What’s Shaping Globalization?

Is liberalism in retreat? And with it, are the related concepts of multilateralism, openness and democracy also in disarray? Is nationalism inimical to globalization? This set of issues preoccupies discourse in many fora currently, including the Tokyo Dialogue organized by the Genron NPO earlier this month. Views there were as divided as they are more generally. But I am also struck by how much room there is for a convergence in views when a dedicated attempt is made to sort out the headlines and rhetoric from more structural trends.

Elsewhere I have argued that recent events, particularly in the US and Great Britain, cannot be interpreted as fundamental changes in public attitudes to the economy and society. Small but discernible changes in the turnout among the young and/or urban and/or more educated voters would have yielded the opposite result in the Brexit referendum. The particularities of the electoral college process in the United States translated a lead of about 3 million in the popular vote for Hillary Clinton into a victory for Donald Trump. Elections this year in several Western European countries will either undercut or re-enforce the trend of electoral victory for the forces arrayed against openness. Pending these results, we do know that the US and British votes produced outcomes that require nuance in interpretation. In China and India, governments espouse the language of nationalism while using the channels that globalization offers – trade, information and communication technologies, and finance – to integrate their countries with and anchor them to the rest of the world. Looking further afield, some countries are pre-occupied with sorting out their internal affairs (Brazil, South Africa, Turkey), some have stridently nationalist and populist governments (Hungary, Philippines, Russia) while others remain determinedly outward looking (Mexico, South-East Asia). This admittedly broad brush does not portray a global trend one way or the other.

But globalization is in threat and might even itself be considered a threat. These developments are mainly being shaped by longer term factors, not current political events.

The trade agenda ran aground during the Doha Round because the easy gains from pure tariff reduction had been achieved (with some exceptions like agriculture). What remained – the so-called behind the border issues – were of necessity tough nuts. National consensuses to enter into global or even regional agreements that brought uniformity to aspects of social and other domestic policy (like competition and investment) did not exist, and more importantly, had not been cultivated by government. Nor had governments in developed countries most vulnerable to outsourcing and the migration of low-skilled manufacturing jobs to developing countries paid attention to mitigating their impacts by, for example, strengthening social safety nets, investing in re-training and other human resource transition arrangements, and implementing meaningful innovation strategies.

In this climate, the success of the Information Technology Agreement as a next generation sectoral plurilateral deal is to be celebrated, the advent of the Trade Facilitation Agreement is promising and the demise of the Trans Pacific Partnership, with its troubling (to many) provisions on intellectual property (IP) and investor-State dispute resolution might be a source of relief. One might hope that more progress is made in the negotiations around environmental goods, and that a start is made in refreshing the global IP regime. But again, this broad brush does not portray a collapse in global cooperation on trade. Nor have the failures, such as they are, been the result of old-fashioned North-South confrontation.

Finance is another area where the blockages have been of long standing. Despite the difficulties in the Eurozone, particularly the Greek debt saga, we are no closer to a globally agreed mechanism to work through sovereign debt problems. The Financial Stability Board, while many steps in the right direction, is not treaty-based and does not have the carrots and sticks required to spot and address weaknesses in financial sectors before they become endemic. Financial sectors are vulnerable to cyber espionage and cyberattack, and central and commercial banks the world over are grappling with the implications of blockchain and other advances in technology.

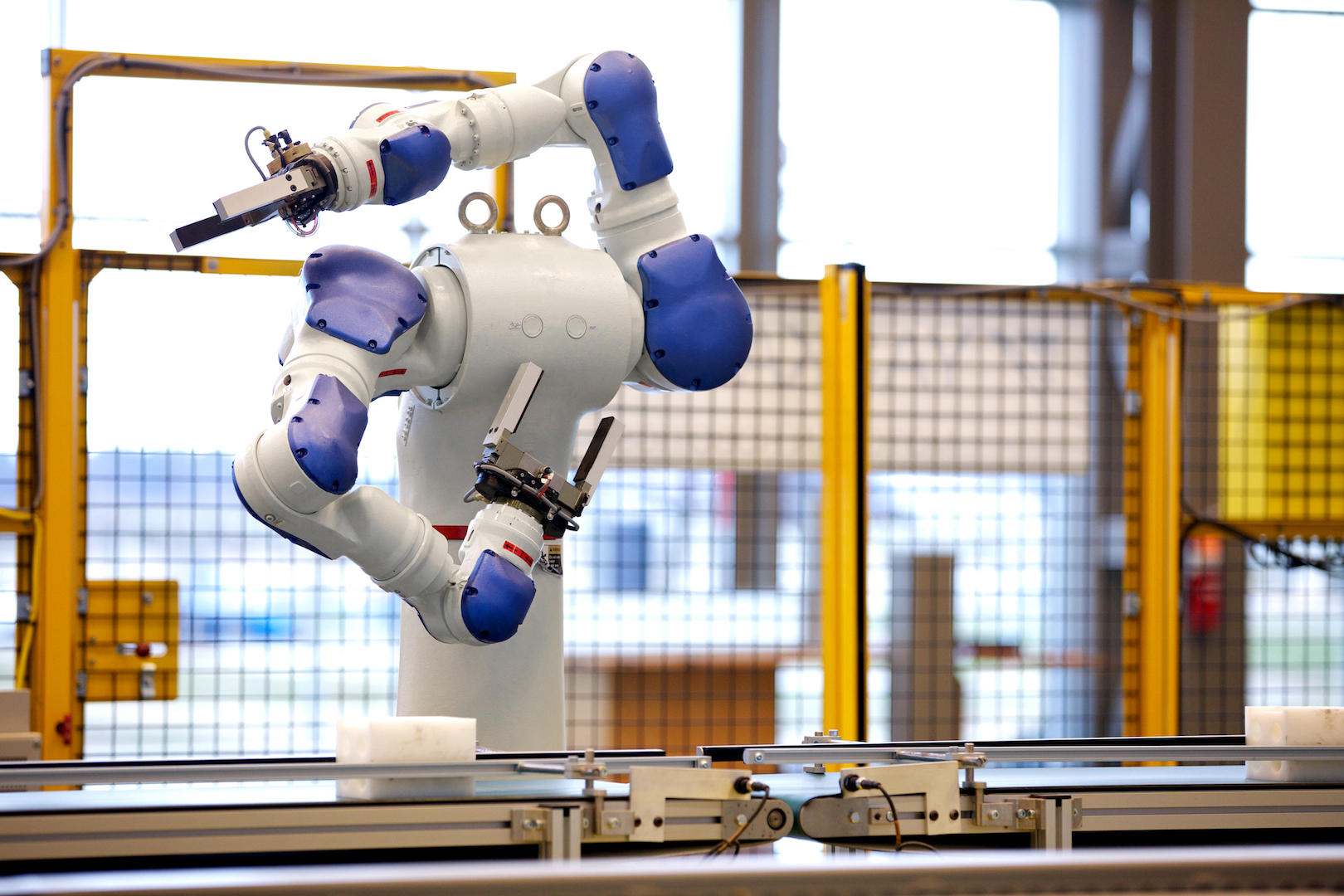

The set of changes come to be known as the fourth industrial revolution promises to upend production and trade. The latest developments in robotics mean that the route to prosperity and development that was open to the Asian “Tigers” – specialization in manufacturing goods that require low-skilled labour – is not available to late developers in (crucially) Africa and Central Asia. Once it becomes more commercially viable, 3D printing will move production closer to final consumption, not have it distant and atomized as it is currently in global supply chains.

The value of intangibles, ideas and IP is growing everywhere. Trade in ideas does not embody the same characteristics as trade in goods and services. It is characterized by high upfront costs, and very low reproduction costs. It conveys a great advantage to first movers, particularly if the technology becomes an industry standard. This also means that primacy in this matter is a global geo-political game. And economies of agglomeration are inherent in the production of IP, so existing innovation clusters have a head start over others still in the formative stage.

It does not follow that in the face of the trends described above in trade, finance and technology countries are powerless to chart their own course. On the contrary. Globalization has been uneven across sectors and across countries, and national and multilateral responses have not kept up with its speed and many facets. The G20, the self-appointed steward of economic globalization, gives emerging powers a voice at the table, more so than ever before. There is considerable room, particularly in developed and emerging countries, to strengthen social and innovation policy so that the resentment there of globalization has less grievance on which to feed. This brand of nationalism is not illiberal, and would strengthen globalization not undermine it.

The globalization of the next decade will not look like the globalization of the past three decades. Whether this is a good thing or not is an open question whose answer will not be known for some time, but whose root causes lie in factors deeper and longer than a vote or a referendum.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence.