan “Catching England in 15 years” in 1958, the “Great Leap Forward” has given catastrophic results.

The first stage (1978 – 1990): the second wave of internationalization. China was cautiously opening up to the world thanks to Deng Xiaoping’s policies and the Equity Joint Venture Law passed in July 1979 after the disastrous Cultural Revolution. This law allowed 1) the formation of joint ventures, 2) the penetration of foreign capital, 3) the penetration of Western multinationals into China, and 4) the beginning of the export of Chinese goods manufactured for Westerners. The first international business activities began, and Chinese SMEs benefited from their 1979 Joint Venture Law. China entered the school of the world.

China wanted to create foreign exchange based on its most abundant and cheapest factor (labor) through foreign capital and know-how. In fact, the combination of cheap labor and the employment of a large labor force by foreign investment became the starting point for decades of growth (in economic terms, this amounts to the expression of the theorem of Heckscher). Following the guidelines of the State Development and Reform Commission, Chinese companies, regardless of their sector of activity, focused their efforts on acquiring the knowledge and technology of foreigners through established joint ventures. Intensive indirect exports marked this period, which was a preliminary test period with a cautious opening to the world following in this Confucius teachings.

The second stage (1991 – 2000): the third wave of internationalization. Large state-owned Chinese enterprises were allowed to invest abroad and participate in the game of takeover bids and cross-border mergers and acquisitions through new policies and government reforms. Chinese companies seized the opportunity to invest, buy and merge with Western companies. Chinese SMEs continued to take advantage of these golden opportunities while large multinationals were slowly forming in the domestic market. China continued to be in the school of the world while transitioning to the market economy.

However, while continuing to learn from foreigners, Chinese companies were moving to another stage of government direction, namely the development of Chinese intellectual property and industrial property products. Direct exports were beginning to invade the global market.

The third stage (2000 – 2013): the third and fourth waves of internationalization. This stage began with the implementation of the Going Global Strategy (Go Out Policy) decided in 1999 by the Chinese government. The success of the CCP’s reforms and sustained economic growth led to China’s entry into the WTO, which has allowed, among other things, the massive and free entry of foreign capital. The policies of the State Commission for Development and Reform became more precise and more explicit, and their results were spectacular. For example, there are more and more dragons in the Fortune 500 ranking. Internationalization took many forms that the West, taken by surprise, was and is still discovering.

Moreover, China was moving up a gear: it was conquering the world in several sectors. The parent strategy encompassing all government directives to control the national and international context continued to be followed by a change in the stage of development. Indeed, Chinese companies were gradually leaving behind joint ventures to become more and more independent to reach, possibly in the near future (the last stage of the state’s guidelines), Chinese domination in China and all over the world.

In addition to exports (direct and indirect), Chinese subsidiaries/franchises started appearing in various countries. Chinese multinationals continued and are continuing the global landscape invasion at the expense of Western and Japanese companies, as evidenced by the Fortune 500 annual ranking.

The fourth stage (2013 – the present day): the fourth wave of internationalization. The primary catalyst of this stage is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that took over the whole world with its various facets: the Silk Road Economic Belt, the Maritime Silk Road, and the Polar Silk Road. The BRI is the realization of the conquest of space at the expense mainly of the EU and Russia on the one hand and the gradual indirect sinicization of the countries with which it is in contact (soft power) on the other hand.

In the name of enhancing regional connectivity, China started waving webs all over the world. Meanwhile, trade, energy, and security remain crucial. With China being the world’s first currency reserve and the world’s second economic power despite being non-Western, non-fully-capitalist and non-democratic, the West seems helpless facing this giant holding-state and feels threatened by its power, as it is not easy to know where China really stands and what its modus operandi is. It is a situation that Trump felt, hence his “Make America Great Again” and his current trade war with China.

The West’s disarrayed answer to China’s dominating and threatening rise

The West realized too late that the Middle Kingdom has woken up and has become an economic power, a key player in the global landscape. China the holding-state went beyond the Weberian definition of the state (territoriality, state monopoly on violence, and legitimacy) by taking care of the economic, military, and social spheres. The objective of China’s parent strategy has become clear: global economic domination via trade and finance using the BRI. The image of this colossus having its tentacles everywhere disturbs the West – it has never had to deal with a competitor of this size and this nature.

In general, the West blames China for not respecting the conditions of free competition, that is to say, that the state should not interfere in the activities of companies; China must not play the puppeteer and be the crutch of companies in order to meet, in the long run, its strategic goal.

On the one side, there is the American reaction to China’s rise. Indeed, Trump does not consider China as its fair economic competitor but as a hegemonic threat: Whoever wants to put down his dog blames it on rabies! Trump started his trade war with China with his attacks, his sanctions, and his tweets. He is confrontational because he feels that the U.S. will be outpaced in the commercial sphere by China.

The American smear campaign is broadly reminiscent (to a certain extent) of the Japan-bashing campaign during the 1980s when analysts used to predict that Japan would soon dethrone the U.S. But China is not Japan, and the context of the 1980s is not the same as today. The rules of the game have changed. Trump has an epidermal and emotional reaction, far from the more thoughtful, comprehensive responses of any experienced diplomat. Trump thinks first and foremost of financial gain and ignores respect for values such as peace and international security. Trump rejects the approach established by international conventions (e.g., WTO) and prefers protectionism instead. He becomes judge and jury, while it is the WTO that must settle this case.

On the other side, there is the European reaction to China’s rise. Even though the EU is experiencing internal issues, when it comes to China, the EU is smarter than Trump’s America. The EU does not feel threatened by the Chinese hegemony comparing to the U.S. The EU is trying to respond by taking into consideration the historical conditions of China, something that was done by the U.S. until the advent of Trump.

The EU is opportunistic. Indeed, the EU sees opportunities to penetrate the Chinese market, an untapped market to conquer more than a billion consumers, which is an unexpected windfall in these times of global economic competition! Working ‘collaboratively’ with China to do business while juggling China’s demands, trying to have win-win deals while setting aside the protectionist Trump’s U.S. is an attractive goal.

In conclusion, between the American reaction, which is part of a short-term tactical response, and the European response that is part of a long-term diplomatic strategic response, China is facing a disunited West while international relations are suffering the counter-blows. Westerners are hit hard by what they call China’s overcapacity, when everything is relative. Indeed, when a Chinese SOE is working for the domestic market, it has already achieved returns on a scale that allows it to supply the rest of the world. That level of scale is what Trump does not grasp, even as the Europeans began to understand and grapple with it. Current economic theories have reached their limits in the face of the holding-state that is the Chinese colossus.

What solution could appease these ailing international relations between the West and China?

Whether the West or China, both must move towards the other to clear the air and to have healthier international relations. The solution revolves around three axes: knowledge, know-how-to-be and know-how.

On the one hand, firstly, the West must understand China, its history, its millennial culture, its modus operandi and its South Asian mode of production (already explained by Karl Marx) to avoid making snap judgments and analyses that miss the point entirely. Secondly, the West must accept that China has become the second economic power in the world, a power that is neither Western, nor democratic, nor thoroughly capitalist, and stop patronizing it. Finally, if there are conflicts, international organizations must be involved to help resolve them (e.g., WTO, UNSC). This will help to frame international relations on the path to a healthy balance and avoid unnecessarily expensive escalations in time, money and energy.

On the other hand, China too has to move towards the West. Firstly, China must also understand the West, its history, culture and modus operandi. Secondly, China must listen to the West and its grievances about the various issues where they clash. Finally, at the domestic level, China must accelerate the evolution of its reforms while, at the international level, it must keep its promises to accommodate and respond to the Western countries’ concerns. It is crucial to avoid falling into the Talion Law, and to place more trust in international organizations.

Finally, whether it is the West or China, applying these solutions will not be easy, and, in some cases, personal interests may take precedence over the rest, with each country and each leader having their respective agendas. Emotions, demagogic and populist speeches do not have their place in the current muddy global geopolitical chessboard. However, with some goodwill from everyone, each side could move towards the other, and the world will be better… at least we hope that will be the case, but we will have to wait and see.

Notes

References

ANTER, Andreas (2014). Max Weber’s Theory of the Modern State: Origins, structure and Significance, Springer, 249 p.

ER-RAFIA, Fatima-Zohra (2012). Les stratégies d’internationalisation des entreprises étatiques chinoises (Internationalization Strategies of Chinese State-Owned Enterprises), paper presented in Lyon (France), the second Edition of the Francophone Association of International Management.

ER-RAFIA, Fatima-Zohra (2015). Is China the New Japan of the 21st Century?, doctoral thesis, 670 p.

JANSSON, Hans (2007 a). International Business Strategy in Emerging Country Markets – The Institutional Network Approach, Cornwall, Edward Elgar Publishing, 286 p.

JANSSON, Hans (2007 b). International Business Marketing in Emerging Country Markets – The Third Wave of Internationalization of Firms, Cornwall, Edward Elgar Publishing, 238 p.

PLAFKER, Ted. (2007). Doing Business in China, NY: WBB, 292 p.

SÖDERMAN, Sten, Anders JAKOBSSON and Luis SOLER (2008). «A Quest for Repositioning: The Emerging Internationalization of Chinese Companies», Asian Business & Management, 7, pp. 115-142.

YANG, Xiaohua, Yi JIANG, Rongping KANG and Yinbin KE (2009). «A Comparative analysis of the internationalization of Chinese and Japanese firms», Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 26, pp. 141-162.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence.