Trapped in Proto-Bipolarism? Brazilian Perceptions of an Emerging Chinese-American Rivalry

Download this article in PDF formatAbstract

With the use of recent survey data, we empirically test a simple proposition that has strong impacts in terms of policymaking, both in Brazil and China: that the more Brazilians become aware of a post-hegemonic scenario in which the United States loses pre-eminence, the more China will be able to sell itself as a trustworthy partner. Although only 36 percent of Brazilians feel China is such a trustworthy partner, those who prefer a scenario in which China surpasses the United States economically have odds between 2.5 and 3.5 higher of trusting China. Brazilians, we believe, will reshape their opinion towards China gradually, as Chinese economic statecraft “wins hearts and minds”.

Keywords

Introduction

In the first article of this special issue, Ambassador Antonio Patriota raised the question of the international system being ready for a competitive multipolar order. This question carries a highly important message: a changing world exhibits an array of challenges, and due to the lack of a single hegemon to provide leadership, political agendas are thus defined collectively. In this scenario, regional powers try to influence the international agenda in those specific areas in which they are able to exert a leading role. In Brazil’s case, the country plays a prominent role in poverty reduction and in the development and environmental agendas, areas where the country possesses expertise (Dauvergne & Farias 2012). However, this is not the case for many other issues.

A changing international system also makes possible the emergence of new superpowers that destabilize the world we are used to seeing. Rather than a multipolar system, in which Brazil would play an active role, we foresee a proto-bipolarism between the United States and China in which Brazil is trapped in a minor role. The rising influence exerted by China in Latin America, which is in part explained as a consequence of a vacuum of power left by the United States (Urdinez et al. 2016), is changing policies and perceptions in the region. In the aftermath of the Cold War, China’s steady ascension has heralded a new force, creating an economic and political rivalry to the United States, which was only countered by the American government — quite aggressively— when Donald Trump started campaigning for the presidency.

While Brazil might need to conform to an increasingly multipolar international system as Patriota argues, it is still also very likely, we contend, that it will have to adapt to an increasing rivalry between the strongest poles, the United States and China. Both arguments converge on one point: unipolarity, which seemed durable only a few years ago, now appears today as a “passing moment” (Schweller & Pu 2011, p.41). How would Brazilians react to such a context? We believe that a national survey carried out in 2015 by the Institute of International Relations of the University of São Paulo can give us some interpretative clues to answer this question.1

Previous work has used survey data to analyze perceptions about international issues in Brazil, some of them with regard to elites (Power & Zucco 2012), others to offer novel evidence on key historical periods (Loureiro, Guimarães & Schor 2015). Although this database has been used previously to analyze the Brazilian public opinion with respect to international affairs (Onuki, Mouron & Urdinez 2016), it has not yet been used to study the perception of Brazilians regarding the Chinese rise.

This article departs from literature that has suggested that the power distribution of the international system may lean towards bipolarism if China continues on the path of economic and military growth (Walt 2005; Paul 2005; Legro 2007; Layne 2008; Schweller & Pu 2011, to cite a few) as opposed to the literature that foresaw a multipolar scenario in which the BRIC countries would play an active role (Hurrell 2006; Brawley 2007; Zakaria 2008; Schweller 2011; Nadkarni & Noonan 2013; Acharya 2014; Stuenkel 2015). While some authors still define the current system as unipolar, they also leave the door open to a bipolar distribution in the future (Volgy & Imwalle 1995; Pape 2005; Ikenberry 2008; Ikenberry, Mastanduno & Wohlforth 2009; Walt 2009; Ikenberry 2011); this literature is also connected to our argument. This is an ongoing debate, and because no one has a crystal ball, predictions have limited value. What is certain is that China’s rise is challenging American hegemony worldwide, and that will impact Brazil domestically.

This paper aims at empirically testing a very simple proposition with strong impact in policy making both in Brazil and China: is it true that the more Brazilians become aware of a post-hegemonic scenario in which United States loses pre-eminence, the more China will be able to sell itself as a trusting partner? Put differently, the efficacy to date of Chinese economic statecraft and soft power in Latin America depends also on how much it can be seen as an alternative to American hegemony (Gill & Huang 2006; Bräutigam & Xiaoyang 2012; Reilly 2013; Urdinez et al. 2016). In this sense, the Chinese economic rise in Latin America can progressively cause a gain in the the trust of countries in the region towards the Asian giant, overcoming the barriers of the lack of political legitimacy and shared values.

We organize this article into four subsections: the first examines feelings towards the rise of China, being overall defined as having a lack of trust and being fearful, and presenting some reasons for this finding. This section is followed by an evaluation of how trust in China might be enhanced by comprehension of the increasing benefits of the potential role that China can play in global governance issues, such as global peace and the economy, vis-à-vis a US-led international economy. The last section tests our hypothesis empirically using logistic models. Our findings confirm that there is a positive association between perceiving China as a positive alternative to the United States and having more trust in China

Has the Rise of China Created Mistrust?

While its profile rises, China may arouse uncertainties regarding its disposition toward the world. Has China been confrontational toward the international community? There are, we think, two overlapping theories addressing this question by two groups of renowned authors. On the one hand, Buzan & Cox (2013) refer to rise, and to describe it, they use a 4 × 2 matrix that can be used for comparative purposes with other historical rises (see table 1). In their view, peaceful rises, “such as the Chinese, involves a two-way process in which the rising power accommodates itself to the rules and structures of international society, while at the same time other great powers accommodate some changes in those rules and structures by way of adjusting to the new disposition of power and status” (2013, p.4). There are several authors whose works fit well into this categorization, although they do not always use the same concepts to describe Chinese ascent (Qingguo 2005; Chan 2007; Yue 2008).

Table 1: Comparison of the Chinese Rise to Other Superpowers.

| Rise | Not Rise | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cold |

|

– | ||||

| Warm |

|

On the other hand, some authors define China’s diplomacy as assertive. This term can be defined as “a form of diplomacy that explicitly threatens to impose costs on another actor that are clearly higher than before” (Chen, Pu & Johnston 2014, p.176). While it is difficult to equate a rise (referring to an ascending move in the international system) with assertiveness (referring to a political attitude) both are used to describe the same phenomenon. It might be that because China is rising it behaves more assertively, for instance, but such a statement needs to be tested empirically. Authors that discuss policy recommendations for China to avoid conflict in South East Asia (particularly due to the One China Policy) can be categorized using the assertive-non-assertive matrix (Christensen 2006; Mearsheimer 2010; Glaser 2015; Harris 2015).

The Chinese rise — assertive or not — has been met with distrust by Latin American governments (Urdinez, Knoerich & Feliú Ribeiro 2016). One of the reasons could be that the guiding principles of international relations are still concentrated on American leadership (Zhao 2016) — values such as trade liberalization, non-discrimination and democracy remain the anchoring premises of most international agreements. However, Zhao, in an article published earlier in this journal, argues that the Chinese rise does not mean rivalry to the American order. His argument is that by taking a status quo option and not presenting a revisionist-revolutionary attitude to the world order, China remains in a non-rival position with respect to the values now set internationally.

Having a hierarchical and traditional political-social system, the country has had little chance of presenting itself as a global alternative order which has already embraced democratic values (Summers 2016). In this way, China reaffirms the principles of the West by concentrating its energies on taking advantage of globalization from its comparative economic capacity. As much as Chinese attitudes may not represent assertive destructive behavior toward the international order, it still does not instill confidence that it is a country that adheres fully to current values.

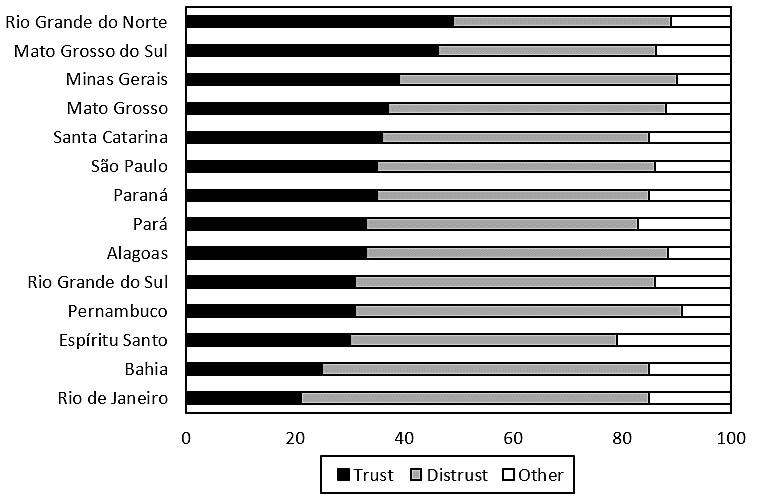

Just as the ‘good neighbor policy’ will play an important role in China’s future role as an alternative to the global order, the country will need more than economic partnerships to establish itself as a reliable ally of countries like Brazil. China still lacks soft power (Minjiang 2008), and this is highly important for Brazilian perceptions of the state. When asked about feelings toward China, Brazilians from all regions of the country tended to be suspicious of the Asian giant. The national average for those who think that China is a trustworthy partner was 36 percent. We have classified answers by federal units, and sorted them from most to least favorable.

Figure 1: Among the Following Words, Which One Best Describes Your Feelings Towards China?

Note: Elaborated by the authors. N=1881.

This question will be used as the dependent variable to understand the appeal of Chinese values among Brazilians. We have tested, in exploratory analysis, whether the differences between the federal units are due to their factor endowments or to their trade exposure to China, and we have found no evidence for these variables. Nor is there a clear geographic pattern, nor a relation with development measured in terms of GDP per capita. In section four we will include some of these variables as controls of individual perception.

Filling the Void: Chinese Ascension While American Influence Decreases.

China is filling the void left by the retreat of United States in Latin America. While the region seems to be less and less on the list of American priorities, Chinese investments and trade are opening spaces for more stable political relations.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, American hegemony in Latin America has gone through two stages, first closeness and later detachment. The first of these stages stretched from 1990 to September 11, 2001. This period was marked by the paradigm of the New World Order (Hurrell 1992) and influenced by the neoliberal thinking of the Washington Consensus, with a return of a United States presence to the politics of the Latin American region. At the same time, the period has been described as presenting a systemic configuration of unipolarity, which led Huntington to name the United States as the “lonely superpower” (1999). In Brazil, this was the era of the Real Plan, the privatization of state-owned enterprises and the increase in foreign debt, which led to widespread anti-Americanism.

The second period ran from September 11 (2001), which began with the War on Terror, was followed by the Obama Doctrine, and lasted until November 9, 2016, with the election of Donald Trump. Tulchin (2016) performs a detailed analysis of the characteristics of American hegemony throughout this period. The characteristics of US influence in Latin America, and of the power configuration of the international system, are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: US Hegemony Since 1989. US Approach Towards Latin America Regional Systemic ConfiguraitonTable 2: US Hegemony Since 1989. US Approach Towards Latin America Regional

| US Approach Towards Latin America | Regional Systemic Configuraiton | |

|---|---|---|

| New World Order | Hegemonic Order | Lonely Superpower |

| War on Terror | Retreat | Lonely Superpower |

| Obama Doctrine | Post-Hegemony | Proto-Bipolarism |

The terrorist attacks in 2001 and the militarized unilateralism favored by George W. Bush and demonstrated in the US War on Terror, destabilized the Latin American sense of community in the region, which had been experiencing a positive moment since the end of the Cold War (Tulchin 2016). According to Tulchin, “It also made the end of US hegemony more problematic. That meant that as the experience of agency in the world community became more familiar, it appeared inevitable that opposition to US hegemony would become adversarial” (2016, p.129). As the United States focused on the Middle East, the emergence of ISIS in northern Africa, and containing Russia’s aggressive foreign policy, they left Latin America as a second-class priority.

After 9/11, the United States lost interest, the budget for operations in the region was gutted, and the new regionalism initiatives from Latin America served to erode the influence of the OAS. To this came the turn to the left, which came to be known as the Pink Tide (and which brought to power political parties who were very critical of the Washington Consensus), the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) and a favorable period of high commodity prices that allowed Latin American countries to pursue an agenda of strong state investment (Campello 2015; Mares & Kacowicz 2015).

When Obama assumed the US presidency, his administration delineated a post-hegemonic policy which aimed at developing equal-to-equal relationships rather than the historically paternalistic approach of US foreign policy, which came to be known as the Obama doctrine (Drezner 2011). After the lessons of the 1990s, it was clear that despite unequaled military and economic power, and the use of that overwhelming power, the US could not guarantee specific political outcomes or protect its interests. However, populist governments would “go to extraordinary lengths to avoid following that lead and avoid US hegemonic control, even if that appears to go against their own interests” (Tulchin 2016, p.160). Furthermore, China was emerging as an alternative source of loans, investments and the main buyer of commodities filling a void left by US statecraft in the region.

Brazil’s relations with the United States illustrate this general pattern. Throughout its history, Brazilian international relations have been defined by advances and withdrawals in its relations with United States (Neto 2011; Mourón & Urdinez 2014). Despite the fact that at times the relations between countries were shaken, for example in the independent Brazilian position of non-automatic alignment during the military period, Brazil and the United States systematically maintained significant trade relations and the US has had much cultural influence over Brazilian people. Perhaps much of the ups-and-downs of the relationship with the United States were due to the constant influence of the US in the domestic foreign policy agenda of Brazil, which was seen as a limit to Brazil consolidating its own area of influence in South America (Spektor 2009).

Previous research has attempted to quantify the hegemonic influence that US exerts over Latin America. Urdinez et al. (2016) develop an American Hegemonic Influence Index to test the hypothesis that Chinese economic statecraft was stronger in countries with low scores in the index. In their rank of 21 countries in Latin America, Brazil ranked fifth for the 2013-2014 period, which denotes a ‘high’ influence. While, comparatively speaking, Brazil scores lowly in agreement with the United States on UN General Assembly votes and received American aid, it scores very high in trade dependency and received investments. Despite the apparent diminished influence in the region, United States still economically influences Brazil to a considerable extent.

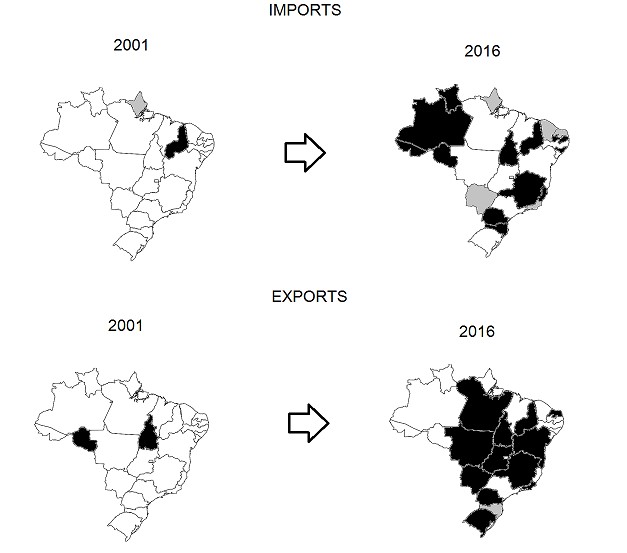

Despite the importance of the United States to economies in Latin America, the political detachment toward the region by the United States opened opportunities for the Chinese to increase their presence, mitigated by the lack of mutual values. While China steadily increased its share in the Latin American market, one of the inhibitory aspects to transforming economic power into political influence was the uncertainty of a full adherence to shared values in the region. In this sense, the United States remains, in the public imagination, the natural locus of western values. This suggests support for the view of China being limited as regards becoming a viable alternative to the American global order. The figure below shows answers to the question: ‘Which of the following countries instills in you the greatest confidence that it can keep the peace in the world?’

Figure 2: Brazilian Confidence Toward China and the US

Note: Elaborated by the authors. N=1881.

When asked about which country inspires greater confidence as regards peace-keeping, most Brazilians opted for trusting the Americans. The ratio of the US to China was, on average, 4 to 1. In this case, we attribute this finding not only to the aspects of economic dependency that these countries may represent to Brazilians but also to emotional attachment to American values. Overall, responses were consistent across the country, despite varying degrees of dependency on Chinese and American markets.

The low level of confidence seems to follow the same pattern in other areas. China also does not seem to inspire confidence in security issues, either because of Brazilian difficulty in apprehending China’s commitment to maintaining peace, or because of a Brazilian belief that China does not share similar values. It is reasonable to propose then, that Brazilians would opt for the Americans even in matters of national sovereignty, despite the historical mistrust of the American presence in the region.

Certainly, in the economic arena, China is a threat to American economic diplomacy, and this trend will remain the same for years to come. Since the end of the Cold War, the gap in the size of the two economies has been reduced by a dual process, first a slight decrease on the part of the United States and, most importantly, the solid growth of the Chinese economy, such that adding both economies together nowadays represent more than 50% of world GDP.

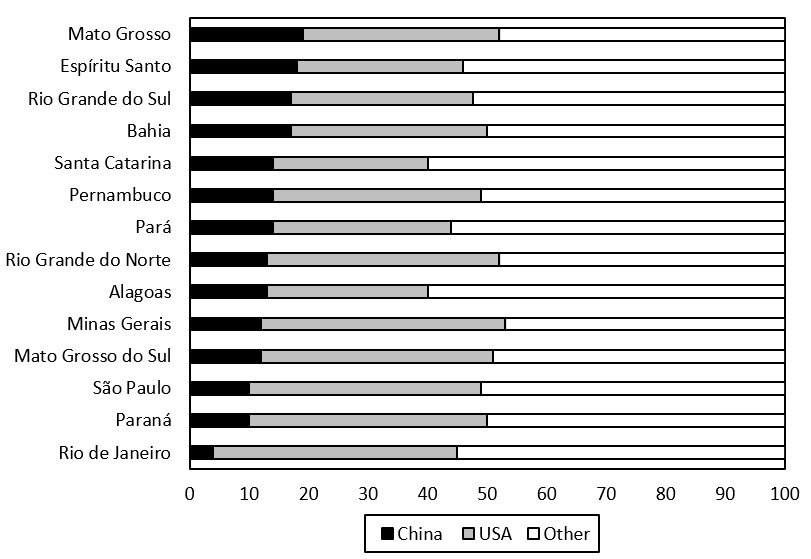

The Asian country has not only increased the degree of economic integration with developing countries through direct investment, trade and foreign aid, but also helped promote local economies by absorbing low value-added exports, primarily agricultural commodities. Chinese demand has driven Latin American economy to a period of abundance. This phenomenon was known as the Commodity Boom (Ferchen 2011), which in Brazil was one of the main sources of it´s accelerated economic growth during the first decade of the 2000s and as such received major media attention. On the other hand, Chinese growth led to a loss of competitivity in the industrial sector, which suffered from cheap Chinese imports (Urdinez 2014). It was not by chance that Brazil challenged the Chinese several times in the WTO dispute settlement body, and enforced protectionist measures in defense of national industry. Since 2001, both imports and exports grew exponentially, creating opportunities and tensions (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Trade Relations with China.

Note: States are colored black when China is the main trade partner, in gray when China is the secondary trade partner. Source: MDIC.

If on the one hand trade and investments boost the relations between China and Latin American countries, in the international arena, Brazil and China compete in investment and political influence in certain regions. With China expanding its investments and foreign aid to the Portuguese-speaking countries of Africa, the Brazilian response was to facilitate the internationalization of domestic companies through competitive loans guaranteed by the National Development Bank (BNDES) and the expansion of programs of international cooperation for development (Rodrigues & Gonçalves 2016; Mouron, Urdinez & Schenoni 2016). Being strategic for Brazilian international purposes, those regions represent locations where conflicts of interests emerge.

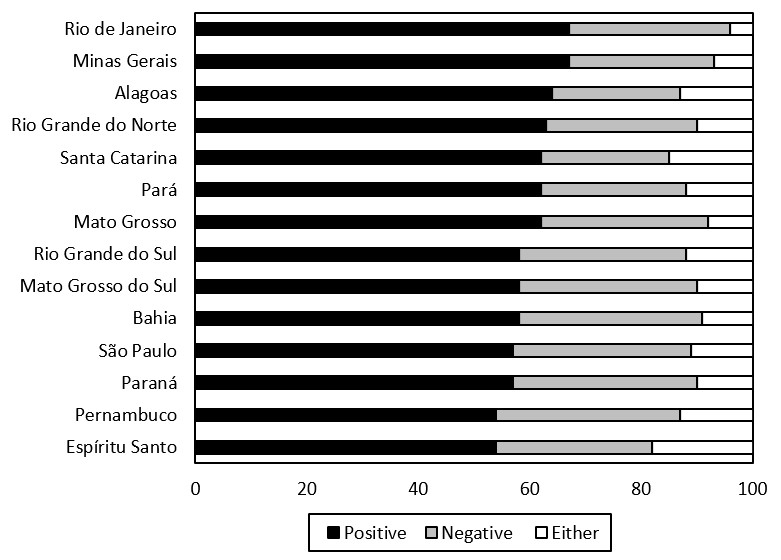

Although we have observed that Brazilians prefer the US to China when it comes to keeping international peace and that there are disputes for regional influence between Brazil and China, most Brazilians do prefer a scenario in which China surpasses the US as the main economy in the world. This is very pragmatic reasoning, we believe. To the question “in your opinion, if China’s economy grew to be as large as the United States, do you think that fact would be positive or negative for the world?” Most Brazilians respond in a pro-Chinese fashion, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Opinion Towards Chinese Economic Growth.

Note: Elaborated by the authors. N=1881.

Despite rivalry and the economic effects of Chinese expansion in Brazil and Latin America, the rise of China in relation to the United States is positively viewed by the Brazilian survey respondents. One possible cause of this result is the sustained belief that Chinese growth will simultaneously imply an opportunity for exports of low value-added products and a counterweight to the historic US hegemony in the region. Foreign aid and Chinese infrastructure investments also help shape this outlook, supported by the idea that Chinese growth mitigates the degree of dependence on the US, viewed positively by countries in the region. Thus, we suggest, the degree of trust on China in global governance issues can acquire a positive trend as long as the Chinese economic presence increases, counterbalancing American dominance. In this proposition, the formation of a proto-bipolar order can progressively open space to the Chinese recognition as a legitimate global player in the region.

Empirical Findings

From the survey we know that most Brazilians see China as an untrustworthy partner. Furthermore, we know that most Brazilians prefer that China surpasses the United States economically. We believe that because the appeal of China to Brazilians is mostly economic, as Chinese economic statecraft grows, Brazilians will shift their perceptions towards a more trusting view of China. To test empirically our hypothesis, we estimated a logistic model that can be expressed as

P(TrustChina=1│x)=G(β0+β1 ChinasurpassesUSA1+…+βk controlsk)

To test the relationship between our independent and dependent variables we run four different specifications of our baseline model for robustness purposes. The first of these is a logistic regression without controls and without federal unit fixed effects. The second specification includes controls but not fixed effects. The third specification includes both controls and fixed effects. Finally, we run a multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression with controls to let slope coefficients to randomly vary across Federal Units. For the main independent variable, we considered the question we analyzed in the previous section: “In your view, if China’s economy grows to be as large as the United States’, do you think that this would be positive for the world?”, the answer to which is “yes” or “no”.

To control for the respondent’s appraisal of Chinese migrants we considered the following question: “What is your overall opinion on the Chinese people living in your country?”. The variable was originally of ordinal nature, ranging from very positive (1) to very negative (5), and we created a dummy variable which assumes the value of 1 when the opinion on the Chinese diaspora is worse than the average opinion on the other nationalities being asked in the survey (i.e. American, Bolivian, Equatorial, Paraguayan, Peruvian, Spanish, Uruguayan, Venezuelan). In this way, we ensure that what we measure is the negative opinion towards the Chinese and not towards all immigrants.

To control for perceived costs associated with an increasing exposure to trade with China in each federal unit we created a variable which measures if the person lives in a federal unit whose main exports are the main national export to China (i.e. soybeans). To create this variable, we used the information on federal units retrieved from the Brazilian Ministry of Economy. This variable was coded as a dummy variable.

The literature that uses survey data to analyze foreign policy positions typically includes controls for socioeconomic and ideological preferences at the individual level (Kertzer & Zeitzoff 2017). We used the appraisal the person made of American influence in Latin America; if the person lives (or not) in an urban center (larger than a million people); the person’s age, gender and their degree of knowledge of international issues.

Table 3: Regression Results.

| Logit | Logit | Logit | Multilevel Logit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive if China surpasses USA | 3.461*** (11.42) |

2.487*** (5.09) |

2.644*** (5.31) |

2.495*** (5.08) |

| Perception of Chinese Immigrants | 1.873*** (3.62) |

1.857*** (3.51) |

1.872*** (3.62) |

|

| Perception of Chinese Immigrants | 1.131 (0.73) |

1.513 (0.75) |

1.116 (0.59) |

|

| Urban Area | 0.865 (-0.82) |

0.957 (-0.20) |

0.867 (-0.79) |

|

| Opinion on US’ Role in Latin America | 1.081 (1.63) |

1.078 (1.52) |

1.081 (1.62) |

|

| Ideology | 0.988 (-0.44) |

0.988 (-0.41) |

0.988 (-0.43) |

|

| Income | 1.368 (1.87) |

1.353 (1.77) |

1.367 (1.86) |

|

| Degree of Information | 0.928 (-0.86) |

0.921 (-0.92) |

0.927 (-0.87) |

|

| Gender | 1.413* (2.09) |

1.435* (2.14) |

1.414* (2.09) |

|

| Age | 0.996 (-0.75) |

0.994 (-1.01) |

0.996 (-0.76) |

|

| Fed. Units’ Fixed Effects | No | No | No | No |

| Observations | 1881 | 708 | 708 | 708 |

| Pseudo R Squared | 0.058 | 0.066 | 0.083 | |

| AIC | 2312.8 | 898.3 | 906.3 | 900.3 |

Note: Odds ratios as coefficients; T statistics in parentheses. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001. Dependent variable = 1 if China is a trusting partner.

Our results show that the odds of a Brazilian trusting China is 2.5 and 3.5 (depending on the model specification), higher if the person sees as a positive outcome that China is surpassing the United States economically. Furthermore, the odds are higher (1.80 times higher) when the person has a positive image of the Chinese diaspora living in Brazil.

Trapped in Proto-Bipolarism?

The Chinese rise to the status of global power has profoundly altered the extent of US dominance in Latin America and the potential of the Brazilian claim of being a regionally prominent actor. This new global configuration reduces Brazilian options for accessing international political and economic resources. The country is trapped between the two largest economies of the world. While the systemic conditions for Brazil being among the greatest powers has become more complex, the reactions on the part of Brazilian public reflects such anxieties and dilemmas. As we have presented in this work, Brazilian attitudes reveal the mood of relations between Brazil, the United States, and China.

The rise of China has created mistrust among large parts of the world. After briefly reviewing the literature on the intentions of China and its growth, we evaluated how the Chinese rise is interpreted by the Brazilian audience. To a greater degree than economic matters, what seems to attract the attention of, and cause a general distrust in, the public are the values held by the Asian country. American influence in Brazil is still strong after all. Despite the long history of ups and downs, the United States has not disassociated itself from its position of regional leadership. High interdependence in trade and investments, as well as the wide advantage in the cultural domain, give the United States a status of the natural regional representative. No matter how much effort it makes, China still holds a position of low prestige among South American countries.

Despite its lack of legitimacy as an alternative model of power, China appeals to Brazilians as an economic superpower. This is not news (Oliveira 2010). What is new is that we find a positive association between China’s economic appeal and how trustworthy the country is perceived to be. Results suggest that Brazilians value pragmatism in relation to China, and money can win over their hearts. Despite this finding, the novelty arises when we look at the optimistic way Brazilians see Chinese growth in relation to the relative stagnation of American global economic dominance. It also means, to a certain extent, that the possible Brazilian resistance against increasingly Chinese influence in the region can be mitigated through the economic benefits of such ascension, despite the obstacles the lack of soft power could create.

In summary, Brazilians are pragmatic from an economic point of view but normatively adhere to American values. China lacks the soft power to be an alternative to the US hegemonic influence in Brazil but can strengthen its economic link with the country to win over hearts and minds.

Notes

Funding

São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), grant 2014/03831-3. Francisco Urdinez would like to thank the Millennium Nucleus for the Study of Stateness and Democracy in Latin America (RS130002), supported by the Millennium Scientific Initiative of the Ministry of Economy, Development and Tourism of Chile. Pietro Rodrigues is funded by CAPES Foundation (Ministry of Education of Brazil)

References

Acharya, A 2014, The end of American world order, John Wiley & Sons.

Bräutigam, D & Xiaoyang, T 2012, ‘Economic statecraft in China’s new overseas special economic zones: Soft power, business or resource security?’, International Affairs, vol. 88, no. 4, pp. 799–816.

Brawley, MR 2007, ‘Building Blocks or a Bric Wall? Fitting U.S. Foreign Policy to the Shifting Distribution of Power’, Asian Perspective, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 151–175.

Buzan, B & Cox, M 2013, ‘China and the us: Comparable cases of “peaceful rise”?’, Chinese Journal of International Politics, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 109–132.

Campello, D 2015, The politics of market discipline in Latin America: globalization and democracy, Cambridge University Press.

Chan, S 2007, China, the US and the Power-transition Theory: A Critique, Routledge.

Chen, D, Pu, X & Johnston, AI 2014, ‘Debating China’s Assertiveness’, International Security, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 137–159, retrieved from <http://search.ebscohost.com.ebscohostresearchdatabasestest0.han3.lib.uni.lodz.pl/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=89040177&lang=pl&site=eds-live>.

Christensen, TJ 2006, ‘Fostering Stability or Creating a Monster? The Rise of China and U.S. Policy toward East Asia’, International Security, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 81–126.

Dauvergne, P & Farias, DB 2012, ‘The Rise of Brazil as a Global Development Power’, Third World Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 903–917, retrieved from <http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=75273944&site=ehost-live>.

Drezner, DW 2011, ‘Does Obama Has a Grand Strategy? Why We Need Doctrine in Uncertain Times’, Foreign Affairs, vol. 90, no. 4, p. 59.

Ferchen, M 2011, China-Latin America relations: Long-term boon or short-term boom?,.

Gill, B & Huang, Y 2006, ‘Sources and limits of Chinese “soft power”’, Survival, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 17–36, retrieved from <http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00396330600765377>.

Glaser, CL 2015, ‘A U.S.-China Grand Bargain? The Hard Choice between Military Competition and Accommodation’, International Security, vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 137–159, retrieved from <http://search.ebscohost.com.ebscohostresearchdatabasestest0.han3.lib.uni.lodz.pl/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=89040177&lang=pl&site=eds-live>.

Harris, P 2015, ‘The imminent US strategic adjustment to China’, Chinese Journal of International Politics, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 219–250.

Huntington, SP 1999, ‘The Lonely Superpower’, Foreign Affairs, no. 35, pp. 35–49.

Hurrell, A 1992, ‘Latin America in the New World Order : A Regional Bloc of the Americas?’, International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-), vol. 68, no. 1, pp. 121–139.

Hurrell, A 2006, ‘Hegemony, Liberalism and Global Order: What Space for Would-Be Great Powers ?’, International Affairs, vol. 82, no. 1, pp. 1–19.

Ikenberry, GJ 2008, ‘The Rise of China and the Future of the West: Can the Liberal System Survive?’, Foreign Affairs, vol. 87, no. 1, pp. 23–37, retrieved from <http://0-web.ebscohost.com.pugwash.lib.warwick.ac.uk/ehost/detail?sid=16798cdf-ce93-4d8c-ac20-32fb1b58eb4c@sessionmgr104&vid=1&hid=106&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ==#%5Cnhttp://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=buh&AN=28018827&site=ehost-live>.

Ikenberry, GJ, Mastanduno, M & Wohlforth, WC 2009, ‘Unipolarity, State Behavior, and Systemic Consequences’, World Politics, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 1–27, retrieved from <http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S004388710900001X>.

Ikenberry, J 2011, ‘The Future of the Liberal World Order’, Foreign Affairs, vol. 90, no. 3, retrieved June 13, 2017, from <https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/23039408.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Abd17b78de1fcd86309f53f76894d561e>.

Kertzer, JD & Zeitzoff, T 2017, ‘A Bottom-Up Theory of Public Opinion about Foreign Policy’, American Journal of Political Science, vol. 0, no. 0, pp. 1–16.

Layne, C 2008, ‘China’s challenge to US hegemony’, Current History, vol. 107, no. 705, pp. 13–18.

Legro, JW 2007, ‘What China Will Want: The Future Intentions of a Rising Power’, Perspectives on Politics, vol. 5, no. 3, p. 515, retrieved from <http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1537592707071526>.

Loureiro, FP, Guimarães, FS & Schor, A 2015, ‘Public opinion and foreign policy in João Goulart’s Brazil (1961-1964): Coherence between national and foreign policy perceptions?’, Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, vol. 58, no. 2, pp. 98–118, retrieved June 13, 2017, from <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0034-7329201500206>.

Mares, DR & Kacowicz, AM 2015, Routledge Handbook of Latin American Security, Routledge.

Mearsheimer, JJ 2010, ‘The gathering storm: China’s challenge to US power in Asia’, Chinese Journal of International Politics, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 381–396.

Mingjiang, L., 2008. ‘China debates soft power’. The Chinese Journal of International Politics, vol. 2, no. 2, pp.287-308.

Mouron, F & Urdinez, F 2014, ‘A Comparative Analysis of Brazil’s Foreign Policy Drivers Towards the USA: Comment on Amorim Neto (2011)’, Brazilian Political Science Review, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 94–115, retrieved from <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1981-38212014000200094&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en>.

Mouron, F, Urdinez, F & Schenoni, LL 2016, ‘Sin espacio para todos : China y la competencia por el Sur’, Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals, no. 114, pp. 17–39.

Nadkarni, V & Noonan, NC 2013, Emerging powers in a comparative perspective: the political and economic rise of the BRIC countries, Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Neto, OA 2011, De Dutra a Lula: a condução e os determinantes da política externa brasileira, Elsevier Brasil.

Oliveira, HA 2010, ‘Brazil and China: A new unwritten alliance?’, Revista Brasileira de Politica Internacional, vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 88–106, retrieved from <http://ezproxy.concytec.gob.pe:2048/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselc&AN=edselc.2-52.0-79951782237&lang=es&site=eds-live>.

Onuki, J, Mouron, F & Urdinez, F 2016, ‘Latin American Perceptions of Regional Identity and Leadership in Comparative Perspective*’, Contexto Internacional, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 433–465, retrieved June 13, 2017, from <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8529.2016380100012>.

Pape, RA 2005, ‘Soft Balancing against the United States’, International Security, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 7–45, retrieved from <http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/10.1162/0162288054894607>.

Paul, T V 2005, ‘Soft balancing in the Age of U.S. Primacy’, International Security, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 46–71.

Power, TJ & Zucco, C 2012, ‘Elite Preferences in a Consolidating Democracy: The Brazilian Legislative Surveys, 1990-2009’, Latin American Politics and Society, vol. 54, no. 4, retrieved June 13, 2017, from <http://www.fgv.br/professor/cesar.zucco/files/PaperLAPS2012.pdf>.

Qingguo, J 2005, ‘Learning to Live with the Hegemon: evolution of China’s policy toward the US since the end of the Cold War’, Journal of Contemporary China, vol. 14, no. 44, pp. 395–407, retrieved from <http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10670560500115036>.Reilly, B 2013, ‘Southeast Asia: In The Shadow of China’, Journal of Democracy, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 156–164, retrieved from <http://muse.jhu.edu/content/crossref/journals/journal_of_democracy/v024/24.1.reilly.html>.

Rodrigues, PCS & Gonçalves, SD 2016, ‘Brazilian Foreign Policy and Investments in Angola’, Austral: Revista Brasileira de Estratégia e Relações Internacionais, vol. 5, no. 9, pp. 235–259.

Schweller, R 2011, ‘Emerging powers in an age of disorder’, Global Governance, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 285–297.

Schweller, RL & Pu, X 2011, ‘After Unipolarity: China’s Visions of International Order in an Era of U.S. Decline’, International Security, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 41–72, retrieved June 13, 2017, from <https://muse.jhu.edu/article/443888>.

Spektor, M 2009, Kissinger e o Brasil,.

Stuenkel, O 2015, The BRICS and the future of global order, Lexington Books.

Summers, T 2016, ‘Thinking Inside the Box: China and Global/Regional Governance’, Rising Powers Quarterly, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 23–31.

Tulchin, JS 2016, Latin America in international politics: challenging US hegemony Incorporat., Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Urdinez, F 2014, ‘The Political Economy of the Chinese Market Economy Status given by Argentina and Brazil’, CS, no. 14, pp. 47–75.

Urdinez, F, Knoerich, J & Feliú Ribeiro, P 2016, ‘Don’t Cry for me “Argenchina”: Unraveling Political Views of China through Legislative Debates in Argentina’, Journal of Chinese Political Science, retrieved June 13, 2017, from <http://download.springer.com/static/pdf/344/art%253A10.1007%252Fs11366-016-9450-y.pdf?originUrl=http%3A%2F%2Flink.springer.com%2Farticle%2F10.1007%2Fs11366-016-9450-y&token2=exp=1497393361~acl=%2Fstatic%2Fpdf%2F344%2Fart%25253A10.1007%25252Fs11366-016-945>.

Urdinez, F, Mouron, F, Schenoni, LL & de Oliveira, AJ 2016, ‘Chinese Economic Statecraft and U.S. Hegemony in Latin America: An Empirical Analysis, 2003-2014’, Latin American Politics and Society, vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 3–30.

Volgy, TJ & Imwalle, LE 1995, ‘Hegemonic and Bipolar Perspectives on the New World Order’, American Journal of Political Science, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 819–834.

Walt, SM 2005, ‘Taming American Power’, Foreign Affairs, vol. 84, no. 5, pp. 105–120.

Walt, SM 2009, ‘Alliances in a Unipolar World’, World Politics, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 86–120, retrieved from <http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0043887109000045>.

Yue, J 2008, ‘Peaceful Rise of China: Myth or Reality?’, International Politics, vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 439–456.

Zakaria, F 2008, ‘The Future of American Power: How America Can Survive the Rise of the Rest’, Foreign Affairs, vol. 89, no. 3, pp. 18–43, retrieved from <http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/66796/joseph-s-nye-jr/the-future-of-american-power%5Cnhttp://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/66796/joseph-s-nye-jr/www.foreignaffairs.com/print/66766>.

Zhao, S 2016, ‘China as a Rising Power Versus the US-led World Order’, Rising Powers Quarterly, vol. 1, no. 1, p. 13.