BRICS and Dispute Resolution

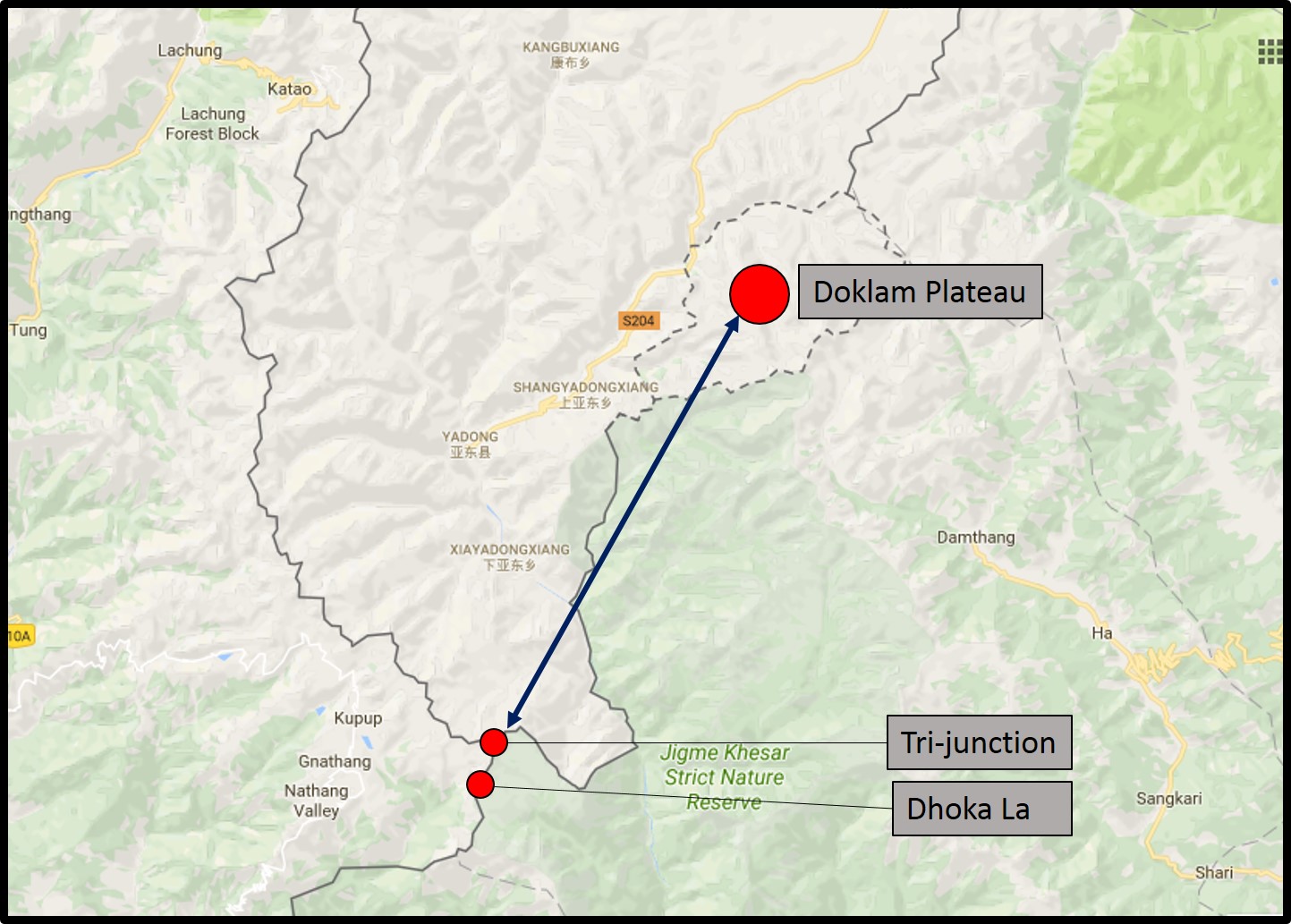

One conventional criticism of the role and future of the BRICS grouping is internal tensions and conflicts between its members. We may just have witnessed the opposite effect. The firm deadline of the next summit in Xiamen from 3–5 September exerted an external discipline on China and India to resolve a ten-week military standoff at the tri-junction with Bhutan. The narrow Doklam Plateau is a 90km strip at an altitude of over 4,000 metres that China lays claim to as belonging to Tibet but Bhutan – a de facto Indian protectorate – insists it is the rightful owner.

The tense confrontation, with the potential to provoke armed skirmishes, began on 16 June when Indian soldiers physically destroyed China’s road-building efforts in the disputed area. When PM Narendra Modi and President Xi Jinping met on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Hamburg on 7 July, they agreed that disputes should not be allowed to escalate into conflicts as both countries had much to gain from cooperation. On 28 August China and India announced a satisfactory resolution.

The standoff ended without bloodshed because it was a lose-lose proposition for both powers. The compromise solution is a limited outcome reflecting the limited stakes and high risks for the Asian giants. Modi directed the top Indian officials (National Security Adviser Ajit Doval, Foreign Secretary S. Jaishankar and Ambassador to China Vijay Gokhale) to explore pathways to an early resolution within India’s bottom line of not permitting the status quo to be changed by force.

The 1962 syndrome continues to shape Chinese and Indian actions, but with contrary memories of victorious triumphalism and humiliated nationalism. During the first several weeks of the Doklam standoff the Chinese repeatedly issued belligerent threats warning India not to forget the lessons of history on pain of a repeat.

But 2017 is not 1962 when neither had nuclear weapons and today both do. This confers an asymmetric advantage on the militarily less powerful neighbour. The risks of being caught in an out of control escalation spiral that crosses the nuclear threshold injects caution in the desire to inflict military punishment on the perceived weaker country.

The street-smart Modi is no Jawaharlal Nehru who, in acquiescing to China’s takeover of Tibet, saddled India with a permanent strategic disadvantage vis-à-vis China. He also engaged in reckless adventurism to provoke the 1962 disaster. For all his tendency to talk big and act small, in this crisis Modi held his tongue even though China issued inflammatory warnings against India’s largely measured and circumspect statements.

China has a lot more to lose economically today than in 1962. A war with a nuclear-armed neighbour would massively disrupt its development trajectory. China is at the risk of simultaneous land and sea border quarrels with many of its neighbours from Northeast Asia through the South China Sea (not to mention the growing tensions over North Korea), and the diplomatic costs quickly begin to mount to counter decades of patient diplomacy designed to emphasize China’s peaceful rise. From India’s perspective, a war with China would test its military power, defence preparedness and social cohesion; and harm its ambition of becoming a manufacturing and IT-led industrial powerhouse.

Perhaps China was trying on land the strategy of stealthy and incremental expansion, reclamation and construction of dual-purpose facilities that has served it well in the South China Sea. Bhutan alleged and India repeated charges that China attempted to create new facts on the ground by quietly constructing roads to alter the existing status quo. This is difficult to confirm independently because outsiders have little way of assessing claims and counter-claims. The legal issues in the dispute are complex and highly technical, involving treaties between the British Raj and China in 1890, pacts and understandings between Bhutan and India, the history of Bhutan–Tibet relations, and of course China’s control of Tibet.

The narrow geographical corridor is strategically vital to India for access to its own northeastern states, as well as its credibility as the de facto guarantor of Bhutan’s sovereignty. The area is less strategically vital to China than other disputed sectors in its 3,500km border with India, but perhaps China wanted to deflate uppity India’s growing military links with the US, Japan and Australia. Beijing might also have been miffed that India boycotted its recent Belt and Road Initiative summit. And it may want to signal the high costs of siding with India to smaller countries in the neighbourhood.

This was one of the most measured and mature demonstrations of professional diplomacy coming out of New Delhi in a long time. India never responded to China’s verbal provocations in kind. Officials were reported to have briefed commentators and urged them to exercise restraint in their commentary in order not to inflame the situation. On the border itself there were some incidents of scuffles, shoving and fisticuffs, but not a shot was fired by either side. Learning from the history of many previous incidents, India ramped up its military preparedness at various points along the disputed border with China, just in case. Indian troops made open preparations for the long haul through the forthcoming winter months, displaying public resolve to stay the course as long as necessary.

With on the ground stalemate, back channel efforts began to find an acceptable formula to revert to the status quo ante. The forthcoming BRICS summit helped to concentrate minds, as neither side wanted the spectacle of the grouping’s second most important leader not coming. India again showed maturity in refusing to confirm or deny public speculation of a possible boycott by Modi. His failure to attend would, as always, be more of an embarrassment to the summit host than the absent guest. His office confirmed his attendance the day after the resolution of the standoff.

The announcement of the agreement was made simultaneously in the two capitals, with tell-tale nuance and emphases in the respective wordings. China highlighted that Indian troops had pulled back and Beijing had successfully asserted its right to continue patrolling its sovereignty – which India never contested. China’s media reported the withdrawal of Indian troops but ignored China’s parallel pullbacks. Some foreign journalists too, including the China correspondent of The Australian, took China’s press release at face value to report the agreement as an Indian capitulation. A moment’s reflection, or else a phone call to the Indian embassy, would have given hint of the nuances hidden in the simultaneous announcements in Beijing and New Delhi.

The Indian statement referred to mutual disengagement and sequential troop withdrawals. Both sides agreed that if Indian troops pulled back first this offered sufficient face to China which had insisted on an unconditional Indian retreat. India agreed to this as a “goodwill gesture.” China quietly conceded to making “adjustments on the ground.” In a second statement, India confirmed that both sides had moved out “under verification” by foreign ministry and defence personnel, “expeditious disengagement of border personnel at the face-off site…was ongoing,” and Chinese troops and road-building equipment had been withdrawn. Beijing said it had stopped the road-building “for now” due to adverse “weather and other factors”.

India also briefed leaders of the major opposition parties who appreciated the gesture and supported the deal – in itself an important clue to the symmetric retreats by China and India, as one-sided capitulation would be pounced on by the opposition to lash the Modi government for a sell-out.

Hopefully next week Modi and Xi will take advantage of their meeting in Xiamen to rediscover common ground on important international issues.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence.